In 2021, Peopling the Past ran a month-long blog series in April on human-environment relations. This year, we’re dedicating April to the (related) area of human migration in the past, and its implications for understanding how we came to be who we are through migration, and how we balance our ever-evolving understanding of human movement with senses of place, rootedness, and identity.

In the final installment of Peopling the Past’s Migration Month Blog Series, Elizabeth S. Greene (Brock University) and Justin Leidwanger (Stanford University) discuss fieldwork undertaken under the auspices of the Marzamemi Maritime Heritage Project (MMHP) alongside Leopoldo Repola (Suor Orsola Benincasa University of Naples). This fieldwork documents and makes visible the “ephemeral heritage” encompassed by seagoing vessels used to carry displaced peoples across the Central Mediterranean, including the various objects left behind.

Megan Daniels: As you have noted, this project lies outside the traditional “disciplinary boundaries” of Mediterranean archaeology. What experiences and ideas pushed you to undertake this project? What are your goals for documenting and making visible this “ephemeral heritage”, and have they changed over time?

Elizabeth Greene and Justin Leidwanger: We began our fieldwork in Sicily in 2013, the same year our son was born, with the first season of survey of the late antique “church wreck” at Marzamemi. From a very early age, he napped exclusively in his car seat, while we took turns driving up and down a winding stretch of coastal road. These drives allowed us to witness a changing array of boats year to year, as they moved from shore to port to impoundment area, subject variously to burning, destruction, occasional forms of ad hoc curation, and replacement by new arrivals.

The abandoned or intercepted boats are found frequently along the same shores of southeast Sicily that are better known for ancient shipwrecks, marked by durable stone and ceramic cargoes. Implicated in a new traffic, the modern vessels and their contents are ephemeral; their painted hulls are normally impounded and destroyed, as are the empty water bottles, crumpled clothing and personal items left behind. What began as part of the project’s goals to consider ancient shipwrecks in the context of the local maritime landscape and historic livelihoods on and around the sea led us to examine more closely these material markers of recent connections and their understanding within the community as artifacts of memory. Rescue recording to document these craft before they disappeared led us to consider more immediate and personal stories; as the project develops, we aim to more directly include diverse local communities in the understanding of this heritage and the multivocal narratives it evokes.

MD: At the beginning of your recent article on this project in the American Journal of Archaeology you use the striking term “carceral maritime landscape”, referring to a maritime sphere (the Mediterranean) that restricts “many border crossers to a permanently liminal space.” (p. 80). “Carceral” is not the word most Mediterranean archaeologists use to refer to this basin – it’s most often lauded as a connecter of regions, the prime enabler of human contact going back to the Palaeolithic in this region. What inspired you to use the term “carceral maritime landscape”? Is it a term that applies only to modern scenarios of international borders and restrictive laws concerning border crossings? Or is it a more timeless concept that most archaeologists and historians of the ancient Mediterranean tend to overlook?

EG & JL: The coral-crusted shipwrecks of the Mediterranean have long been seen as markers of timeless connections and cultural interaction, but such romanticized notions gloss over the human faces of mobility and the policies that have also established this middle sea as a dangerous barrier. We have been strongly influenced by Aidonea Dickson’s recent work on the Mediterranean as a carceral space for contemporary migrants through their detention at sea, the increased policing during transit, and the reduction of rights within the maritime landscape. As we look back in time, the contemporary political situation drives us also to consider the often overlooked restrictions to mobility as well as those forcibly carried across maritime space.

MD: Another term you use, borrowed from Sharpe, is “wake work”, evoking the idea of the wake of a ship, as an acknowledgement of those who have attempted these journeys in the past and present. Bringing the experiences of contemporary voyages into our understanding of Mediterranean mobility – so many of which are spurred by forced migration due to war, famine, and climate change – is difficult. You note at the end of your article that there is a tendency to smooth over these horrific pasts, even as we memorialize them through museum installations. How should Mediterranean archaeologists and historians better acknowledge this darker side of human movement across this “Corrupting Sea” in their own research?

EG & JL: We have been struck by the various ways that boats are conceptualized in the heritage sphere: in southeast Sicily, the late antique “church wreck” contains carved marble architectural components destined for a museum; the retired boats of local fishermen serve as local memorabilia or decorative items for piazzas; some are preserved, others left with their ropes, oars and timbers to decay. The migrant boats, on the other hand are confined in restricted port areas as evidence of criminal activity, purposefully detained or erased like the many they carried.

