For Halloween month, our blog posts focus on the theme “Cursing in the Ancient World”. Our authors explore the notorious practices of curse tablets and other magical spells, and reflect on the deeper human tendencies that underpin these acts.

In our latest instalment of our Halloween series on “Cursing in the Ancient World” we are interviewing Dr. Jessica Lamont, Assistant Professor at Yale University, on her newly published book through Oxford “In Blood and Ashes: Curse Tablets and Binding Spells in Ancient Greece.” Dr. Lamont shares with us the questions and research that inspire this work, providing remarkable insight into the real people behind the curses in the ancient Mediterranean.

Congratulations first of all on this fantastic monograph. I’m interested, first of all, in knowing what drove you to this research? Why did you feel this book needed to be written?

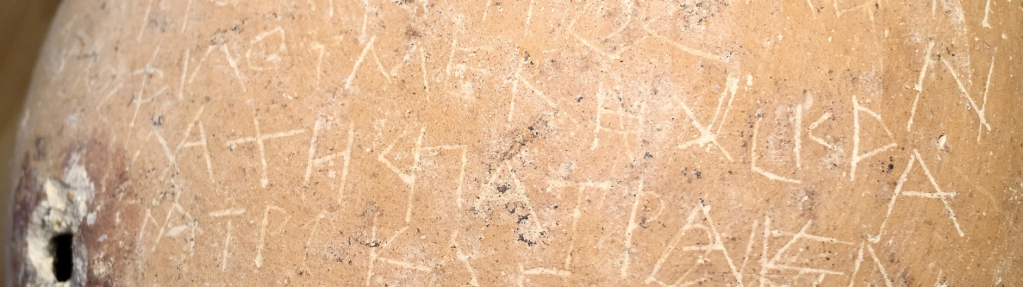

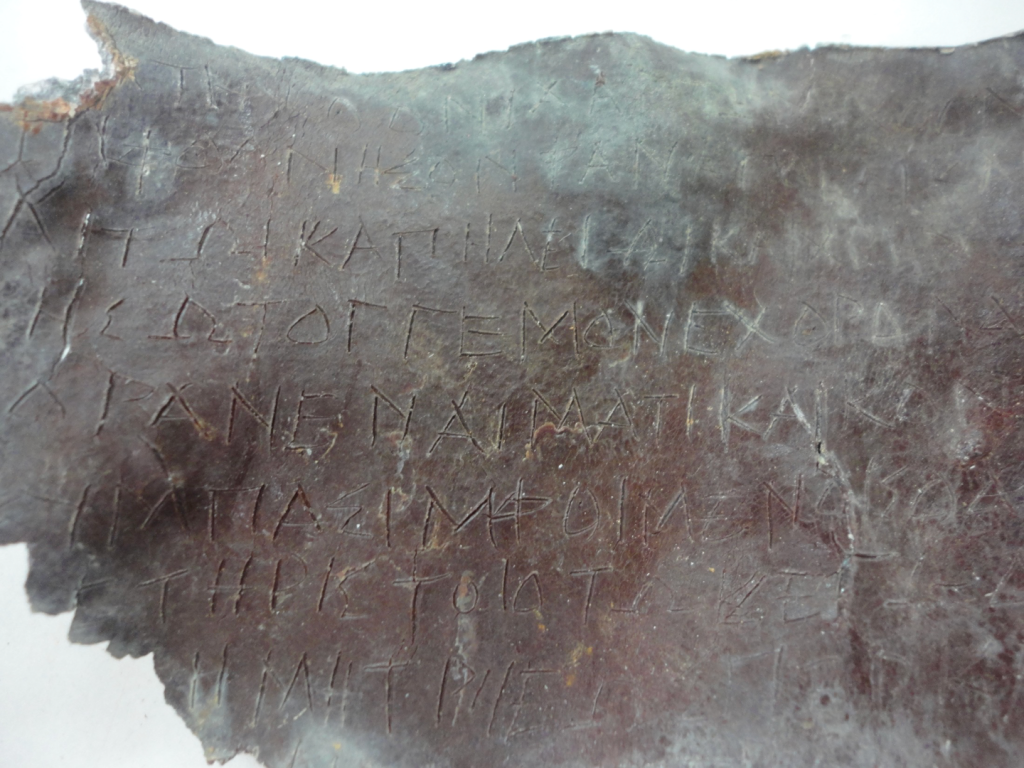

Thank you. Working with these inscriptions is always good fun, and always a challenge—each text poses its own riddles: sometimes letters are written backwards or scrambled, sometimes syllables are reversed, whole lines can be written backwards, upside down, or alternated. Some curses are palimpsest-like, and saw reuse in antiquity. Others were inscribed on lead staples or ceramic pots (See Figs. 1 and 2). Then, once (if) you work out a curse text, the context can pose its own mysteries (why was a curse tablet buried beneath the Tholos in the Athenian Agora, e.g.?), as can the conflict which occasioned the curse, questions of prosopography, and so on.

But aside from the fun, what drew me in deeper were the voices that these objects capture, and their potential for expanding modern understandings of daily life, religion, and social history in Classical antiquity. These objects preserve diverse sets of narratives: an amphora seller and barber in the Athenian Agora, a helmsman transporting enslaved persons in the northern Black Sea, a wealthy sponsor of choragic competitions in coastal Sicily, and a female garland weaver in Roman Corinth. As sources for social history, I use these objects to show how individuals were managing conflict, competition, and vulnerability in ancient Greek communities, and engaging with the gods, the dead, and the Underworld in rites meant to change the present and future course of events.

Finally, it was clear to me that these objects represented a very widespread ritual technology that spanned from the northern Black Sea to North Africa to Roman Britain. The practice spread rapidly and widely over time and space, and was adopted and adapted by the persons with whom the Greeks and Romans came into contact, from Oscans to Carthaginians to Celts to Iberians. We now have so many curse tablets and effigies, with more coming up each year, but there was no history that tried to contextualize this development historically, and study the spread of curse-writing and other “magic” technologies, while also showing how the practice changed over time. I wanted to work out that history in order to better comprehend a fascinating, widespread, yet poorly understood phenomenon.

