For Halloween month, our blog posts focus on the theme “Cursing in the Ancient World”. Our authors explore the notorious practices of curse tablets and other magical spells, and reflect on the deeper human tendencies that underpin these acts.

Content Warning: Strong language used in this post

What Topic do You Research?

I am just finishing my PhD at the University of Exeter, UK in the department of Classics, Ancient History, Theology, and Religion. My research focuses on close reading of curse tablets to ascertain how ancient individuals conceived of the role of the dead and the gods in the carrying out of the curse. One of the core questions which has arisen throughout my research is whether the creation of a curse tablet is an inherently magical act or whether it was viewed as a ritual which fitted into the wider lived religious experience of ancient individuals. Spoiler alert – it is the later!

What sources or data do you use?

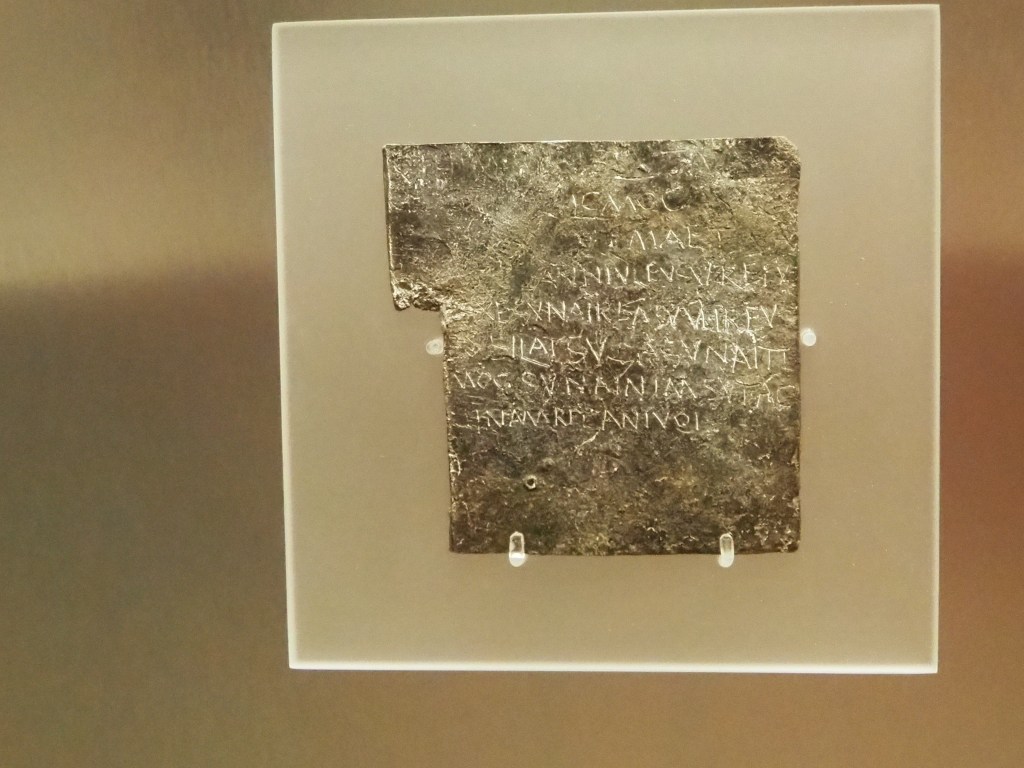

These are small inscriptions, usually on lead tablets but also on papyrus scraps, ostraca, wax, parchment, and paper. There are currently roughly 2,000 published tablets but this number is rapidly increasing.

These inscriptions were written by a variety of people (men, women, enslaved individuals) from the late sixth century BCE through until the eight century CE, there are a couple of examples which date even later into the tenth and eleventh centuries CE. Curse tablets are found in every country surrounding the Mediterranean, as well as Portugal, Britain, Germany, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Austria, Russia, and Ukraine. I work with inscriptions in Latin, Greek, Celtic, Oscan, Punic, and Etruscan. Some of these tablets were written by professional scribes or individuals with professional levels of ritual knowledge. However, the majority appear to have been written by ordinary individuals.

I only work with published tablets and have not (yet) been able to undertake my own physical autopsy of any tablets. However, many of the tablets are published in scattered journal articles. This is particularly the case with the Greek examples, and a large part of my thesis is a catalogue where I have tried to draw together all of the relevant examples in order to make future work with these sources much easier.

How does this research shed light on real people in the past?