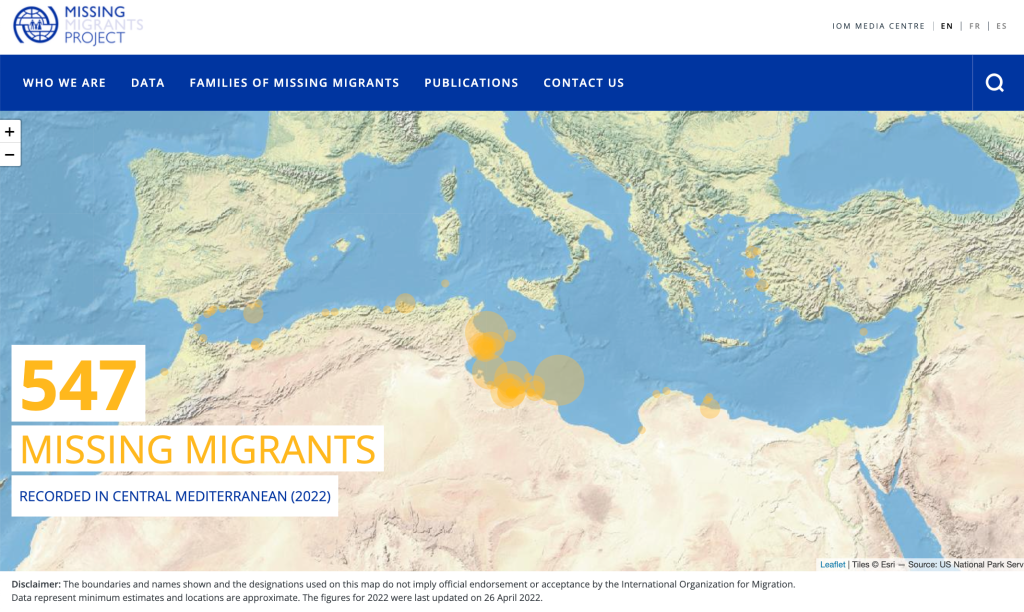

With the metaphor of the wake, the funeral, and the trail of the ship, Sharpe reminds us of the historical commodification of human lives and the work of remembering. For every ship and shipwreck we revisit, we are compelled to consider not only abstract economics and the trade in objects, but the movements of people, of stories, and of lives flourishing or lost. Mediterranean maps produced by the International Organization for Migration’s: Missing Migrants Project offer a stark juxtaposition to the more traditional representations of the sea. Approaching these assemblages with the tools of archaeology allows us to understand better the complex histories of these boats and the layered stories that link past and present in challenging new ways.

MD: You document so many artifacts left behind by the voyagers of Boat #179 at Pozzallo. I couldn’t help but think of archaeological assemblages and all of the human experiences that become erased over time given the ephemeral nature of most materials. This project is a testament to the voyagers of Boat #179, but also to so many forced migrants whose presence was never documented. What aspect of this assemblage has stuck with you the most?

EG & JL: There are so many objects that hold resonance and for this reason the recording process was a challenging experience for all involved. Some were poignant or immediately heart-wrenching, like bag filled with diapers and tiny pink clothes, or the inscribed cover of a Koran. But we were also struck by the large array of blankets in a myriad of weights and patterns. Their labels are lost, fabrics worn, edges frayed, surfaces stained and speckled with chips of blue paint from the deck. The corners are often stretched, knotted, or tied with bits of string or fishing line, revealing changing functions along this and other segments of the journey: bedding, covers, and pillows for sleeping; coats for warmth; floor covers; shade providers; space markers and partitions; baby slings; rucksacks and more. Objects we commonly associate with safety, family, and the comfort of home, here also signal displacement.

MD: Do you see this type of project becoming more of a fixture in “traditional” archaeological research? Should more archaeological projects be adopting a contemporary humanitarian and activist lens as they continue to study the ancient past?

EG & JL: An archaeology of contemporary migration across the central Mediterranean compels us to recognize the long-term continuities of boats, routes, and people who continue to traverse these seas driven by profit and opportunity, but also by displacement from war, politics, and environmental pressure. We feel our own task as archaeologists is incomplete if we only explore the mechanisms of ancient movement without also considering how tales of mythic heroes and imperial conquest have been evoked to justify colonial violence and Eurocentric narratives, or how the discipline of classical archaeology has shaped and contributed to inequality.

