Photo credit: Jessica Smolinksi

On Episode #10 of the Peopling the Past Podcast, we are joined by Susan Matheson, the Molly and Walter Bareiss Curator of Ancient Art at the Yale University Art Gallery and a lecturer in the Departments of Classics and the History of Art at Yale University.

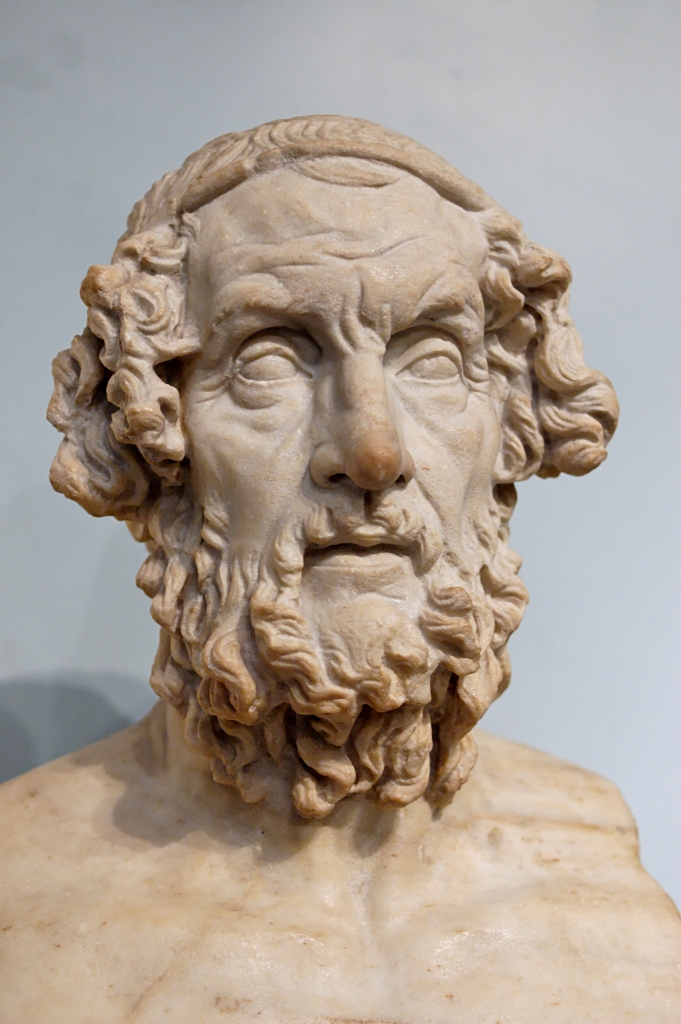

Listen in, as we discuss old age and the ways in which the elderly are depicted in ancient Greek art. Notably, Susan Matheson takes us through the varying portrayals of elderly men and women and how these differences manifest across discrete media, especially vase painting and sculpture.

Interested in learning more? Check out these related articles by Susan Matheson:

Kleiner, Diana E. E., and Susan B. Matheson, eds. I, Claudia: Women in Ancient Rome. Exhibition catalogue, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Conn., 1996

Kleiner, Diana E. E., and Susan B. Matheson, eds. I Claudia II: Women in Roman Art and Society. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press, 2000

Looking for a transcript of this episode? Click here.

Grandfathers were important figures in Greek families, as we know from ancient literary sources and inscriptions on grave stelai. This rare late archaic Greek sculpture shows an old, white-haired and partly bald man offering fruit to a small girl. Significant amounts of pigment are preserved on both figures, reminding us that most Greek sculpture was originally painted. Here close looking reveals details of the elegant textiles used to make the elder’s clothing. Such details confirm his status as the grandfather. Terracotta group sculpture in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston inv. no. 97.350, ca. 500-475 B.C.

Additional Resources Related to this Podcast

Bloomer, W. Martin, ed. A Companion to Ancient Education. Chichester, West Sussex, UK: Wiley Blackwell, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. 2015

Cokayne, Karen. Experiencing Old Age in Ancient Rome. London: Routledge, 2003

D’Ambra, Eve. Roman Women. New York: Cambridge University Press 2007

Dillon, Sheila. Ancient Greek Portrait Sculpture: Contexts, Subjects, and Style. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006

Dixon, Suzanne. The Roman Family. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992

Falkner, Thomas M., and Judith de Luce, eds. Old Age in Greek and Latin Literature. Albany, N.Y.: State University of New York Press, 1989

Fantham, Elaine, Helene Peet Foley, Natalie Boymell Kampen, Sarah B. Pomeroy, and H. A. Shapiro, Women in the Classical World: Image and Text. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994

Hart, Mary Louise, ed. The Art of Ancient Greek Theater. Exhibition catalogue Malibu, J. Paul Getty Museum at the Getty Villa, Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2010

James, Sharon L., and Sheila Dillon, eds. A Companion to Women in the Ancient World. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. 2015

Kaltsas, Nikolaos, and Alan Shapiro, eds. Worshiping Women: Ritual and Reality in Classical Athens. Exhibition catalogue New York: Alexander S. Onassis Public Benefit Foundation (USA) in collaboration with the National Archaeological Museum, Athens, 2008

Pollitt, J.J. Art in the Hellenistic Age. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986

Pomeroy, Sarah B. Families in Classical and Hellenistic Greece: Representations and Realities. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1997

Reeder, Ellen D., Pandora: Women in Classical Greece Exhibition catalogue, Baltimore: Walters Art Museum and Princeton University Press, 1995

Taplin, Oliver. Pots & Plays: Interactions between Tragedy and Greek Vase-painting of the Fourth Century B.C. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2007

Thane, Pat, ed. A History of Old Age. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2005

Woodford, Susan, The Trojan War in Ancient Art. Ithaca, N.Y. : Cornell University Press, 1993

Zanker, Paul. The Mask of Socrates: The Image of the Intellectual in Antiquity, translated by H. Alan Shapiro. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995