These curse tablets are written by individuals from across the social spectrum in the ancient world. Often, we only have the thoughts or opinions of individuals from higher levels of society, but these tablets provide a corrective to that. In some cases, it is clear that individuals have had to turn to the creation of a curse tablet in order to access help from a god or goddess because there is nowhere else to turn. For example, we have a cache of curse tablets from the temple of Demeter and Cnidus, dated to the first or second century BCE:

DT 1:

Side A:

Ἀνιεροῖ Ἀντιγό

νη Δάματρι Κού-

ραι Πλούτωνι θε-

οῖς τοῖς παρὰ Δά-

ματρι ἅπασι καὶ

πάσαις · εἰ μὲν ἐ-

γὼ ϕάρμακον Ἀ-

σκλ[α]πιάδαι ἢ ἔ-

δ[ωκ]α, ἢ ἐνεθυ-

μήθ[η]ν κατὰ ψ-

[υ]χὴν κακόν τι

[α]ὐτῶ ποῖσαι, ἢ ἐ-

κάλεσα γυναῖκ

α ἐπὶ τὸ ἱερόν,

τρία ἡμιμναῖ-

α διδοῦσα ἵνα

{ι}αὐτὸν ἐκ τῶν

ζώντων ἄρη,

ἀναβαῖ Ἀντιγό-

νη πὰ Δάμα-

τρα πεπρημέ-

να ἐξομολοῦσ̣[α],

καὶ μ[ὴ] γένοιτο

εὐειλάτ[ου] τυ-

χεῖν Δάματρο[ς],

ἀλλὰ μεγάλα-

ς βασάνους βασ-

ανιζομένα · εἰ δ᾽ εἶ[-

πέ] τις κατ᾽ ἐμοῦ π-

ρὸς Ἀσκλαπιδα, εἰ κ-

[α]τ᾽ ἐμοῦ καὶ παριστ-

άνετα[ι] γυναῖκα

χαλκοῦς δοσα

ιανασμουια

[——-]

Side B:

[——-]

[——-]

[——-]

[——-]

[——-]

[——-]

[——-]

[——-]

[——-]

[——-]

[——-]

[——-]

[——-]

[——-]

[——-]

[——-]

[——-]

[——-]

[——-]

[——-]

[——-]

[——-]

ἐμοὶ δ᾽ ὅσια καὶ

εἰς βαλανέον

καὶ ὑπὸ ταὐτὸ

στέγος εἰσελ-

θεῖν καὶ ἐπὶ τὰ-

ν αὐτὰν τρπ-

εζαν.

Text: Audollent 1904: no. 1.

Side A:

Antigone dedicates to Demeter, Persephone, Pluto, and all the gods beside Demeter, both male and female. If I have given a potion to Asklapiadas or conceived in my spirit of doing anything bad to him, or have summoned a woman to the temple, giving her 3 half-minai, so that she might take him from the living, let Antigone come to the temple before Demeter, burning, and confess, and may Antigone not find Demeter merciful, but may she be tormented with great suffering. And if anyone says anything against me to Asklapiadas, if (anyone) brings forward (as a witness) against me a woman giving her coppers …

Side B:

But let me go, innocent of any profanity, both into the baths, and under the same roof, and to the same table (as the person I am cursing).

In this example if the woman who created the tablet was found guilty of plotting the demise of Asklapiadas then her punishment would have been death… The creation of this tablet is literally her fighting for her life.

(Photo by: Marie-Lan Nguyen CC Attribution 2.5 Generic)

Not all tablets were quite so driven by a desire for justice. We have a category of curses called ‘erotic magic’ often the requests by the individuals who created these tablets were more sinister. For example, in this example (which is accompanied by a figurine known as the Louvre Doll), which is dated to the third or fourth century CE and comes from Egypt, the daimon is directed to forcefully drag the unwilling female victim to the male curse-creator:

TheDefix. 110:

παρακατατίθεμαι ὑμῖν τοῦτον τὸν κατάδεσμον, θεοῖς καταχθονίοις, Πλούτωνι καὶ ΚόρῃΦερσεθόνῃ

Ερεσχιγαλ καὶ ᾿Αδώνιδι τῷ καὶ Βαρβαριθα καὶ ῾Ερμῇ καταχθονίῳ Θωουθ φωκενσψευ ερεκτׅαθου μισον-

κταικ καὶ ᾿Ανούβιδι κραταιῷ Ψηριφθα, τῷ τὰς κλεῖδας ἔχοντι τῶν κατὰ ῾´Ανούς, καὶ δαίμοσι κατα-

