This post is part of a featured blog series on cultural heritage and the legacies of colonialism in the fields of ancient Mediterranean, West Asian, and North African history and archaeology, which is the topic of the fourth season of the Peopling the Past podcast.

We’re interested in learning first about your background in maritime archaeology and how that translated into projects documenting threatened heritage. What skillsets do you bring to bear on these types of projects?

My engagement with maritime and coastal archaeology began by chance. While working on my PhD on landscape archaeology in Cyprus, a colleague from the University of Edinburgh, David Sewell, pointed out a rapidly eroding coastal archaeological site at the mouth of the Vasilikos River (Tochni Lakkia). Since 2012, we have revisited Tochni numerous times, documenting the exposed scarp initially using traditional methods—such as photographs and drawings—and later employing more advanced techniques like Terrestrial Laser Scanning (TLS) and photogrammetry.

As the project evolved, its geographical scope expanded to encompass other areas of the island also affected by erosion. At the time, these locales were mainly documented in relation to infrastructure development. However, it quickly became apparent that important archaeological features—crucial for reconstructing narratives about the past—were disappearing faster than they could be documented.

Working with threatened coastal heritage requires advanced GIS skills for tasks such as acquiring, correcting, geo-referencing, and comparing aerial and satellite imagery. The use of these technologies, coupled with the realisation that halting or significantly mitigating erosion is impossible, led me to explore the development of low-cost, sustainable workflows for heritage documentation. These workflows are designed to be adaptable in environments with limited resources for heritage monitoring.

How was the GAZAMAP project conceived?

In 2019, I was hired by the Maritime Endangered Archaeology project (MarEA) project at the University of Southampton, where I contributed to the first and largest database of endangered maritime archaeology in the Middle East and North Africa. As part of this project, I collaboratively developed a workflow for monitoring and assessing the impact of tropical cyclones in the Arabian Peninsula.

At the same time, I sought to test the workflows developed for Cyprus in other Mediterranean contexts affected by severe coastal erosion (especially the Levantine coast), particularly in regions facing significant financial constraints. The Gaza Strip emerged as an obvious choice. The area is home to a high concentration of important archaeological sites, many of which—especially in the southern half—have been eroding at an unprecedented rate since the construction of the Aswan Dam.

Moreover, access to funding, expertise, and maritime technologies in Gaza is extremely limited. While some environmental impact assessments have been carried out by coastal engineers, the necessary tools for coastal heritage monitoring are available, though dispersed across various sectors.

During this period, Yasmeen and I met in London to discuss the feasibility of a project focusing on documenting and monitoring maritime heritage in Gaza. We also emphasized the importance of conducting the project in an inclusive and equitable manner, ensuring fair pay for student trainees involved in the work and mutually beneficial relations between experts and non-experts.

What are the goals of the GAZAMAP project and how have they changed since October 2023?

The original goals of the project were to establish a network of professionals whose complementary skills could support a coastal survey aligned with the academic standards of the broader region. A key element of the project was the use of open-access technologies for heritage documentation (KoboCollect and Mapillary), the development of an interdisciplinary team (comprising archaeologists, GIS specialists, and media professionals), and skill-building, with a particular focus on archaeology students—who have extremely limited opportunities for fieldwork participation.

After completing two seasons of GAZAMAP, we were awarded a grant to deliver specialised training on underwater heritage documentation at a dedicated centre in Egypt, in collaboration with Dr Julia Nikolaus from Ulster University. Unfortunately, this coincided with the outbreak of war in Gaza, which led to the deaths of three members of our team and displaced the rest. As a result, training could only be delivered to those who had managed to flee to Egypt, as well as to some colleagues from the West Bank. Additional training was provided remotely to Gazan students, focusing on developing their skills in photo and media processing. We hope that, once their safety is assured, they will be able to resume monitoring coastal archaeological sites.

What are the major challenges of cultural heritage documentation and protection within communities impacted by conflict?

During and after conflicts, there is usually an increased influx of foreign funding aimed at documenting endangered heritage. While this work is both urgent and crucial, given the scale and intensity of heritage destruction in Gaza, it is equally important to avoid putting heritage professionals’ lives at risk during the monitoring and documentation phase. Furthermore, these initiatives should be led by individuals on the ground who have a firsthand understanding of the documentation needs, as well as the social value of heritage sites. This is not always straightforward, particularly when the administrative bodies controlling or managing access to these sites are not internationally recognised.

In addition, heritage documentation should be considered in the context of broader efforts to manage the vast amounts of rubble resulting from the conflict. In Gaza, it is highly probable that building rubble will end up in the sea, potentially covering submerged archaeological remains. A balance must be struck between heritage work, development, and humanitarian efforts, ensuring that the needs of various stakeholders—especially local communities who have endured immense suffering over the past 16 months—are addressed.

The combination of student training and the open-source technology to document the maritime and terrestrial heritage of Gaza is really innovative and significant. How can GAZAMAP be a model for other scenarios around the world where cultural heritage is threatened, particularly areas that often remain inaccessible?

Gaza is arguably one of the most challenging environments for maritime heritage documentation. Maritime sites are deteriorating at a very rapid rate, expertise is limited, and access to vital materials and equipment—such as snorkelling masks—is heavily restricted. Additionally, there is an unprecedented level of sea pollution caused by the blockade and the destruction of sanitation and other critical infrastructure over the past year.

The success of the project, measured by the remapping sites and the identification of vulnerable features, is closely tied to the hard work, resilience and innovation of Gazan students. They had to navigate these difficult conditions, compounded by electricity, internet, and transportation restrictions. If such progress can be achieved in this context, it is hard to see why similar approaches could not be applied in other parts of the world that are politically more stable but equally resource-limited.

Your recent joint-authored piece in American Anthropologist raised the important question of who heritage documentation is really for, given that archaeology and heritage preservation are always political endeavours. How do we ensure that this documentation remains for the people of Gaza, the stakeholders of this heritage?

There are significant efforts to monitor and document Gaza’s heritage. However, for various reasons, these efforts often refrain from addressing in detail the humanitarian impact of destruction on heritage professionals or the political dimensions of heritage work. There is a tendency to equate political neutrality with objectivity, but in my opinion, this is not possible to uphold, particularly in the context of Gaza. The involvement of different governments in the conflict, along with the positions taken by certain universities and professional organisations—whether through silence or active silencing—indicates that this is a political issue. This is also reflected in the use of anonymity to protect the identity of my co-author and the sponsors who have generously provided scholarships to some Gazan archaeology students.

Heritage professionals are often asked to provide lists of “important” sites without clarifying the criteria used for this classification—whether they are considered archaeologically, historically, architecturally, or socially important. Ideally, these lists should incorporate ethnographic studies that consider the social value of archaeological sites.

For the documentation to truly serve the people of Gaza, their voices must be prioritised. Employment opportunities for Gazan individuals should be a central focus in future heritage conservation and regeneration projects initiated by international experts. In addition to the heritage work itself, there must be advocacy for facilitating future training for those individuals who are currently unable to leave Gaza.

Attribution

GAZAMAP is funded by the Honor Frost Foundation and the Faculty of Arts and Humanities, University of Southampton. Subsequent training in underwater archaeology is funded by the Cultural Protection Fund, British Council.

Bibliography

Andreou, G.M, R. Opitz, S.W. Manning, K.D. Fisher, D.A. Sewell, A. Georgiou and T. Urban. 2017.Integrated Methods for Understanding and Monitoring the Loss of Coastal Archaeological Sites: The Case of Tochni-Lakkia, South-Central Cyprus.” Journal of Archaeological Science, Reports 12: 197–208. doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2017.01.025.

Andreou, G.M. 2018. Monitoring the impact of coastal erosion on archaeological sites: the Cyprus Ancient Shoreline Project. Antiquity. 2018;92(361):e4. doi:10.15184/aqy.2018.1

Andreou, G.M., M. Fradley, L. Blue and C. Breen 2022. Establishing a baseline for the study of maritime cultural heritage in the Gaza Strip. Palestine Exploration Quarterly, 156(1), 4–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/00310328.2022.2037923

