In the mid-1960s, a large collection of Cretan armor suddenly appeared on international art markets. The Greek State tracked the hoard to south-central Crete, and Angeliki Lempesi led rescue excavations at the small town of Aphrati in 1968. Following a tip from the looters, Lempesi discovered an impressive hearth temple at the center of an ancient town – a popular architectural design for urban sanctuaries on Crete – that dated to the eighth and seventh centuries BCE. As of January 2026, the armor is split between the Metropolitan Museum in New York; Harvard Art Museum in Cambridge, Massachusetts; Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe in Hamburg; and private collections around the world. As a window into the lives of ancient Cretans, this recent colonial history echoes the ancient history of these objects. They were war booty, stripped from warriors, brought into ancient Cretan cities, and displayed in public spaces.

Nowadays, scholars hypothesize that the Aphrati collection consisted of armor from across the island rather than just Aphrati, but archaeologists are confident that they were looted from urban ritual contexts. Crete, the southernmost island in the Aegean, was a conduit of ideas and technology throughout the eastern Mediterranean. The Cretans created the earliest publicly displayed laws in Europe; some of the earliest city-states, what scholars called poleis; and some of the earliest components of Classical Greek armor. And these three innovations appear to have been related in terms of space and chronology. My current book project seeks to understand the complex balance between martial and political power and its influence on the historical development of Cretan poleis in the Archaic and Classical periods.

In Kate Anderson’s inspirational critique of structural misogyny in archaeology, she distinguishes between two types of ancient actors: warriors and combatants. A combatant is someone who experiences combat, while a warrior is someone who makes the experience of combat part of their identity. In theory, warriors did not actually need to be combatants, since each society ultimately determined the parameters of warriorhood. We have no way of knowing whether Cretans were stripping armor in chaotic inter-polis battles or individual duels, but the booty was regardless representative of a broader warrior ethos, or ideology of violence, that simultaneously reassured victors that they were warriors and defined what warriorhood looked like for subsequent generations. But these pieces also represented another warrior’s failure. Success meant stripping someone of their armor and their ambitions for warriorhood

This embodied duality, between success and failure, is reminiscent to the way in which Rosemarie Garland Thomson frames the disabled or extraordinary body in her seminal book on American Freak Shows in the 19th and 20th centuries. For Thomson, disabled people made up the periphery of the “normate”: an idealized yet unachievable identity which society members sought to embody. The entertainers in Freak Shows performed and presented what it meant to deviate from the “normate”, in terms of their appearance, mental skills, and physical abilities. These performances reassured audiences that they were closer to “normal” than abnormal. Thomson also uses the term cyborg, popularized by Donna Harraway, to describe disabled entertainers, since a cyborg, a human dependent on material or constructed anatomy, is “not subject to Foucault’s biopolitics; the cyborg simulates politics.”

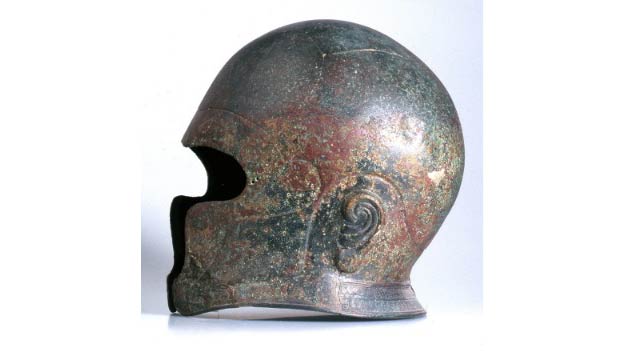

As a heuristic device, the cyborg works well for ancient Crete. Warriors used their metal armor to protect and accentuate their bodies, but when they lost their armor to rival warriors, they were symbolically disassembled and dismembered, failing to actuate the great cybernetic warriors that they claimed to be. This process was deeply political, since warriors were stripping the metal heads, limbs, and groins from their opponents and displaying them in public spaces. The groin guards are particularly striking, not least of all because they outnumber the other armor pieces significantly. Karisthenes’ groin guard, now in Hamburg, is an especially insightful example (see figure 4).