χθονίοις, θεοῖς, ἀώροις τε καὶ ἀώραις, μέλλαξι καὶ παρθένοις, ἐνιαυτοῖς ἐξ ἐνιαυγῶν, μήνασι

ἐκ μηνῶν. ἡμέραις ἐκ ἡμερῶν, ὥρασι <ἐξ> ὡρῶν, νύκτες ἐκ νυκτῶν· ὁρκίζω πάντας τοὺς δαί-

μονας τοὺς ἐν τῷ τόπῳ τούτῳ συνπαραστῆναι τῷ δαίμονι τούτῳ ᾿Αντινόῳ διέγειραί μοι σε-

αυτὸν καὶ ὕπαγε εἰς πᾶν τόπον, εἰς πᾶν ἄμφ̣ο̣δον, εἰς πᾶσαν οἰκείαν, καὶ κατάδησον Πτολε-

μαΐδα, ἣν ἔτεκεν ᾿Αϊᾶς, τὴν θυγατέρα ῾Ωριγένους, ὅπως μὴ βινηθῇ, μὴ πυγισθῇ, μη-

δὲν πρὸς ἡδονὴν ποιήσῃ ἑταίρῳ ἀνδρὶ εἰ μὴ ἐμοὶ μὸνῳ, τῷ Σαραπάμμωνι, ὃν ἔτε-

κεν ᾿Αρέα, καὶ μὴ ἀφῇς αὐτὴν φαγεῖν, μὴ πεῖν, μὴ στέγειν μήτε ἐξελθεῖν μήτε

ὕπνου τυχεῖν ἐκτος ἐμοῦ, τοῦ Σαραπάμμωνος, οὗ ἔτεκεν ᾿Αρέαἐξορκιζω σε, νεκύδαιμον

᾿Αντίνοε, κατὰ τοῦ ὀνόματος [τοῦ] τρομεροῦ καὶ φοβεροῦ, οὗ ἡ γῆ ἀκούσασα τοῦ ὀνό-

ματος ἀνυγήσεται, οὖ οἱ δαίμονες ἀκούσαντες τοῦ ὀνόματος ἐνφόβως

φοβοῦται,

οὗ οἱ ποταμοὶ καὶ πέτραι ἀκούσαντες <τοῦ ὀνόματος > ῥήσσ̣[οντα]ι ὁρκίζω σε, νεκυ’δαιμον ᾿Αντίνοε,

κατὰ τοῦ Βαρβαραθαμ χελουμβρ̣α βαρ̣ρ̣υ̣[χ] Αδωναι καὶ κατὰ τοῦ Αβρασαξ καὶ

κατὰ τοῦ Ιαω πακεπτωθ πακεβραωθ σαβαρβαθαει καὶ κατὰ

τοῦ Μαρμαραουωθ καὶ κατὰ τοῦ Μαρμαραχθα μ̣αμαζαγαρ̣· μὴ παρα-

κούσῃς, νεκύδαιμον ᾿Αντίνοε, ἀλλα’ ἔψειραί μοι σεαυτὸν καὶ ὓπαγε εἰς πᾶν τό-

τον, εἰς πᾶν το-

τον, εἰς πᾶν ἄμφοδον, εἰς πᾶσαν οἰκειαν καὶ ἄγαγέ μοι τὴν Πτολεμαΐδα,

ἣν ἔτ̣εκεν ᾿Αϊᾶ̣ς, τὴν θυγατέρα ῾Ωριγένους· κατασχες αὐτῆς τὸ βροτόν,

τὸ ποτόν, ἕως ἔ̣λθῃ πρὸς ἐμέ, τὸν Σαραπάμμωνα, ὃν ἔτεκεν᾿Αρέα,

καὶ μὴ ἐάσῃς αὐτὴν ἄλλου ἀνδρὸς πεῖραν λαβεῖν εἰ μὴ ἐμοῦ μόνου,

τοῦ Σαραπάμμωνος· ἕλκε αὐτ̣ὴ̣ν τῶν τριχῶν, τῶν σπλάγχνων,

ἕως μὴ ἀποστῇ μου, τοῦ Σαραπάμμωνος, οὗ ἔτεκεν ᾿Αρέ̣α. καὶ ἐχω

αὐτήν, τὴν Πτολεμαΐδα, ἣν ἔτεκεν ᾿Αϊᾶς, τὴν θυγατέρα ῾Ωριγένους,

ὑποτεταγμένην εἰς τὸν ἅπαντα χρόνον τῆς ζωῆς μου,

φιλοῦσάν με, ἐρῶσ[ά]ν μου, λέγουσάν μοι ἃ ἔχει ἐν νόῳ. ἐὰν τοῦτο

ποιήσῃς, ἀπολδύσω σε.

