This post is part of a featured blog series on cultural heritage and the legacies of colonialism in the fields of ancient Mediterranean, West Asian, and North African history and archaeology, which is the topic of the fourth season of the Peopling the Past podcast.

How would you describe your area of research?

I am an archaeologist and museum researcher, with a specific interest in studying how artefacts made their way from archaeological sites into collections. This includes examining the antiquities market, provenance records, and heritage legislation. I’m also interested more generally in the relationship societies have with museums, including how public attitudes and expectations influence the nature of collections. Finally, another interest of mine is how digital technologies enable access to cultural heritage; a new research project that I’m beginning related to this is Artificial Intelligence and its threats to heritage.

What drew you to research looting and the antiquities market?

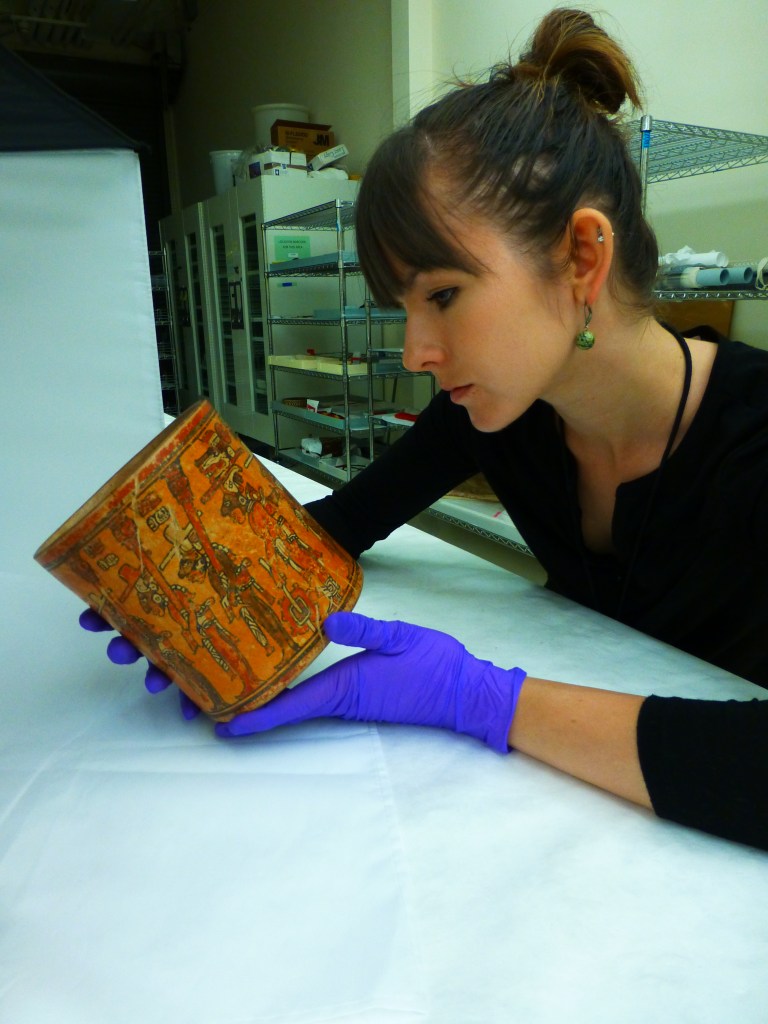

My trajectory into these topics stems from my graduate research. I was given the opportunity to study the architecture of looted ancient Maya temples in Belize for my MA research. The Maya often deposited valuable materials like ceramic and jade in temples, so looters burrow deep into these structures in search of artefacts to sell on the antiquities market. I spent close to two months working in huge looters tunnels, and became very interested in learning more about the ethical and legal issues associated with looting. For my PhD, I studied Maya dress and adornment using painted ceramics: the same kind that are looted from archaeological sites. During the process of gathering data for my dissertation, I was able to spend lots of time in museum collections and with my nose in auction catalogues. This deepened my interest in studying antiquities market practices, and my fascination definitely hasn’t waned since.

