In 2021, Peopling the Past ran a month-long blog series in April on human-environment relations. This year, we’re dedicating April to the (related) area of human migration in the past, and its implications for understanding how we came to be who we are through migration, and how we balance our ever-evolving understanding of human movement with senses of place, rootedness, and identity.

I study captives in small-scale societies. For almost two decades I have pursued a global study of raiding, warfare, and captive-taking in the sorts of societies that anthropologists sometimes call chiefdoms or tribes – in other words, they weren’t states. I discovered that captive-taking was extremely common in these sorts of societies, in fact, almost universal. What surprised me even more was that captives often made up a significant proportion of these societies; sometimes as much as a quarter of the population of these groups. Even more astonishing to me was that most of these captives were women and children (Figure 1). I became fascinated with this new understanding of migration in small-scale societies and began to realize how much it would transform our conceptions of the permeability of social boundaries and the nature of migrants in the past.

I first conceived of this study many years ago when I visited a small museum in the town of Yuma, Arizona. There I saw a photo of a young woman from a pioneer family who had been captured by Native Americans and lived with them for 5 years. I began to wonder what sorts of things she learned from them and what sorts of things they learned from her.

For most of my career I have been a Southwestern archaeologist studying the ancient Pueblo people of the Four-Corners region (New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, Colorado; Figure 2). One of my main interests has been in migration and I focused on when, why, and how people in this region abandoned one locality and moved to another. Archaeologists identify ancient movement primarily through changes in artifact types and styles, as well as demographic patterns. When new or unusual artifacts appear in a region, we look broadly for where they might have originated. We also look for population decline in one area and rise in another. Until recently, archaeologists haven’t recognized that there was also an entirely different and largely invisible form of migration going on with people being snatched from their homes and hustled far away with nothing more than the clothes on their back (and often even those were taken from them).

Archaeologists have known for many decades that that the appearance of new artifact types and styles, new religions, and new cultural practices were not just the result of the replacement of one cultural group with another. But our explanations for these changes are often vague and unsatisfying. We talk about cultural knowledge passing between groups through “diffusion,” “trade and exchange” or “contact.” But there had to be real people who brought in these new ideas. As I looked at the photo in the Yuma museum of the young woman captive, I wondered if people like her might have been one way in which knowledge, ideas, and cultural practices were transferred from one group to another.

There was one other reason that the study of captives intrigued me. As a child, I lived down the street from two elderly great-aunts, Donaldina Cameron and Tien Wu (Figure 3). Donaldina Cameron had been a Presbyterian missionary in San Francisco in the early 1900s and ran a home that rescued young girls who had been brought from China as domestic slaves. At some point in my childhood I learned that Tien Wu had been one of these girls. So early on I knew about enslavement of women.

Although I am an archaeologist, my study of captive-taking in prehistory used relatively little archaeological data. My primary sources of data were ethnohistoric; in other words, early historic and ethnographic accounts. I wanted to create an understanding of captives and captive-taking in prehistoric small-scale societies. Ethnohistoric accounts would allow me to reconstruct how captives were taken, how they fit in to their captor’s societies, and the effects they had on those societies (Figure 4). Through the use of analogy I could apply this new understanding of the role of captives to prehistoric societies.