I deposit this binding charm with you, chthonic gods, Plouton, Kore Persephone, Ereschigal and Adonis, also called Barbaritha, and chthonic Hermes Thoth Phôkensepseu erektathou misonktaik and mighty Anoubis Psêriphtha, who holds the keys of the gates to Hades, and chthonic daemons, gods, men and women who suffered an untimely death, youth and maidens, year after year, month after month, day after day, hour after hour, night after night. I adjure all the daemons in this place to assist this daemon Antinoos. Rouse yourself for me and go into every place, into every quarter, into every house, and bind Ptolemais, whom Aias bore, the daughter of Horigenes, so that she not be fucked, not buggered, not do anything for the pleasure of another man, except for me Sarapammon only, whom Area bore, and do not allow her to eat, to drink, to resist or to go out or to get sleep apart from me, Sarapammon, whom Area bore. I adjure you, corpse-daemon Antinoos, by the dreadful and frightful name of the one at the sound of whose name the earth will open, at the sound of whose name the daemons tremble fearfully, at the sound of whose name the rivers and the rocks break. I adjure you, corpse-daemon Antinoos, by Barbaratham cheloumbra barouch Adônai and by Abrasax and by Iaô pakeptôth pakebraôth sabarbaphaei and by Marmaraouôth and by Marmarachtha mamazagar. Do not disobey, corpse-daemon Antinoos, but rouse yourself for me and go into every place, into every quarter, into every house and bring me Ptolemais, whom Aias bore, the daughter of Horigenes. Keep her from eating and drinking until she comes to me, Sarapammon, whom Area bore, and do not allow her to have experience of another man except me Sarapammon only. Drag her by the hair, by the inward parts until she does not stand aloof form from me, Sarapammon, whom Area bore, and I have her, Ptolemais, whom Aias bore, the daughter of Horigenes, subject for the entire time of my life, being fond of me, loving me, telling me what she has in mind. If you do this, I will set you free.

Text and translation: Daniel and Maltomini 1991: 179-183.

The disparity between these two examples is typical of curses. A curse tablet could be created for as a result of almost any issue, such as the loss of a cloak or a small amount of coinage through to the desire that your enemies lose in a legal trial. They reflect the vastness of the human experience, even in the modern world. We see people struggling with similar issues all around us. What is incredible is that we can gain these personal insights into ancient lives which were being lived over 2,000 years ago.

Further Resources

Collins, D. 2008. Magic in the Ancient Greek World. Oxford.

Daniel, R. and Maltomimi, F. (eds.) 1990–1992. Supplementum Magicum. Papyrologica Coloniensia. Cologne.

Eidinow, E. 2013. Oracles, Curses, and Risk Among the Ancient Greeks. Oxford. Second Edition.

Faraone, C. A. 1999. Ancient Greek Love Magic. Cambridge, Mass.

Faraone, C. A. 2011. ‘Curses, Crime Detection and Conflict Resolution at the Festival of Demeter Thesmophoros,’ The Journal of Hellenic Studies 131: 25–44.

Faraone, C. A. and Obbink, D. (eds.) 1991. Magika hiera: Ancient Greek Love Magic and Religion. Cambridge, Mass.

Faraone, C. A. and Torallas Tovar, S.(eds.) 2022. Greek and Egyptian magical formularies, vol. I: text and translation. California classical studies, 9. Berkeley.

Gager, J. 1992. Curse Tablets and Binding Spells from the Ancient World. Oxford.

Gordon, R. 2012. ‘Fixing the Race: Managing the Risks in the North African Circus,’ in Piranomonte, M. and Marco Simόn, F. (eds.) Contextos mágicos/ Contesti magici. Atti del Convegno Internazionale, Roma, 4–6 novembre 2009. Rome. 35–62.

Gordon, R. 2015. ‘Showing the Gods the Way: Curse-Tablets as Deictic Persuasion,’ Religion in the Roman Empire 1: 148–180.

Graham, E.-J. 2021. Reassembling Religion in Roman Italy. Oxford.