You note in a recent article that the topics of looting and antiquities trafficking remain niche and infrequently discussed. What might be the reasons for this? Are archaeologists reluctant to discuss looting or do most of us lack the training and expertise about this area? Or is it something else?

From my experience, these topics are not generally taught in great detail to archaeology students and I myself had to look to scholars outside of the discipline to learn about it. The ethical implications likely have a great deal to do with this, with organizations such as the Society for American Archaeology encouraging its members not to deal with looted materials (except to report them). I also think the division between field research and museum-based research has contributed to this problem. Many archaeologists are perhaps not as familiar with the ‘behind-the-scenes’ issues at museums, in which looted artefacts and lack of provenance are entrenched problems that need to be dealt with and can’t be avoided. Archaeologists are often very familiar with seeing one end of the trafficking chain (e.g. looting of sites), but museum-based researchers deal with the other end of it and everything that comes in between.

How should archaeologists and other heritage researchers be educating themselves on the antiquities market?

A good start is by learning about international heritage legislation, for example laws stemming from the 1970 UNESCO Convention (here in Canada for example the Cultural Property Export and Import Act was created to ratify it). Many countries had national heritage legislation pre-dating the Convention, and it is important to be aware of these laws as well. Scholars such as Patty Gerstenblith have written many articles on cultural heritage law. Another good entry point is browsing auction catalogues such as Sotheby’s or Christie’s, to get a sense of the kinds of antiquities being sold, for how much, and what information (if any) accompanies their sales. A caveat being, of course, is that much of the material on the market may not be authentic!

You’ve performed some close analysis of Maya ceramics in museum collections using techniques like optical microscopy and ultraviolet light. What further insights have these close studies revealed to you about provenance studies of museum collections (and related issues)?

The studies show the need to be realistic and open about practices that are often not spoken about, or documented, but impact the ability to study collections. Heavy-handed restorations of artefacts are commonplace, and blur the lines between authentic and inauthentic. Maya ceramics for example were often ‘touched up’ with modern paint to make them more aesthetically appealing and valuable. Unskilled and unethical restorers often work on them, creating ‘new’ interpretations of scenes and completely modifying or falsifying some of the details. Perhaps more damaging is the fact that some ceramics have no authentic elements at all, and are entirely modern fabrications. Numerous scholars have based interpretations of Maya society on these painted ceramics, without acknowledging or perhaps understanding these issues.

So while provenance research is important for understanding how an artefact may have entered a collection, equally important is hands-on research to judge whether artefacts are authentic or falsified. Basic macroscopic and microscopic investigation, and other non-destructive analyses, can go a long way to uncovering information like this (‘Real Fake’ is an interesting open access book that details additional techniques for scholars to investigate issues of authenticity in museum collections).

Building on the above question, are there any ethical ways in which scholars can use looted materials to study the past?

For me, it is ethical to study looted materials to learn about them in relation to trafficking networks that brought them into a collection. Not only do we retrieve some of the otherwise ‘lost history’ of materials, but we increase our understanding of how the antiquities market operates. If scholars study looted materials in a vacuum, divorced from their nature of acquisition, that is not only less ethical but also less helpful in advancing our fight against the illicit antiquities market. I would suggest scholars limit their research to public collections such as museums, where they are at least temporarily safe from being sold off into private collections (though even legally excavated artefacts are at risk of being auctioned, as we saw with the controversy when the St. Louis chapter of the AIA sold their collections of Egyptian and Mesoamerican artefacts). Additionally, scholars must make an effort to track down provenance paperwork and be upfront about the known legal and ethical situation surrounding the material. In short, don’t shy away from the problematic nature of working with such material but endeavour to learn more about it.

I note your co-authored discussion on the treatment of Maya heritage in the British Museum. What are some more ethical ways in which museums can deal with stolen heritage that is currently in their storage rooms or on display? The obvious answer is “give it back” but oftentimes there seem to be more complex conversations at play between institutions and stakeholders.

