Peopling the Past brings occasional interviews with researchers on their recently published works.

Phryne the fourth-century hetaira (an upscale female sex worker) is perhaps the most famous sex worker from the ancient Greek world and the subject of a body of anecdotes that portray a witty and beautiful woman who managed to acquire a great fortune and associated with some of the most well-known men of her time. These anecdotes are at turns titillating and comical, yet at the same time they offer hints that the life of Phryne was much more tenuous than her later reputation may suggest. Although I do believe that Phryne was a real woman who likely amassed great wealth and associated with prominent Athenians, we can never truly know all the details of her life (we know little about her origins and nothing about her death, for example).

Instead, my book traces the stories about her to think through how ancient society managed its unease with compelling but unconventional women. Looking at the ways that Phryne’s biographical tradition evolved over time can help us better understand the forces that shape the stories of famous women from the ancient world and identify the missing pieces that the biographical tradition did not preserve, thereby recognizing its limitations. We can also think about the ways that women like Phryne, prominent but marginalized by their foreign status and scandalous profession, offered a means for negotiating anxieties about the position of women in ancient society, both in her own lifetime and the generations that followed.

This project is therefore centered on the most famous stories about Phryne; these involve her nudity, often in very public spaces. In the first pair that I examine, we are told that despite being very careful about the public display of her figure (she apparently even avoided public baths), Phryne attended a religious festival where she was seen bathing in the sea. Among the onlookers that day was one of the most noted artists of the fourth century, Apelles the painter, who is said to have been inspired to create his “Aphrodite Rising from the Sea” by the sight of Phryne in the nude (Athenaeus 13.591a). This was not the only image of the goddess that Phryne was connected to: other stories identify her as the model for Praxiteles’ famous Aphrodite of Knidos (Athenaeus 13.591a), widely known as the first monumental female nude sculpture in the ancient Greek world. Poetry and fictional letters expand on the link between hetaira and sculptor, making them lovers as well.

I also look at what is perhaps the most well-known story about Phryne, and the one that has had the most lasting cultural imprint, her trial for impiety. When it seemed that Phryne was about to be convicted and possibly put to death, her advocate, Hypereides, is said to have pulled off her dress, revealing her beautiful body to the jury of Athenian men and securing her acquittal (Athenaeus 13.590d-f, Plutarch Moralia 849e, Quintilian 2.15.9). In stories like these Phryne’s notoriety and beauty are inextricably tied up in one another, so that her biographical tradition becomes an amalgam of woman, image, and anecdote.

In thinking about stories such as these, which depict a woman who was an incendiary public figure in Classical Athens, I consider how those anecdotes like the ones I’ve related above were shaped by a literary tradition that grew out of fourth century comedy, which made real-life sex workers like Phryne into punchlines. These comedies are in dialogue with historical trials from the same period such as “Against Neaira”, which brought vulnerable, often foreign-born, women into the public eye, thereby making them suitable to joke about on the comic stage. As the cultural center of the Greek world moved to Alexandria with the rise of Macedonian power in the third century BCE, interest in the literature and drama of Classical Athens grew. Authors and scholars in Alexandria took the hetairai (both real and fictional) from fourth-century comedies and paired them with notable men from that period, especially philosophers, in short witty scenes known as chreiai. In these short sketches of life hetairai like Phryne get the best of their higher-status companions and upend traditional social order; the authors depicting these women had turned them from vulnerable sex workers into powerful symbols of Athens.

Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France (LUX 1235), Public Domain