Alison Mickel and Kyle Olson have recently argued that the discipline of archaeology is well suited to activism, and for making sure that everyone’s stories are heard. We adhere to the sentiments of Natasha Lyons and Kisha Supernant that archaeology is a labour of care, in which we must recognize and take responsibility for systems of injustice. In an age of displacement driven by unsustainable resource exploitation, climate change, economic inequality, growing populations, systemic racism, and anti-immigrant sentiments, archaeological care for this heritage brings visibility to the many unfinished histories of movement and borders, to the many bridges and barricades across the Mediterranean.

MD: Thank you both for sharing the experiences and lessons from this project. I wrote in my opening blog post, “Lessons from the Past: Archaeology and Migration”, that archaeological accounts of past migrations had long been hampered by scholarly assumptions of cultural, racial, and ethnic purity of human groups in the past (and present), models influenced by archaeology’s 19th-century mission of defining European nation states. These assumptions about cultural immobility have meant that archaeology has always had a fraught relationship with integrating migration and mobility into archaeological explanations, even as new techniques (e.g., aDNA) have emerged to help us map past population movements more accurately. I argued in Homo Migrans that we need to turn to models that recognize migration and mobility as regular and fundamental aspects of human adaptation and development, what I called a “migration-centred worldview”. But a migration-centred worldview does not automatically help us highlight the real human experiences of movement and displacement – like large, circumscribed, immobile “archaeological cultures”, a migration-centred worldview can also subsume a whole number of experiences into neat models. “Ephemeral Heritage” has really opened up this new dimension of the individual lives that are affected by pasts and presents marked by the continuous need to move across landscapes for a myriad of reasons. I hope future studies and narratives can lean towards an acknowledgement of these very human experiences as much as possible as they engage with vogue topics like “Mediterranean connectivity”. I’ve also come to see how we cannot understand migration and mobility without understanding rootedness, identity, and belonging. Movement and rootedness are two sides of the same coin – while they are seemingly opposites, one cannot exist without the other. I think a focus on rootedness can also help remind us of the lives that are altered and lost through migration. I hope we’ll devise more realistic ways to understand past peoples in a way that honours both movement and identities, however complex and shifting both of these phenomena can be.

Further Resources

Ben Zion, I. 2018. “Shipping Stone.” Archaeology Magazine (Sept/Oct): 50-55. https://www.archaeology.org/issues/309-1809/features/6856-sicily-byzantine-shipwreck

Dickson, A.J. 2021. “The Carceral Wet: Hollowing Out Rights for Migrants in Maritime Geographies.” Political Geography 90:102475. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0962629821001359

Greene, E.S., J. Leidwanger, and L. Repola. 2022. “Ephemeral Heritage: Migration, Boats and Heritage in the Central Mediterranean Passage.” American Journal of Archaeology 126.1: 79-102. https://www.ajaonline.org/article/4414

Mickel, A. and K. Olson. 2021. “Archaeologists Should Be Activists Too.” Sapiens (27 July). https://www.sapiens.org/archaeology/archaeology-activists/.

Sharpe, C. 2016. In the Wake: On Blackness and Being. Durham: Duke University Press.

Supernant, K., J.E. Baxter, N. Lyons, and S. Atalay, eds. 2020. Archaeologies of the Heart. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

Elizabeth S. Greene is an Associate Professor in the Department of Classics and Archaeology at Brock University in St Catharines, Ontario. Her research concerns seaborne mobility and interaction across the Mediterranean, focusing on material evidence for long-term processes of trade and exchange, fishing traditions and communities, and human displacement and migration. In Turkey and Sicily, she has conducted archaeological field research and heritage work on shipwrecks, port sites, and maritime landscapes ranging from Archaic to contemporary. She serves as 1st Vice President of the Archaeological Institute of America, having previously held the position of Vice President for Cultural Heritage (2017-2020). Through this service, she advocates an inclusive, global, and ethical framework for archaeology in the Mediterranean and beyond.

Justin Leidwanger is an Associate Professor in Stanford University’s Department of Classics and faculty at the Stanford Archaeology Center. His research focuses on Mediterranean mobilities, port communities, and systems of exchange, interests he explores through community-based archaeology of the ships, coastal landscapes, and tangible and intangible heritage of historic and contemporary maritime life at the tip of southeast Sicily. He led investigations (2013-2019) of the famous 6th-century Marzamemi “church wreck,” work that has grown now to interrogate the heritage diverse but co-dependent interactions with and across the sea that have long defined the central Mediterranean and offer a resource for deeper engagement with the past and sustainable future development.