‘When I was a child, I too wanted to be an archaeologist!’. How many times has this been the beginning of a conversation for you? When this exchange took place, were you the one wishing you had pursued archaeology as a profession? Or the one discussing your discoveries with visitors of all ages and social backgrounds?

Archaeology exerts a powerful fascination on people. Recent social media trends, such as asking the men in your life how often do they think about the Roman Empire, have yielded surprising results. According to the UK market research company Ipsos, 41% of the men surveyed thought about the Roman Empire more than once a year. For seven years of my life, I too thought frequently about the Roman Empire, specifically about Hadrian’s Wall, and Roman Britain. I thought about the tangible remains of the Hadrian’s Wall World Heritage Site, about their value as heritage, and about the meanings that individuals have attributed to stones, objects, and landscapes. Most of all, I thought about the identity of those people who, all along, had been adding layers of meaning to the archaeology of Hadrian’s Wall.

Volunteering on the Wall- old or new?

During my PhD, I thought about on the origins of volunteering in archaeology on the Wall. Was volunteering really a new phenomenon? Or had there always been non-professional interest in the Roman remains of Hadrian’s Wall? And if such participation had always been there, why was its study not more widespread? I concluded that the scarcity of research regarding volunteering in archaeological heritage practices relates to the widespread acceptance of definitions of heritage permeated by Authorized Heritage Discourse (AHD) (Waterton, 2005, p. 318; Smith, 2006, pp. 42–43). In other words, the way we are taught to think about the past and to interact with archaeology, places the ‘professional archaeologist’ – a figure which, in Britain, only emerged in the late 19th and early 20th century – on the speaking podium, and turns everyone else, volunteers included, into a listening crowd.

Key texts such as ‘The origins and growth of archaeology’ (Daniel, 1967) or ‘A social history of Archaeology’ (Hudson, 1981) embrace a positivistic, evolutionary view of archaeology, leading straight from the antiquaries of the 1800s to professional archaeologists of today. However, the roles played by those involved in the archaeology of the Wall in its early stages are more complex than it may appear.

Three Examples of Complex Identities in the Archaeology of the Wall

From the most remote to the most modern, let’s look at three examples of excavations on Hadrian’s Wall which involved ‘non-professional’ participation: the Arbeia excavations in 1875–1877, the Birdoswald excavations in 1929, and the Vindolanda excavations from 1970 onwards.

The first excavations at Arbeia were directed by an Exploration Committee. This was composed of prominent South Shields and Newcastle political personalities. One of them, Robert Blair, was a solicitor with ambitions towards becoming an antiquarian. He assumed the role of Secretary of the Exploration Committee and kept a scrapbook (Stewart, 2017) documenting the endeavour. While the Committee appealed to popular interest to raise the funds for the excavations, public participation was limited, if not discouraged. Labourers were pulled from local mining and farming communities and undertook most of the excavation work. When the local South Shields Gazette suggested in one of their printed issues that a volunteer labour force should be used to excavate, a member of the Exploration Committee replied that ‘the fitful, uncertain and irregular work of promiscuous volunteers cannot be relied upon compared to that of men who do a fair day’s work for a fair day’s wage’.

Men digging for a wage, competent in their field but not recognised as ‘archaeologists’, worked on Hadrian’s Wall throughout the early 20th century.