From your research, are there specific categories of spells that we could organize the ancient evidence into? What were the most effective ways of cursing and binding in the ancient world?

There are a few ways to do this, sure. One can think in terms of materials used (wax, animals, ceramic, lead), spell-types (erotic binding spells, hexameter incantations), object types (effigies, lead tablets, ceramic pots), etc. Magical “technologies” if you prefer, all of which reflect different forms of knowledge on the part of their practitioners, whether this was an oral hexameter incantation meant to staunch a bleeding flesh wound—already present in the earliest Greek poetry (Hom. Od. 19.455-8)—the charm used by a midwife to bring on a speedy birth, amulets used to prevent the internal wandering of the uterus and its attendant health complications, the moulding of curse effigies of wax or lead, the use of animals and organics in spells and potions, and so on. Knowledge about curse-rituals also included wider forms of ritual knowledge that extended beyond the writing-down of a curse text on lead or ceramic (see Figs. 3 and 4), though it is this part of the ritual that is visible to us millennia later in the archaeological record, and thus provides, at the very least, an entry point into wider magical practices.

Do you get the sense that all of the activities associated with cursing and binding were kind of niche, even taboo activities? I note, for instance, your mention of Plato’s ideas for punishing curse casters in Laws (execution in some cases!), so there clearly seemed to be some segments of society who were against these practices. I’m interested in your general perception of their popularity and acceptance in ancient Mediterranean societies.

My opinion is that yes, these were taboo activities, hence their near invisibility in contemporary Greek literary sources, but their abundance in the archaeological record. Popular yes, on the basis of sheer quantity. Accepted is harder to speak to. Accepted in the sense that we don’t know of historical legislation in Athens against the creation of katadesmoi or curse effigies (see Figs. 5-6), and accepted in the sense that there is evidence for these rites being performed not infrequently (well over 520 curses survive from Athens, and more are continuously emerging). But these probably were taboo practices, as they meant to debilitate or incapacitate or, in some cases (in my opinion), outright harm other members of the social community. Earlier scholars have argued that it was all about competition, and not violence, but I find it hard to see how phrases such as “I bind my enemy in blood and ashes, together with all the dead!”, which finds parallels in the most striking death scenes in early epic, did not intend some real harm against their targets. These were created in high-stakes situations, moments of feverish crisis, vulnerability, anxiety, and (certainly also) competition. But they were ultimately enacted against other members of a social community, and it’s difficult to envision that the community as a whole would have supported such anti-social rites.

From the legal nature of the written language in early curse tablets, you suggest that these tablets might have been understood as “ritual extensions of law court practice” (p. 42). Yet they were most often deposited in graves and some sanctuaries, while some involve non-legal spheres (e.g., choral competitions). I find this intertwinement of different spheres fascinating. This intertwinement raises questions about the literacy and expertise behind them – can we understand anything about the people (their identities, professions, and education) who would have been able to write these texts, who must have had a good deal of ritual as well as legal, scribal, and other expertise?

First: yes, it is my sense in terms of both the earliest Greek curse texts, which mention “witnesses,” “co-speakers,” “court advocates,” “court,” and so on, in addition to the concept of ateleia (which also had legal significance), that early Greek curse-writing rituals developed for use in legal contexts, that is, in the late Archaic lawcourts of western Greek polities like (especially) Selinous. We can see a bit into the historical backdrop of Selinous at this time. The broader picture, if hazy in detail, is one of social and political turbulence—there is evidence for multiple tyrannies, mass exilings, homicide, probably land confiscations, and more. Sometimes aspects of these conflicts played out in the lawcourts, and this seems to be what is documented in the earliest curse tablets.

Important, too, are the persons who feature in the earliest curse tablets—we find reference to wealthy individuals and even to gentilician groups. In a single early curse tablet from Selinous in western Sicily, we encounter three members of the Heracleid genos: Xenios the son of Apontis of the Herakleidai, Athanis the son of Tammaros of the Herakleidai, and Agathullos son of Xenios of the Herakleidai. These, in other words, were men of wealth and means, who were literate, savvy, and possessed the resources to advance and protect their interests in the courts of law.

Another early curse tablet from a few generations later (provenance unfortunately is murky) concerns a choragic dispute, and involves someone wealthy enough to sponsor a Sicilian chorus, and who also, independently, had served as proxenos—again, we are in the world of wealthy and well-connected upper-class aristocrats.

Curse tablets thus emerge firmly within the aristocratic ethos of the late Archaic city- state, often in legal contexts among competing elites, with texts composed in the Greek language and script. While some scholarship has associated the early use of curse tablets with Selinous’s lower classes, I show that it was in fact the city’s Greek, aristocratic gene— powerful, wealthy, and literate, with great resources at their fingertips— who first deployed curse-writing rituals in the courts of law. These were the families with much at stake at trial, and the resources to first procure and produce the objects surveyed in Chapters 1-2 of my book. Women, it might be added, also appear in not a few of these early Sicilian legal curses. Does the cursing in an early lead tablet from Selinous of Timaso and Tyranna, and both of their tongues, suggest that these women could testify at trial in Selinous? How was an individual like Tyrrana, whose name signals some sort of relationship with Etruria or Etruscan groups, connected to Selinontios and to the commissioner of the curse— and what was the nature of the conflict that brought them all together in court?

And finally, yes, some of these early inscribed objects were surely the work of ritual professionals—literate individuals who had the technological know-how to compose a curse with inverted or twisted characters, and attend to its deposition in a grave or chthonic sanctuary. I do think it’s possible that women and family groups played some role in the deposition of curse assemblages, especially as the preparation of the corpse and the tending of the grave was often undertaken in this period by women; sanctuaries of Demeter and Kore/Persephone were, similarly, places that allowed for active female worship. And these are the two contexts in which early Greek curse tablets were being deposited, with the goal of reaching the powers of the Underworld who could enact the curse or spell.

Can you tell us about one of the most striking curse tablets or effigies you’ve encountered in your research? Which one sticks in your mind?

Hmmm, maybe Theophrastos of Paros (see Fig. 7). This was a curse effigy excavated in a tile grave on the Cycladic island of Paros—the object itself is a heavy, cast lead figurine that fits in your hand, dating from the early fourth century BCE. The figurine was pierced with seven iron nails (one through the mouth, one through each eye, three through the skull, one through the anus), the arms were bound behind the back, and a lead collar shackled the neck. Many find the object startling, unsettling—people are often surprised to learn that such an object was produced in Classical Greece.

