One of Peopling the Past’s goals is to amplify the work of young and/or under-represented scholars and the amazing research that they are doing to add new perspectives to the fields of ancient history and archaeology (broadly construed). We will thus feature several blog posts throughout the year interviewing graduate students on their research topics, focusing on how they shed light on real people in the past.

What topic do you study?

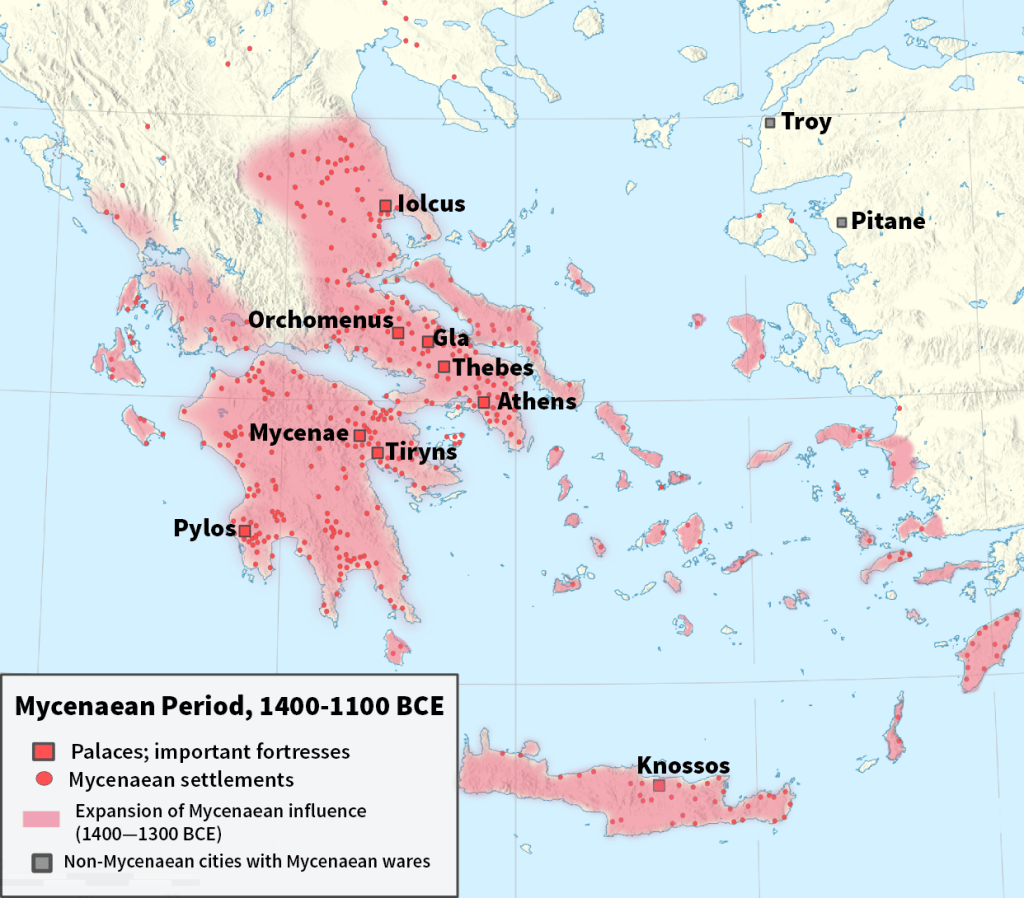

I am a PhD candidate at the University of California, Berkeley in Ancient History and Mediterranean Archaeology. My research focuses on the archaeology of religion in Bronze Age Greece and the materiality of ritual practice, with a particular focus on ritual’s shaping role in conceptions of community, identity, and ideology in ancient societies. My doctoral dissertation is an archaeological study that re-examines the structure of the religious system of the Late Bronze Age Mycenaean civilization in mainland Greece.

In particular, I challenge the traditional “official/popular” model of Mycenaean religion, which presupposes a division between state-level and popular religion. In order to challenge this accepted framework for the Mycenaean religious system and to allow for complexity within an explanatory model, I utilize techniques of data science to analyze archaeological data sets consisting of religious objects and spaces that have traditionally been associated with either official or popular religion. This investigation reveals the complexity and multivalence of Mycenaean ritual practice, demonstrating that the established binary religious framework is not corroborated by the archaeological evidence.

What sources or data do you look at?