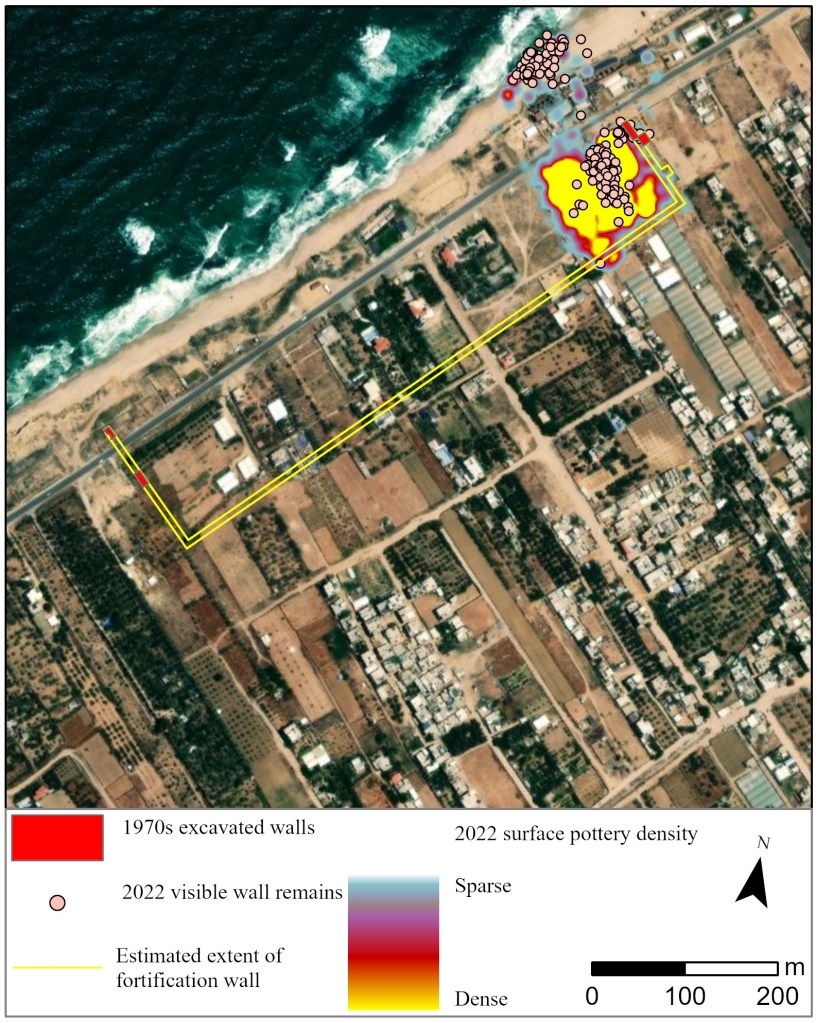

Andreou, G.M., Y. Elkhoudary and A. Hassouna 2024. New investigations in Gaza’s heritage landscapes: the Gaza Maritime Archaeology Project (GAZAMAP). Antiquity. 2024;98(400):e24. doi:10.15184/aqy.2024.68

Breen, C., L. Blue, G.M., C. El Safadi, H.O. Huigens, J. Nikolaus, R. Ortiz-Vazquez, N. Ray, A. Smith, S. Tews and K. Westley 2022. Documenting, protecting and managing endangered maritime cultural heritage in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. Journal of Maritime Archaeology 17, 341–352. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11457-022-09338-z

Bios

Yasmeen Elkhoudary – I am researcher and communications expert specialising in Gaza’s heritage and history. As the daughter of Jawdat Khoudary, founder of Almathaf—the first museum of archaeology in Gaza—I have a deep-rooted passion for preserving the region’s rich cultural legacy. Since 2022, I have led the fieldwork for the Gaza Maritime Archaeology Project (GAZAMAP), serving as a vital link between Gaza and the UK. Beyond my dedication to studying and safeguarding Gaza’s archaeology, I currently work in Project Management at Stronger Stories.

Georgia Andreou – I am a Lecturer in Archaeology & Sustainability at the University of Southampton. My research focuses on coastal societies of the Eastern Mediterranean during the 2nd and 1st millennia BCE, including surveys and excavations on the island of Cyprus. Since 2022 I have directed the Gaza Maritime Archaeology Project (GAZAMAP), documenting actively deteriorating coastal sites primarily in Deir el-Balah. My most recent project, Critical Heritage Under Water, examines the political dimensions of the study and management of underwater heritage in the Eastern Mediterranean.

Like our content? Consider donating to Peopling the Past. 100% of all proceeds support honoraria to pay the graduate students and contingent scholars who contribute to the project.

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is appreciated. Please note that we cannot provide tax receipts, as we are not a registered charity.

Your contribution is appreciated. Please note that we cannot provide tax receipts, as we are not a registered charity.

Your contribution is appreciated. Please note that we cannot provide tax receipts, as we are not a registered charity.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearly

6 thoughts on “Blog Post #105: The Gaza Maritime Archaeology Project (GAZAMAP)”