Inscriptions on the body in the epichoric Parian alphabet suggest that the object was produced locally: <Ω> is used to indicate short O (/o, o:/), so Θεώφραστως, rather than Θεόφραστος. The use of Ω for short O is characteristic of the epichoric Parian alphabet, and suggests that the scribe himself was of Parian origin; most other Greek scripts would use omicron, instead of omega, to express a short O.

The aggressive nailing, binding, shackling, inscribing, and modulation of the figurine, combined with the mortuary context and abundant parallels, suggest that the object was ritual in nature, implicated as an effigy in a binding curse. The inscribed figurine is the first attestation of binding magic on Paros, and sheds new light on private curse rituals, onomastics, the local Parian script, and notions of sexuality and competition in the Classical Aegean.

How can the study of curse tablets and effigies help us write (and teach) more inclusive histories of the ancient Mediterranean world?

Well, curse tablets in particular document persons who often slip through the cracks of traditional histories, enabling us to approach antiquity through a broader lens: here are cooks, tavern keepers, cumin-sellers, helmsmen, and barbers. These objects enrich our view of the classical past, populating the Greek world with a more inclusive group of narratives than otherwise afforded by literary sources.

Greeks and, later, Romans would spread these ritual technologies to the non-Greek and non-Roman communities with whom they came into contact, so in this sense curse rituals also provide a way of studying the ancient Oscans, Iberians, Carthaginians, and other groups who lived around (and well beyond) the Greek and Roman Mediterranean. These objects provide snapshots of people’s angers and frustrations, sometimes incantatory, sometimes white hot in intensity; they show what individuals were actively seeking after— their hopes, anxieties, aggressions, and fears.

The powerful emotions captured in these objects come down to us deracinated in some ways but intact in others, reminding us that the ancient Greek world was very much awash in conflict, competition, and rites aimed to mitigate vulnerability and loss. Bringing the study of these magical texts and objects within the realm of Classics forces us to readjust our view of the Greeks as, e.g., bastions of “rationality.” As I note in this book, Classical Greek democracy, philosophy, medicine, and art— long touted by Western states and individuals as ancestral beacons of poise and rationality— coexisted with curse-writing, spells, and incantations. But a world in which the contemporaries of Socrates, Euripides, Plato, Alexander the Great, the Ptolemies, Hannibal, Julius Caesar, Jesus Christ, Marcus Aurelius, and Constantine all engaged in curse rituals makes for a far more complex, realistic, and interesting history of Classical antiquity than would be the case otherwise.

Additional Resources

See further resources on ancient magic here here.

Projects by Author referred to in this post:

Lamont, Jessica. 2023. “Magic in Ancient Greece and Rome .” Anthropology News: https://www.anthropology-news.org/articles/magic-in-ancient-greece-and-rome/

—–. In Blood and Ashes: Curse Tablets and Binding Spells in Ancient Greece. Oxford University Press (2023).

—–. “Classical and Hellenistic Curse Tablets from the Athenian Agora.” Hesperia 92.2 (2023), 311–53. Co-authored with J. Curbera, Inscriptiones Graecae, Berlin.

—–. “Trade, Literacy, and Documentary Histories of the Northern Black Sea.” Journal of Hellenic Studies 143 (2023), 1–23.

—–. “Cosmogonies of the Bound: Titans, Giants, and Early Greek Binding Spells.” Classical Philology 116.4 (2021), 471-97.

—–. “Cursing Theophrastos in Paros.” American Journal of Archaeology 125.2 (2021), 207-222.

—–. “Cold and Worthless: The Role of Lead in Curse Tablets.” TAPA 151.1 (2021), 35-68.

—–. “Crafting Curses in Classical Athens: A New Cache of Hexametric Katadesmoi.” Classical Antiquity 40.1 (2021), 76-117.

—–. “The Curious Case of the Cursed Chicken: A New Binding Ritual from the Athenian Agora.” Hesperia 90.1 (2021), 79-113.

Jessica L. Lamont is an historian, epigraphist, and archaeologist of the ancient Greek world, with research and teaching interests in Greek magic, religion, and medicine. She is an Assistant Professor of Classics and History at Yale University, and the author of In Blood and Ashes: Curse Tablets and Binding Spells in Ancient Greece (2023). You can read more about her scholarship on her university web page. Outside of work, she enjoys exploring Greece on foot and by kayak, in addition to running, skiing, and (attempts at) watercolor-painting.