Sometime in the late seventh century BCE, a warrior commissioned this groin guard and wore it into battle. It dangled from the bottom of their corslet by three bronze rings and likely would have made running difficult. This warrior failed, and the guard has the following inscription: ΚΑΡΙΣΘΕΝΗΣ Ο ΠΕΙΘΙΑ ΤΟΝ|Δ ΑΠΗΛΕΥΣΕ, “Karisthenes the son of Peithias took this away [from battle]”. We do not know the identity of the vanquished warrior, but the victorious warrior could not be clearer. Unlike dedicatory inscriptions in other parts of the Greek world, Karisthenes put his own name in the nominative and makes no mention of a god. Scholars continue to debate this distinction: do Cretans make dedications differently or were their war booty not technically dedications – should we think of hearth temples as galleries or temples? The former is a bit unnerving, since it means Cretans were dismembering warrior cyborgs to display their body parts at the heart of the earliest poleis, and their favorite part to display was the groin.

Karisthenes’ groin guard illustrates the differences between ordinary and extraordinary or success and failure. The extraordinary warrior cyborg was incomplete, having non-consensually lost a piece of hir[1] anatomy. The ordinary warrior wrote hir name on that anatomy and deployed it in a new socio-political arena within hir polis. To be part of the “normate”, warriors needed to be successful in combat. They donned their cyborg anatomy to strip opponents’ anatomy, but each piece restricted their sight, hearing, speed, and mobility. Nevertheless, war booty was the measure of success, and that success was contingent on an individual’s martial skill. Whereas weapons and physical training were downplayed in Classical Athens, the Cretans made them a cornerstone of warriorhood. Cyborgs did not relinquish their anatomy willingly and needed to be disassembled through the skillful deployment of violence. The final component of Cretan warriorhood is the most significant for my research. Namely, the Cretan ideologies of violence are all contingent on the assumption that everyone was wearing bronze armor. This material was expensive, decorative, remarkably restrictive, and impractically thin. It did little to prevent injury – and may have even further endangered them – but it was required to be part of the “normate”. Only Cretans with preexisting and secure wealth could afford to opt into warriorhood. But this also created a distinct entry point into warriorhood that could be gatekept and controlled by existing warriors and the polis. In the Classical Period, wealth became the most important component of Cretan warriorhood as Cretan poleis tried (and failed) to create internal military institutions, and Cretan warriors increasingly became the deciding factor in the wars between Athens and Sparta.

[1] This is a portmanteau of “her” and “his” that scholars use to describe a cyborg.

Additional Resources

Anderson, Kate. 2018. “Becoming the Warrior: Constructed Identity or Functional Identity?” In Warfare in Bronze Age Society, edited by Christian Horn and Kristian Kristiansen. Cambridge University Press.

Haggis, Donald, Margaret Mook, Rodney D. Fitzsimons, C. Margaret Scarry, Lynn Snyder, and William C. West III. 2011. “Excavations in the Archaic Civic Buildings at Azoria in 2005-2006.” Hesperia 80: 1–70.

Haraway, Donna J. 2016. A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century. University of Minnesota Press.

Hoffmann, Herbert. 1972. Early Cretan Armorers. Philipp von Zabern.

Konijnendijk, Roel. 2018. Classical Greek Tactics: A Cultural History. Brill.

Lempesi, Angeliki Κ. 1969. “Ἀφρατί.” Deltion 24.

Thomson, Rosemarie Garland. 1997. Extraordinary Bodies: Figuring Physical Disability in American Culture and Literature. Columbia University Press.

Jesse Obert is an Assistant Professor of Ancient Greek History at the University of South Florida. He completed his doctorate in Ancient History and Mediterranean Archaeology at the University of California, Berkeley in 2023, and his current book project, The Hoplite and the Polis: A History of Warriorhood on Archaic and Classical Crete, reassess the role of warriorhood in some of the Greek world’s earliest city-states.

Like our content? Consider donating to Peopling the Past. 100% of all proceeds support honoraria to pay the graduate students and contingent scholars who contribute to the project.

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is appreciated. Please note that we cannot provide tax receipts, as we are not a registered charity.

Your contribution is appreciated. Please note that we cannot provide tax receipts, as we are not a registered charity.

Your contribution is appreciated. Please note that we cannot provide tax receipts, as we are not a registered charity.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearly