Peopling the Past brings you an ongoing blog series, “Unknown Peoples”, featuring researchers who investigate understudied and/or marginalized peoples in the past.

Phoenician and Punic influences were long overlooked in research around the Roman Empire. Yet recently scholars have reinvestigated the contributions of Phoenician and Punic peoples towards the development of spaces that later came under Roman control. I work specifically on Punic presence in the Western Mediterranean islands of Sardinia, Malta and Sicily. My research focuses on the archaeological remains of temples, religious inscriptions, and votive objects within the context of their broader cityscapes to ask how religious practices and productions shift for Punic peoples following their absorption into the Roman Empire.

Who are the Punic People and how did they enter the Roman Empire?

When speaking about the history and archaeology of Punic Peoples, many assume the conversation will turn toward North Africa, and for good reason. The ancestors of the Punic people, the Phoenicians, are popularly known as the great seafarers of the ancient world. During the 9th and 8th Centuries BCE, they set up hundreds of colonies across the Mediterranean, each of which adapted to the local landscapes and influences in different ways. While most of these colonies trace their heritage back to Tyre and Sidon in the Levant, there is no evidence of centralized government for them. However, shared traditions and material culture show that trade connections were maintained between the colonies.

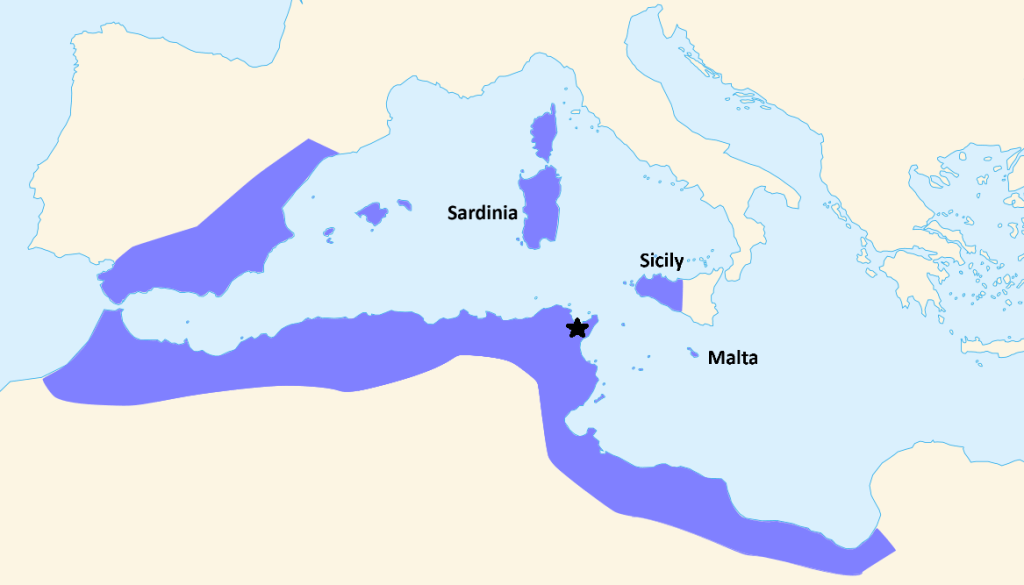

Following the fall of Tyre in the 6th Century BCE, the Phoenician colonies in the west began to realign their maritime trade networks. At this time, Carthage, in modern-day Tunisia, rose in power, successfully asserting a measure of control over many of the Phoenician colonies in the Western Mediterranean. At its maximum, Carthaginian control stretched from southern Spain in the northwest, across North Africa to the borders of Egypt and included the islands I have chosen to research: Sardinia, Malta, and parts of Sicily. Evidence for this power shift is shown through documents like the 509 BCE treaty with Rome that established Carthaginian economic and maritime control over Sardinia and cities in eastern Sicily.

We also see realignments in fashionable material culture and religious practice, reflecting the increased Carthaginian influence on trade trends and religious expression. Thus, the term Punic typically refers to those areas that were controlled and culturally influenced by Carthage. Yet the growth of the Roman Republic brought another shift in power to the region, culminating in the Punic Wars. During these wars, much of the former Punic territory came under Roman control. Though the exact dates vary based on individual victories for each side, the Punic areas in the islands of Sardinia, Malta and Sicily were fully integrated into the Roman Empire by the end of the Second Punic War in 201 BCE.