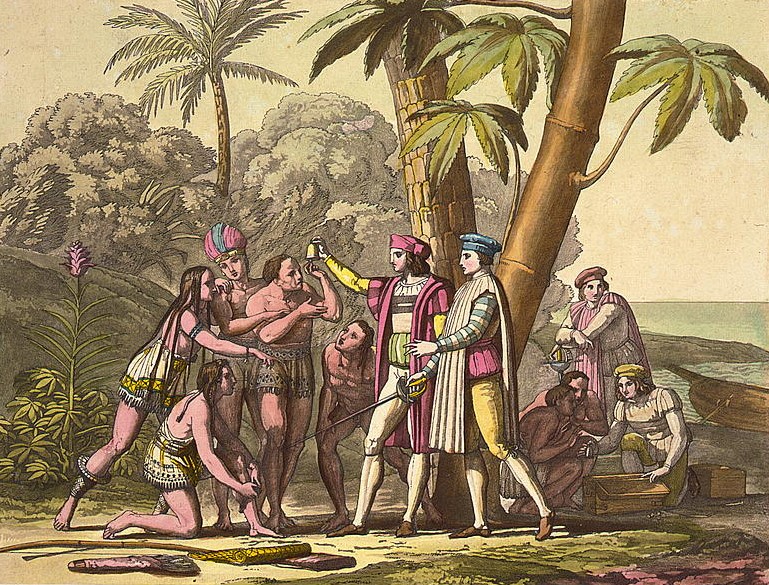

I used ethnohistoric accounts from North and South America, Africa, Europe, and Asia (especially southeastern Asia). I looked for the earliest historic accounts I could find because those should reflect the situation prior to contact; in other words that captive-taking was a common practice before European intrusion. For example, Christopher Columbus encountered captives during his earliest travels in the New World – people with scars of abuse who made signs indicating they had been taken from far away (Figure 5). I also used captive narratives, the stories of people who had escaped from captive slavery. My favorite was the first person narrative of Helena Valero who, in the 1930s at age 11, was captured by the Yanomamö of the Amazon and spent twenty years with them (Figure 6). She twice married Yanamamö men and had several children with them. Her remarkable account encapsulates so many of the experiences common to captive women in other parts of the world.

What I found in the ethnohistoric accounts astonished me. In many parts of the world, raiding and warfare were extremely common in small-scale societies with larger and more powerful groups often attacking those that were smaller and weaker, although such relationships could often reverse quickly. Women and children taken into enemy villages faced a variety of fates. Many became wives, although perhaps second or “drudge” wives, doing most of the most labor-intensive and objectionable chores in the household. Some became slaves, completely at the mercy of their owner. Some, especially very young children, were adopted and became full members of their captor’s society.

Although these were unwilling migrants, I found that they were at times able to bring new “ways of doing” to their captor’s societies, including new decorative styles, new technologies, new religious ideas, new foodways, and other sorts of cultural practices. I found that captors were eager to “mine” their captives for useful ideas and skills. I am hopeful that archaeologists interested in how cultural transmission happens will acknowledge and study captives as one method of cultural transfer.

Further Resources

Biocca, Ettore

1996[1965] Yanoáma: The Story of Helena Valero, a Girl Kidnapped by Amazonian Indians. Kodansha International, New York.

Cameron, Catherine M.

2016 Captives: How Stolen People Changed the World. University of Nebraska, Lincoln.

Donald, Leland

1997 Aboriginal Slavery on the Northwest Coast of North America. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Reséndez, Andrés.

2016 The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Robertshaw, Peter and William L. Duncan

2008 African slavery: Archaeology and decentralized societies. In Invisible citizens: Captives and their consequences, edited by Catherine M. Cameron, pp. 57-79. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City.

Raffield, B.

2019. ‘The Slave Markets of the Viking World: Comparative Perspectives on an ‘Invisible Archaeology.’ Slavery & Abolition, 40 (4), 682-705.

Santos-Granero, Fernando

2009 Vital Enemies: Slavery, Predation, and the Amerindian Political Economy of Life. University of Texas Press, Austin.

Snyder, Christina

2010 Slavery in Indian Country. The Changing Face of Captivity in Early America. Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA.

Catherine M. Cameron is professor emerita in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Colorado. She has worked in the northern part of the American Southwest, focusing especially on the Chaco and post-Chaco eras (AD 900–1300). Her research interests include prehistoric demography, the evolution of complex societies, and processes of cultural transmission. She has worked in southeastern Utah at the Bluff Great House, a Chacoan site, and in nearby Comb Wash, publishing a monograph on this research in 2009 (Chaco and After in the Northern San Juan, University of Arizona Press). She also studies captives in prehistory, especially their role in cultural transmission. She edited a volume on this topic in 2008 (Invisible Citizens: Captives and Their Consequences, University of Utah Press). Her single-authored volume on captives was published in 2016 (Captives: How Stolen People Changed the World, University of Nebraska Press).