One of Peopling the Past’s goals is to amplify the work of young and/or under-represented scholars and the amazing research that they are doing to add new perspectives to the fields of ancient history and archaeology (broadly construed). We will thus feature several blog posts throughout the year interviewing graduate students on their research topics, focusing on how they shed light on real people in the past.

What topic are you aiming to pursue in your PhD research?

At the moment, I am working on a dissertation prospectus focused on religious kinship, affect, and belonging in Ptolemaic Egypt. I’m broadly interested in how marginalized peoples located themselves within colonial societies and the ways in which religion helped mediate forms of belonging. Ptolemaic Egypt presents a particularly fascinating social context because the Ptolemies, unlike their Roman successors, did not enact policies that sought to segment its society directly along cultural, ethnic, or linguistic lines; rather, the Ptolemies portrayed themselves as equal parts Greek basileis and Egyptian pharaohs and allowed for a considerable degree of social fluidity within the population as well.

For example, the prevalence of double onomastics from this period seems to indicate that many people had both a Greek and an Egyptian name and would use one or the other based on the particular situation at hand (Clarysse 1985). However, the Ptolemies did impose economic regulations that separated groups from one another based on factors such as taxation, occupation, and conditions of land-holding—which ultimately may have created broad divisions between an elite class of Greek settler colonists and the non-elite, largely indigenous Egyptian population at the same time that it enabled certain Egyptians and their families to align themselves more closely with Greek imperial power by holding administrative and temple offices.

In this complex world where categories like ethnicity, citizenship, and class cannot fully capture the nuanced ways in which people could and likely did locate themselves socially, I find kinship and belonging to be much more productive frameworks of analysis. In particular, I am interested in the role that religion—both through the formal institution of the Egyptian temple and in the more ephemeral and localized instantiations of private/domestic or cult worship—played to help foster lines of kinship that brought people and communities together. I also hope to utilize affect theory in my work, not simply as proxy for emotion, but as a method by which to explore the possible forms and meanings of embodiment and presence that extend beyond the realm of the discursive and can accommodate kinship not just between human beings, but also non-human animals and perhaps even supernatural deities.

What sources or data are you hoping to use?

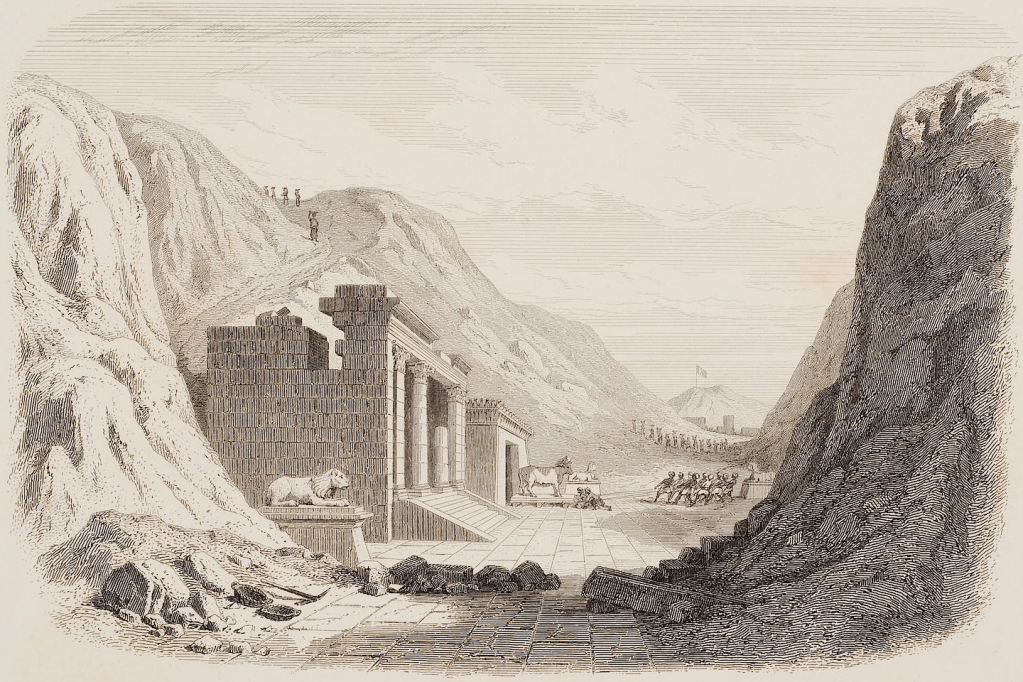

My main source of evidence is the vast corpus of documentary papyri from Egypt, as it not only provides a window for scholars into the textures of everyday life but also outlines the relationships which drove many of the activities described in these texts. Legal documents, for example, can illuminate an individual’s or family’s social networks, as people almost always entered into agreements or disputes with those whom they personally knew. I’m especially interested in the dossier of a certain Ptolemaios, the son of Glaukias, who appeared to claim some sort of religious asylum by seeking refuge at the Sarapieion at Saqqara in Memphis during the second century BCE. This collection of personal notes and letters offers a rich and colorful view into the community at the Sarapieion and traces the contours of relationships that Ptolemaios maintained during his time at the temple. Ptolemaios proves to be a particularly fascinating case study because the terms of his religious asylum appear to have confined him to the Sarapieion, yet he was nevertheless able to broker deals with parties outside of the temple, including members of the Greek administration, in order to achieve various goals for himself and on the behalf of those around him.