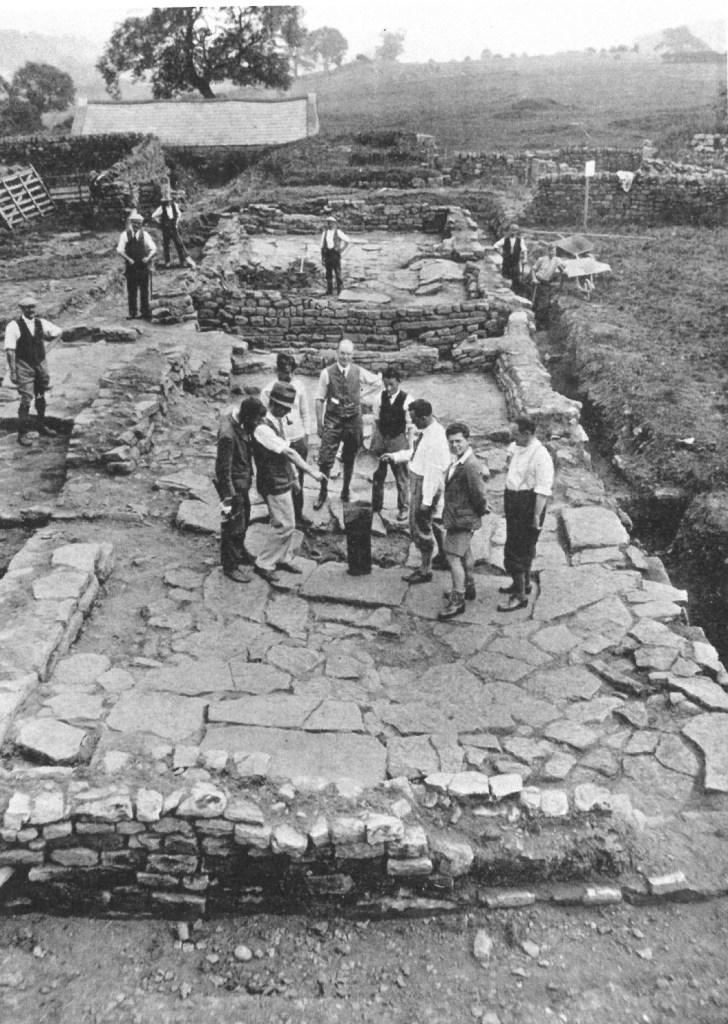

The photograph above represents a group of scholars standing around an altar at the Roman Fort of Birdoswald in 1929. These are the first of a new generation of archaeologists who received university-level training in their discipline. And yet, some distance away we can still see the labourers and excavators, who are not recognised as ‘archaeologists’, but still play a fundamental role in the work. They include foreman Thomas Hepple, who would go on to supervise numerous excavations along Hadrian’s Wall. While technology imposed a static representation of onsite hierarchy, this image portrays, if not the actual roles and relationships between professors, students, and labourers, at least the way that the photographer and excavation director Ian Richmond wanted to portray them. Labourers are deliberately included in the photo, in contrast with their absence in contemporary reports and academic literature. However, they are spatially distant from the students and professional archaeologists in the foreground.

Fast forward to 1970, the Vindolanda Trust was founded on Hadrian’s Wall, with the aim to excavate, research, preserve and present the archaeological remains in its care.

Participation of individuals traditionally labelled as non-professional began at Vindolanda even before the foundation of the Trust (Birley, 2013, p. 133). Groups of volunteers and students from Alnwick college joined the excavations, led by their teacher and director of excavation, Robin Birley. From 1970 to the present day, the volunteering programme at the Trust has evolved, with major milestones including the introduction of a Friends of Vindolanda Membership. This small payment helped to support the work of the Trust, offering unlimited annual visits in exchange. Today, the Trust welcomes volunteers in almost all fields. Museum volunteers assist the curator in the storage and cataloguing of artefacts, volunteer guides lead tours up to four times a day during summer months. In 2025, more than 400 volunteers joined the excavations at the two sites managed by the Trust, and 52 further volunteers joined the Trust’s pottery specialist and geoarchaeologist in processing bulk finds and soil samples. Finally, activities volunteers assist in the delivery of family and schools outreach days.

Conclusions

Even a quick glance at the history of participation in archaeological heritage practices on the Wall reveals an important truth. People whose profession is not archaeology have long been engaging with the Wall’s archaeological remains. ‘Non-professionals’ have always been part of excavating, post-excavating, interpreting and shaping the remains we see today. Therefore, the notion of “peopling the past” should not stop at simply exploring the under-represented voices within the ancient past. We, as researchers, archaeologists, and visitors to archaeological sites, must also consider whose interpretation of the past we are witnessing, and how multivocality has affected it, or not.

Additional Resources

Birley, A.R (2013) ‘Vindolanda’, in C. Walker and N. Carr (eds) Tourism and Archaeology, sustainable meeting grounds. Left Coast Press: Walnut Creek, California, pp. 127–141.

Daniel, G. (1967) The Origins and Growth of Archaeology. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

Hudson, K. (1981) A Social History of Archaeology. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Smith, L. (2006) Uses of heritage. New York: Routledge.

Stewart, M. (2017) ‘South Shields 1875: an early excavation in context’, Archaeologia Aeliana (5) 46, pp. 181-219.

Waterton, E. (2005) ‘Whose Sense of Place? Reconciling Archaeological Perspectives with Community Values: Cultural Landscapes in England’, International journal of heritage studies 11(4), pp. 309–325.

Online resources

Friends, Romans, Britons – Rome is still among us! | Ipsos

Robert Blair’s scrapbook: Front cover – South Tyneside Libraries

Marta Alberti-Dunn is the Deputy Director of Excavations at the Vindolanda Trust, a charity which manages and excavates two sites on Hadrian’s Wall (UK): Vindolanda and Magna. Marta combines her interest in Roman and field archaeology with a passion for public outreach and participatory methods. Her research focuses on volunteer participation to archaeological heritage practices on the Wall. Her work seeks to contribute towards reframing volunteer participation in archaeology both within critical heritage discourse, and within the history of the archaeological profession in Britain. Marta is also a co-founder of the Roman Frontiers ECR Network-Roman Frontiers ECR Network – Connecting early career researchers on the Roman frontiers.

Like our content? Consider donating to Peopling the Past. 100% of all proceeds support honoraria to pay the graduate students and contingent scholars who contribute to the project.

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is appreciated. Please note that we cannot provide tax receipts, as we are not a registered charity.

Your contribution is appreciated. Please note that we cannot provide tax receipts, as we are not a registered charity.

Your contribution is appreciated. Please note that we cannot provide tax receipts, as we are not a registered charity.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearly