One of Peopling the Past’s goals is to amplify the work of young and/or under-represented scholars and the amazing research that they are doing to add new perspectives to the fields of ancient history and archaeology (broadly construed). We will thus feature several blog posts throughout the year interviewing graduate students on their research topics, focusing on how they shed light on real people in the past.

What topic do you study?

My research focuses on the ways that the people of Greek antiquity used mythology to articulate and express a sense of their own ethnicity and how network theory can be used to understand this phenomenon. The concept of ethnicity is complex and scholars have been struggling to define it for about a century. My understanding of the concept is expansive. I believe that ethnicity can best be described as a loose sense of kinship among a large group of people. It is about expanding some of the feelings of trust and familiarity normally shared between members of a family over a wider range of people. It is not about actual biological relatedness, but rather a sense that members of your ethnicity are somehow your family regardless of how closely you actually are related.

As a social construct, ethnicity is also susceptible to change. Changing historical circumstances can influence the ways people see themselves and their relationships to those around them. This does not, however, diminish the significance of ethnicity or negate its validity as a source of group cohesion. As such a universal human phenomenon, it clearly fulfills a fundamental need for belonging and support. It does mean that the ways ethnicity changes in response to historical circumstances can be studied and understood.

With this understanding of ethnicity, the genealogies of the characters of Greek mythology become articulations of ancient Greek ethnicity at levels ranging from the global (i.e. Greeks, Persians, and other large-scale groups) to the settlement-specific (Athenian, Spartan, etc.). Many mythic characters were believed to be the eponymous founders of tribes, settlements, and entire nations. These characters were often framed as the ancestors, either real or metaphorical, of the people who constituted these groups. They were believed to be interrelated and authors from throughout Greek antiquity expounded at length on their dense familial connections in both poetry and prose. My research is about showing that when these genealogies of mythic characters are expressed as networks, they become powerful tools for the study of Greek ethnicity at all levels. Thus, mythic genealogical networks become one more source of evidence for the study of ancient Greek history.

What sources or data do you look at?

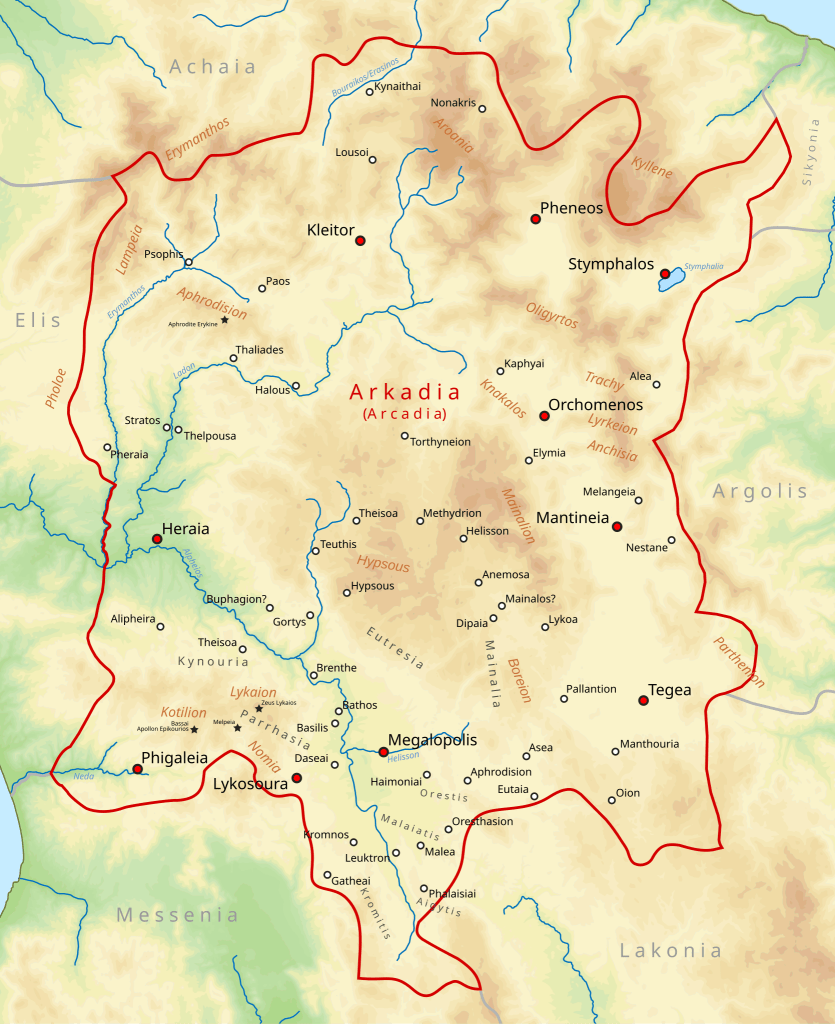

My data comes from the mythographic texts of Greek literature, or at least from texts with a prominent mythographic component to them. My most important case study is a text called Pausanias’ Description of Greece (Periegesis Hellados), which was a travel guide for mainland Greece from the second century CE that contained a lot of mythology. I focus on this text’s description of the region of Arcadia in the central Peloponnesus. As a relatively isolated region with a unique history, Arcadia provides a good case study for my theories and allows me to develop a step-by-step methodology that can be applied to other texts and other regions.

To use this text as a source of data, I extract all the relationships, familial and otherwise, between mythological characters in the text and create a network in which mythic characters serve as the network nodes and the relationships between them serve as their connections. I then use network theory to analyze this network of relationships. By comparing it to the historical record of Arcadia, I get a strong sense of the ways ethnicity developed in ancient Arcadia at many levels and the ways that mythology was used to justify and articulate people’s beliefs in their own ethnicity.

In the future, I hope to compare these mythic genealogical networks to other networks that express connections between settlements and groups of people in ancient Greece. These might include similarity networks that connect settlements with similar archaeological records, networks of diplomatic connections, and road networks. In this way, I will be able to see how the connections articulated by mythology compare to other ways that groups of people were connected to each other in antiquity.

How does this research shed light on real people in the past?

Recently, instrumentalist views of ethnicity, particularly ancient ethnicity, have been heavily criticized. Ethnic instrumentalism argues that ethnicity is more of a social construct than something based on biological relatedness between people. As a social construct, it is subject to change and can be used as an instrument to address people’s interests. There is an assumption that by claiming that ethnicity can change depending on historical circumstances, we diminish its importance. There is also an assumption that changes in ethnicity must be the result of scheming political leaders manipulating people’s sense of their own identity. My research attempts to show that the formation of ethnicity or ethnogenesis was something in which all people took part. Since many mythic characters were associated with locations and groupings of people that were central to everyday life in ancient Greece, I aim to show that the ethnic identities articulated by Greek mythic genealogies were an essential part of real people’s lived experiences.

Ben Winnick is a candidate for a PhD at the University of British Columbia (https://amne.ubc.ca/profile/benjamin-winnick/). He specializes in Greek mythology and network theory. He received his BA in 2012 from the University of Pennsylvania and his MA in 2015 from the University of Arizona.

One thought on “Blog Post #96: Graduate Student Feature with Benjamin Winnick”