Hope, V. M. 2009. Roman Death. London.

Jordan, D. R. 1985c. ‘A survey of Greek Defixiones not Included in the Special Corpora,’ Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies 26: 151–197.

Jordan, D. R. 2000. ‘New Greek Curse Tablets (1985-2000),’ Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies 41: 5–46.

Jordan, D. R. 2022. ‘Curse Tablets of the Roman Period from the Athenian Agora,’ Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens 91: 133–210.

Kearns, E. 2010. Ancient Greek Religion: A Sourcebook. Oxford.

Kindt, J. (ed.) Forthcoming (2024). Ancient Greek Personal Religion. Cambridge.

Kindt, J. 2012. Rethinking Greek Religion. Cambridge.

Lamont, J. L. 2023. In Blood and Ashes: Curse Tablets and Binding Spells in Ancient Greece. Oxford.

McKie, S. 2022. Living and Cursing in the Roman West: Curse Tablets and Society. Oxford and New York.

Ogden, D. 1999. ‘Binding Spells: Curse Tablets and Voodoo Dolls,’ in Arkarloo, B. and Clarke, S. (eds.) The Athlone History of Witchcraft and Magic in Europe. Vol. 2. Ancient Greece and Rome. London. 3–90.

Ogden, D. 2008. Night’s Black Agents: Witches, Wizards and the Dead in the Ancient World. London and New York.

Ogden, D. 2009. Magic, Witchcraft, and Ghosts in the Greek and Roman Worlds: A Source Book. Second Edition. Oxford.

Salvo, I. 2012. ‘Sweet Revenge: Emotional Factors in the “Prayers for Justice”,’ in Chaniotis, A. (ed.), Unveiling Emotions: Sources and Methods for the Study of Emotions in the Greek World. Stuttgart. 236–266.

Salvo, I. 2020. ‘Experiencing Curses: Neurobehavioral Traits of Ritual and Spatiality in the Roman Empire,’ in V. Gasparini, M. Patzelt, R. Raja, A.-K. Rieger, J. Rüpke, and E. Urciudi (eds.) Lived Religion in the Ancient Mediterranean World. Berlin. 157–180.

Sánchez Natalías, C. 2022. Sylloge of Defixiones from the Roman West. Oxford.

Sourvinou- Inwood, C. 2000a. ‘What is Polis Religion?’, in Buxton, R. (ed.) Oxford Readings in Greek Religion. Oxford. 13–37. (First published in Murray, O. and Price, S. (eds.) 1990. The Greek City from Homer to Alexander. Oxford. 295–322.)

Sourvinou- Inwood, C. 2000b. ‘Further Aspects of Polis Religion’, in Buxton, R. (ed.) Oxford Readings in Greek Religion. Oxford. 38–55. (First published 1988 in AION (archeol) 10 259–74.)

Spence, C. 2022c. ‘Change and Continuity in Curse Tablets from the Roman World,’ in Conti, F. and Pollard, E. (eds.) Nemo non metuit: Magic in the Roman World. Budapest. 53–98.

Tomlin, R. S. O. 1988. ‘The Curse Tablets,’ in Cunliffe, B. (ed.) The Temple of Sulis Minerva at Bath Volume 2: The Finds from the Sacred Spring. Oxford. 59–227.

Urbanová, D. 2018. Latin Curse Tablets of the Roman Empire. Innsbruck.

Online Resources:

https://www.thedefix.uni-hamburg.de

http://curses.csad.ox.ac.uk/beginners/

Charlotte Spence’s research focuses on the conceptions of the dead and divine in Greek and Latin curse tablets from the late sixth century BCE through until the ninth century CE. As well as presenting her research at international conferences; she has also published on curse tablets in the Roman world and has forthcoming publications on the curse tablets of Carthage as well as on Personal Religion in the Greek world. Charlotte is in the early stages of considering how the use of AI technology could improve our reading and dating of these texts.

“Such an inspiring read! Charlotte Spence’s journey into the world of ancient history and her passion for peopling the past is truly captivating. Her dedication to uncovering narratives through archaeological textiles is commendable. Thank you for sharing her story!”

LikeLike

Fantastic feature on Charlotte Spence! The insights into her journey as a graduate student are both inspiring and enlightening. Thanks for sharing such an engaging and informative post!

LikeLike

Fantastic insight into Charlotte Spence’s journey! Her passion for ancient history and dedication to her research are truly inspiring. A great read that highlights the importance of young scholars in the field.

LikeLike