This is difficult to answer because museums come in all different shapes and sizes, with differing resources and knowledge bases. Those with the capacity and funding to do so are becoming much more transparent about the nature of their past acquisition practices, and how they are doing things differently to bring more voices into their spaces and address inequalities. It also takes capacity to fully understand looted materials and how to deal with them. Smaller museums will fall at the first hurdle because many lack documentation about where their collections originated, so returning isn’t even an option right now. Students and scholars can help support museums with this work by researching provenance. In an ideal world of course museums would do this work themselves, but many are struggling even to keep their doors open with growing funding cuts. Despite the challenges, museums around the world are doing the work to ensure that heritage makes its way back to communities, or are creating opportunities for communities to access their heritage (sometimes this is preferred over return). It is a shame that examples like the Parthenon Sculptures in the British Museum are given so much media attention in this regard, because it reinforces the stereotype of museums not wanting to cooperate. This type of work is sensitive, shouldn’t be rushed, and takes effort on both ends (museums and communities). With more scholars working to support museums in the process, some of that work will become easier.

Additional Resources

Brodie, Neil, Morag M. Kersel, Simon Mackenzie, Isber Sabrine, Emiline Smith, and Donna Yates. “Why There Is Still an Illicit Trade in Cultural Objects and What We Can Do About It.” Journal of Field Archaeology 47, no. 2: 117–30. 2022

Brodie, N., & Tubb, K. W., eds. Illicit antiquities : the theft of culture and the extinction of archaeology. Routledge. 2002.

Lazrus, Paula K., and Alex W. Barker, eds. All the King’s Horses: Essays on the Impact of Looting and the Illicit Antiquities Trade on Our Knowledge of the Past. Washington, D.C.: SAA Press, 2012.

Mackenzie, S. R. M., Brodie, N., Yates, D., & Tsirogiannis, C. Trafficking culture : new directions in researching the global market in illicit antiquities. Routledge. 2020.

Messenger, P. M., ed The ethics of collecting cultural property : whose culture? whose property? University of New Mexico Press. 1999.

Oosterman, Naomi, and Cara Grace Tremain. “Are Archaeologists Talking About Looting? Reviewing Archaeological and Anthropological Conference Proceedings from 1899–2019.” International Journal of Cultural Property 30, no. 4.: 361–78. 2023

Trafficking Culture: Researching the Global Traffic in Looted Cultural Objects

Tremain, Cara Grace. “Stealing Heritage in Canada.” In Art Crime in Context, edited by Naomi Oosterman and Donna Yates, 159–75. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2023.

Tremain, Cara Grace. “Taking Ancient Maya Vases off their Pedestals: A Case Study in Optical Microscopy and Ultra Violet Light Examination.” In Contextualizing Museum Collections at the Smithsonian Institution: The Relevance of Collections-Based Research in the Twenty-First Century, edited by María Martínez-Martínez, Erin L. Sears, and Lauren Sieg, 165-178. Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology Number 54. Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press, Washington, D.C. 2022

Tremain, Cara Grace and Donna Yates, eds. The Market for Mesoamerica: Reflections on the Sale of Pre-Columbian Antiquities. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2019.

Dr. Cara Tremain is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Archaeology at Simon Fraser University. She received her PhD from the University of Calgary, her MA from Trent University, and her BA from University College London. She has experience working and researching in museums in the UK, US, and Canada. She is co-editor of The Market for Mesoamerica: Reflections on the Sale of Pre-Columbian Antiquities (University Press of Florida, 2019), and has published on the topics of looting, auction house sales, forgeries, and museum collections.

Like our content? Consider donating to Peopling the Past. 100% of all proceeds support honoraria to pay the graduate students and contingent scholars who contribute to the project.

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is appreciated. Please note that we cannot provide tax receipts, as we are not a registered charity.

Your contribution is appreciated. Please note that we cannot provide tax receipts, as we are not a registered charity.

Your contribution is appreciated. Please note that we cannot provide tax receipts, as we are not a registered charity.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearly

3 thoughts on “Blog Post #103: Looting and the Antiquities Market with Cara Tremain”