Another significant data set for my research is the documentary evidence from religious associations. The majority of these documents outline the specific rules and regulations of the associations but nevertheless can also paint a surprisingly vivid picture of what may have been at stake for those who joined such a group. For example, one papyrus states that for “the man among us who dies outside the village, we will equip ten men from the association and they will recover him” (P. Cair. II 30605, trans. Monson). I read this rule not only as a statement of the expectations surrounding and benefits provided by membership in an association, but also an indication of the values that members shared regarding the importance of being buried in one’s home village and, perhaps, having deceased kin close by for those who were still alive. I’m particularly interested in the way that these religious associations may have provided avenues for kinship from the perspective of affect rather than that of transaction costs or trust networks, which remains the dominant scholarly understanding of why people may have participated in such groups (Monson 2006).

How does this research shed light on real people in the past?

One of my biggest takeaways from my preliminary exams was the realization that much of the scholarship on Greco-Roman Egypt—and in fact, the ancient Mediterranean world broadly speaking—was focused on thematic questions and categories rather than the unique and particular lived experiences of the individuals who appear in our archives. The Sarapieion dossier I mentioned above has been repeatedly cited in works on ethnicity in the Ptolemaic period due to a particular line in a draft of a bureaucratic petition which claims that Ptolemaios was physically assaulted “because [he was] Greek” (UPZ I 7). However, very few studies provide the full picture behind this statement: that Ptolemaios was writing an appeal to a Greek bureaucrat and could have played up his Greekness in order to make a stronger case, and that his roommate Harmais, whom most scholars believe to have been Egyptian, was also a victim of the attack. Given these considerations, this one single line becomes even less of an ideal statement concerning the broad question of ethnicity in Ptolemaic society.

Likewise, scholars have been especially focused on understanding the terms and conditions of Ptolemaios’ religious asylum at the Sarapieion despite an unhelpful lack of information provided in his documents; rather than working with the information present in the Sarapieion dossier, scholars have had to turn to other instances of religious asylum at temples in Egypt and the ancient Mediterranean as comparanda. As much as I too would like to know why and how exactly Ptolemaios was staying at the temple, I think it’s equally—or perhaps more—important that we as scholars acknowledge that his life prior to his time at the temple was not particularly meaningful to him, and that such information does not appear in his documents for a reason. As ancient historians, we often have no choice but to mine specific dossiers and archives for answers to our broader questions about ancient societies, but I believe that we should also see our historical subjects for the uniquely contingent individuals that they were.

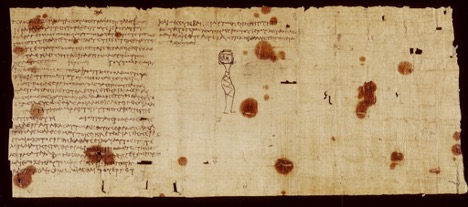

In his critical book Provincializing Europe (2001), Dipesh Chakrabarty argues for the importance of what he terms “History 2”, or “a category charged with the function of constantly interrupting the totalizing thrusts of History 1,” where “History 1” represents the universal histories that often form the backbone of dominant historical narratives (63). To me, documentary papyri hold some of the richest potential for the writing of Histories 2 if we take a step back from the usual questions we ask of these documents—about tax rates, the pricing of goods, the inner workings of legal systems—and instead see them as microhistorical snapshots from the lives of people who got into fights with their neighbors, wrote home to their parents, or became so annoyed with delayed payments from their employer that they decided to file a complaint about it. As frustrating as it can be to not find the data that we want in our archives, I think it’s also an important reminder to historians that people in the past had minds and lives of their own that are under no obligation to address the questions and concerns that we might have today. To that end, I think it’s fitting to end this post with my favorite part of Ptolemaios’ dossier: a papyrus containing the only extant Greek version of the Dream of Nectanebo that abruptly cuts off just as the story starts to get good—and instead inexplicably finishes with the drawing of a strange little person whose face is the same upside down as it is right side up.

Bibliography and Further Reading

Chakrabarty, Dipesh. Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000.

Clarysse, Willy. “Greeks and Egyptians in the Ptolemaic Army and Administration.” Aegyptus 65 (1985): 57–66.

Gorre, Gilles. “A Religious Continuity between the Dynastic and Ptolemaic Periods? Self-Representation and Identity of Egyptian Priests in the Ptolemaic Period (332–30 BCE).” In Shifting Social Imaginaries in the Hellenistic Period: Narration, edited by Eftychia Stavrianopoulou, 99–114. Leiden: Brill, 2013.

hooks, bell. Belonging: A Culture of Place. New York: Routledge, 2008.

McCoskey, Denise Eileen. “Race Before ‘Whiteness’: Studying Identity in Ptolemaic Egypt.” Critical Sociology 28 (2002): 13–39.

Monson, Andrew. “The Ethics and Economics of Ptolemaic Religious Associations.” Ancient Society 36 (2006): 221–38.

Riggs, Damien W., and Elizabeth Peel. Critical Kinship Studies. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2016.

Schaefer, Donovan O. Religious Affects: Animality, Evolution, and Power. Durham: Duke University Press, 2015.

Thompson, Dorothy J. Memphis under the Ptolemies. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012.

Dora Gao is a PhD candidate in the Interdepartmental Program in Ancient History (IPAH) at the University of Michigan and received their MA from the Ancient Culture, Religion, and Ethnicity (ACRE) program at the University of British Columbia. They work on Egyptian religion during the Greco-Roman period as well as the experiences of marginalized people under colonial hierarchies, and their dissertation focuses on religious kinship and belonging in Ptolemaic Egypt. They are also broadly interested in diasporas, bilingualism, and archive theory—and in another life, they might have written their dissertation on Homer’s Iliad. When not writing, teaching, or squinting their way through Demotic papyri, they spend their time hiking with their dog Zeke, cross-country skiing, and playing the cello.