In my dissertation, I present two primary data sets that are used to outline the structures of ritual practice across Mycenaean Greece. First, I examine ritual objects known as rhyta, vessels commonly accepted as ritual paraphernalia used for libations in the Greek Bronze Age. Rhyta first appeared on the Greek mainland at the site of Mycenae in the Late Helladic I period (c. 1600 BCE). Rhyta were brought to the mainland from the island of Crete by the early Mycenaean elites as foreign symbols of prestige, wealth, and power. By the end of the Mycenaean period, these vessels were found across the entire Mycenaean milieu and therefore have great potential to reveal patterns of diffusion of ritual practices and the development of social networks from the rise of the Mycenaean palatial period until its collapse.

I approach my analysis of Mycenaean rhyta in two ways, considering both their production and distribution. By employing exploratory data analysis it has been possible to analyze various production-related attributes of the over 400 known rhyta, such as material, shape, size, and decoration. The manipulation of this data has identified patterns of production, such as increased standardization and size, which indicate that rhyta were used both to establish and reaffirm the prominent role of elites in the social order, while also fostering social solidarity amongst all members of Mycenaean society through increased inclusion in ritual ceremonies. This interplay between cohesion and hierarchical reaffirmation denies a religious system that was siloed into distinct official and popular spheres.

In order to further interrogate this hypothesis, I utilize material network analysis to trace the diffusion of rhyta across the Greek mainland. While libation is considered to be a traditional Helladic practice that predates the Mycenaean civilization, rhyta were the earliest specialized objects designed for the purpose of pouring libations in mainland Greece. The distribution of these specialized objects therefore reflects the diffusion of institutionalized and formalized ritual practices. Using presence/absence data for rhyta at Mycenaean sites, I construct a material network that reconstructs hierarchy among Mycenaean settlements. Additionally, a diachronic analysis of the network evolution reveals a dynamic development of site hierarchy from Late Helladic I to Late Helladic IIIC (ca. 1600-1100 BCE). The results of these analyses are used to establish a model of relational ties by which power was established, maintained, and negotiated between the Mycenaean elites and lower levels of society.

Second, I employ spatial analysis of Mycenaean sacred spaces to further define communal and societal hierarchy as reflected through ritual practice. The multiple features of sacred spaces, including layout, size, accessibility, and location, are all spatial attributes that correlate with inclusive or exclusive ritual experiences. My work reveals significant overlap within a single space between inclusive and exclusive spatial features traditionally considered to be related to official and popular cults. These results signal that inclusive and exclusive behaviors were occurring simultaneously in Mycenaean sacred spaces, further indicating that Mycenaean religion did not function on two divorced levels of official and popular religion, but rather worked to build communal ties between all members of Mycenaean society.

How does this research shed light on real people in the past?

The traditional official/popular model of Mycenaean religion has forced a top-down approach in the study of Late Bronze Age ritual, creating a narrative that the religious system was wholly constructed by the state, leaving little room for consideration of the lower classes’ agency in shaping Mycenaean ritual practices and their meaning. This reassessment of the Mycenaean religious system and particularly the consideration of relational ties between community members of various levels of Mycenaean society allows for a more diversely populated reconstruction of Bronze Age society. More specifically, my study’s focus on ritual objects and sacred spaces seeks to repeople Mycenaean ritual practices by centering an individual’s tactile and sensory interaction with ritual paraphernalia and the spaces in which they are used. Reconstructing an individual’s experience in potent communal ceremonies can lead to a more dynamic understanding of societal structure and collective identity.

Elizabeth received a B.A. in History from Boston College in 2009, where she majored in History with a minor in Ancient Civilizations. In 2017, Elizabeth received her M.A. in Classics from the University of Arizona. Her Master’s thesis examined the architectural anomalies observed in the Classical temple at the sanctuary of Apollo Epikourios at Bassai in ancient Arkadia. These anomalies were considered through a comparison with the temple’s Archaic predecessor and were explored within the context of the ongoing Messenian Wars and the resulting development of the identity of the Arkadians as mercenaries. Elizabeth has surveyed and excavated both prehistoric and historic sites in the Great Basin region of the United States and has most recently excavated at the Mt. Lykaion Excavation and Survey project in Greece. Elizabeth’s research interests lie in the study of religious space and interregional connections at Greek sanctuaries, especially in the Bronze Age. She interested in questions concerning the ways in which topography and landscape, including factors of land-use and resource availability, affect the location of sanctuaries and the identity of worshippers.

lizabeth Keyser’s research offers a compelling reassessment of religious practices in Mycenaean Greece.y analyzing ritual objects like rhyta and employing data science techniques, she challenges traditional models, revealing a more nuanced understanding of ancient religious systems.er work exemplifies the innovative approaches that continue to enrich the field of ancient history and archaeology.

LikeLike