What Marks Punic Identity in the Western Mediterranean Islands?

This is one of the biggest questions for my research, as it is for others working with Punic Archaeology. The question is such a difficult one because it is evident from early on in the lifecycle of Punic colonies that a variety of cultural influences are flowing through the communities, not just the Carthaginian influences as mentioned above. Instead, in many of the Punic island sites, regular contact and intermingling with the native populations of these islands had a notable effect on the material culture brought in through trade across the Mediterranean as well as the objects produced locally. We add to that the frequent contact with Greek colonies and Italian materials for the populations of Malta, Sardinia and Sicily, and the material culture ends up looking quite cosmopolitan, representing a variety of locations and aesthetics. Malta, for example, shows evidence that adherents to local temples were bilingual, inscribing temple dedications with both Punic and Greek scripts. In some areas, these demonstrations of layered Punic identities continued for over two centuries following Rome’s absorption of the regions, despite the reorganization of power dynamics and trade. Thus, a research goal is to see how Punic elements were adapted under Rome and how people with multicultural identities may have presented themselves under an ancient empire.

Maltese coinage provides a good example of this layered identity expression under the Roman Empire. Almost immediately after the addition of Malta into the Roman Empire, 218 BCE, Maltese officials first began minting coins on the island. The early versions of these coins featured Punic script and iconography representing Egyptian and Punic gods. In later periods, they began transitioning to Hellenized and then Latin iconography and scripts until production on the island was stopped in the Roman imperial period. This example shows how the people in Malta continued their expressions of Punic identity into the period of Roman control. Moreover, the emphasis on Punic identity expression in coinage may indicate a reevaluation of what it meant to be Punic, and perhaps an intensification in the community’s desire to express that identity after coming under Roman power, as the production of the coins itself was a direct result of Malta’s absorption into the Roman Empire.

As seen with the coins, many scholars look for evidence of Punic language or script and religious iconography that was popularized during the period of Carthaginian control. I add trends in religious practice to these markers, looking closely at what architectural elements are maintained or reused from earlier Punic phases at religious sites, alongside how they are used. These questions, when applied to Punic Roman sites rich in material and architectural remains, can better inform us about how Punic peoples chose to live and express themselves within the Roman empire.

Additional Resources

Bonanno, A. Malta – Phoenician, Punic and Roman. Illustrated edition. Malta: Midsea Books, 2005.

López-Ruiz, Carolina. Phoenicians and the Making of the Mediterranean. Phoenicians and the Making of the Mediterranean. Harvard University Press, 2021.

Quinn, Josephine Crawley. In Search of the Phoenicians. Miriam S. Balmuth Lectures in Ancient History and Archaeology. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018.

Quinn, Josephine Crawley, and Nicholas C. Vella, eds. The Punic Mediterranean: Identities and Identification from Phoenician Settlement to Roman Rule. British School at Rome Studies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107295193.

Wilson, R.J.A. “Becoming Roman Overseas? Sicily and Sardinia in the Later Roman Republic.” In A Companion to the Archaeology of the Roman Republic, 485–504. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2013.

Thelma Beth Minney is a PhD candidate in Classical Archaeology at Stanford University. Her research focuses on religious material remains across the Roman Empire. Her current work investigates the role of material culture in reflecting the shifting identity construction of Punic communities as they were absorbed by Rome between the late Republic and early Empire. Beth uses religious practice as a proxy for identity expression to explore how these communities existing within spaces of active assimilation adapted their local traditions and affordances in accordance with their shifting priorities. She has excavated in both Greece and Italy and is currently a member of the UC Tharros project, focusing on a Punic-Roman urban site in Sardinia. Additional areas of academic interest include topics of cross-cultural transmission, digital approaches to spatial analysis, ethical curation, and reception studies around the intersection of cultural heritage with public engagement.

2 thoughts on “Blog #91: The Punic Peoples of the Western Mediterranean with Thelma Beth Minney”