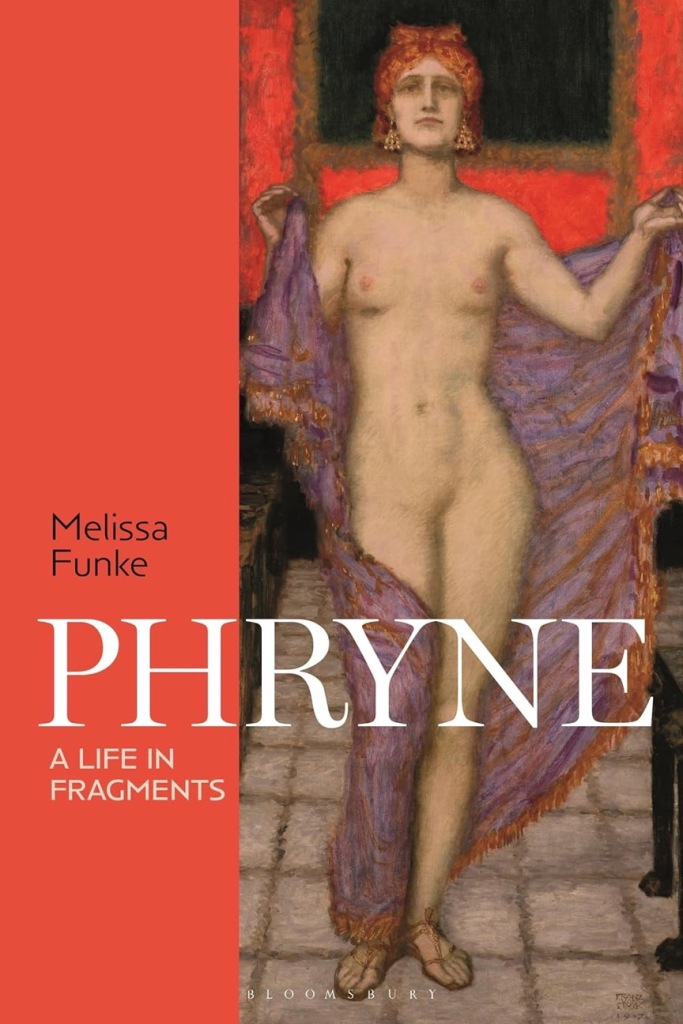

Cover image from book: Franz von Stuck, Phryne, 1917, oil on canvas, Gift of Dr. Anna Berliner, Public Domain, 62.9. Portland Art Museum, Portland, Oregon.

Several centuries later, starting in the first century CE, authors from all over the Roman Empire were writing in Greek, and like their earlier counterparts from Alexandria, they used Classical Athens as the focal point for their displays of learned nostalgia. Quotations of both Classical and Hellenistic texts were used to show the erudition of authors like Athenaeus and so the hetairai featured heavily in such texts, collected and displayed as Classical memorabilia. In Imperial literature, however, we also find a new addition to the depiction of hetairai which centered their perspectives (or what the male authors writing about them envisioned them to be). For example, Alciphron, who wrote four books of fictional letters set in a comic version of Classical Athens, gave voice to Phryne and her peers as he imagined them corresponding with one another about their desires and fears. In Alciphron, Phryne can invite Praxiteles to make love to her (4.1) and in another letter her friend Bacchis can share her relief at Phryne’s acquittal (4.4).

At first glance, Phryne’s biographical tradition seems fulsome but on closer inspection, it is deeply fragmentary, as is the case for so many notable women from the ancient world. When we trace Phryne’s path through literary developments over time we see that her stories are told bit by bit in quotation and anecdote. There is no narrative devoted to the full span of her life nor is she even one of the main characters in an existing text and yet she remains a compelling figure even today. Although fragments like the ones that preserve Phryne’s stories encourage the reader to imagine a presupposed whole, we should embrace the variation that fragmentation introduces and think carefully about the ways that each author that takes up her story uses her narrative to demonstrate erudition and literary innovation.

As we read about the glamourous beauty who stunned a courtroom, we might also use such an anecdote to consider the vulnerability of real sex workers in fourth-century Athens; later narratives work hard to elide that uncomfortable reality in order to create the dream version of Phryne the glamourous beauty. In her own lifetime, a woman like Phryne defied easy categorization and didn’t follow ideals of women’s behaviour, but afterward, her challenging narrative could be broken down into easily consumable anecdotes as the idea of Phryne accrued the kind of cultural capital that the real woman never could.

Additional Reading

Cooper, Craig. (1995), “Hyperides and the Trial of Phryne”, Phoenix 49 (4): 303–18.

Eidinow, Esther. (2016), Envy, Poison, and Death: Women on Trial in Classical Athens Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Funke, Melissa. (2022), “Epistolarity, Eroticism, and Agency: The Female Voice in Fictional Greek Love Letters”, in Anna Tiziana Drago and Owen Hodkinson (eds), Ancient Love Letters: Form, Themes, Approaches, 223–6, Berlin: De Gruyter.

Glazebrook, Allison. (2021), Sexual Labor in the Athenian Courts. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Kapparis, Konstantinos. (2017), Prostitution in the Ancient Greek World, Berlin: De Gruyter.

Kapparis, Konstantinos. (2021), Women in the Law Courts of Classical Athens, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

McClure, Laura K. (2003a), Courtesans at Table: Gender and Greek Literary Culture in Athenaeus, New York: Routledge.

Melissa Funke is Assistant Professor of Classics at the University of Winnipeg and a member of the Ancient Love Letters research network at the University of Leeds. She completed her PhD at the University of Washington with a dissertation on gender in the fragmentary plays of Euripides. Her work focuses on dramatic performance (ancient and modern) as well as gender and status in classical antiquity, particularly as it is depicted in literature; it has appeared in Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies along with several collected volumes. Her current project is a biography of the (in)famous Greek courtesan Phryne that examines the role of anecdote in fashioning literary-historical narratives. She also directs the Lux Project at the University of Winnipeg, which is an outreach project based on a collection of Roman-Egyptian artefacts that aims to make them accessible to both the local community and scholars around the world.

Fabulous work!!

LikeLike