Peopling the Past brings you an ongoing blog series, “Unknown Peoples”, featuring researchers who investigate understudied and/or marginalized peoples in the past.

The ‘Libyans’ (sometimes referred to as “Africans” or “Berbers”) are the indigenous peoples of the Maghreb: the vast territory stretching across North Africa from modern western Libya, through Tunisia and Algeria, to the Atlantic coast of Morocco, and from the northern Sahara to the Mediterranean coast. Understandings of these diverse groups has always been shaped through forms of colonialism, whether in literary accounts, in modern ethnic ideologies, or in archaeology. Our sources for these peoples are thus deeply problematic; even so, new archaeological and historical work is transforming our understandings of indigenous North African groups in the first millennium BCE.

North African peoples enter written history in the context of ancient geographies and ethnographies. Both were literary genres born from colonial encounters and settlement of the central and western Mediterranean in the first millennium BCE, as Phoenician-speaking immigrants established communities across the North African coast (including at Carthage), and Greek-speakers did the same in Cyrene (modern eastern Libya) and on nearby Sicily. From the mid second century BCE, after Rome defeated Carthage in the Third Punic War (149-146 BCE), the region and its inhabitants gradually fell under Roman control in ways that generated different kinds of textual accounts and archaeological evidence for the peoples of North Africa. Later, in the 14th century CE, Ibn Khaldūn wrote a history of the “Berbers” and the Islamic conquest of North Africa: an account central not only to modern understandings of the region and its peoples, but which solidified imaginations of a “Berber” people distinct from “Arabs.”

And from the French military conquest of Algeria beginning in 1830, the seizure of Tunisia as a French protectorate in 1881, and the creation of French and Italian protectorates in Morocco (1912) and Libya (1911), historical and archaeological research became entangled with (and undergirded) modern racial, nationalistic, and colonial ideologies. Often, these modern accounts stress “Berber permanence” in North Africa from antiquity through modernity: that the indigenous peoples of North Africa were either stubbornly resistant to cultural change and “civilization” by colonial powers (whether Rome or France), or proudly true to an authentic national spirit in spite of waves of colonization. Understanding the peoples of North Africa cannot be done without recognizing the way our sources have been shaped by this colonial history.

Although many of these colonial traditions focus on creating a single, unchanging, ethnic “people” in Africa (“the Berbers”), they also hint at the diversity and fluidity in how the inhabitants of Africa grouped together. In the fifth century BCE, the Greek author Herodotus (4.168-198) dubs these peoples “Libyan” because they live on the continent of Libya: what tied them together was geography alone. Language may have been the strongest tie among these peoples, but even this was a weak link, and left no written records before short, mostly funerary, inscriptions that begin to appear in the late first millennium BCE. Most inhabitants of the Maghreb probably spoke a family of related Afro-Asiatic languages, but there also seem to have been important differences that emerged through migration and settlement in the first millennium BCE; the upland Tell (central Algeria through Tunisia), for example, seems to have developed its own way of speaking by the mid first millennium BCE, distinct from that of groups further south in the Sahara.

Indeed, the inhabitants of North Africa seem to have been marked by a diversity of customs, practices, and lifeways. Herodotus’ Libyans are divided into different ethnoi (people or extended kin groups), ranging from transhumant shepherds to cattle-herders to farmers. As Rome and Carthage became embroiled in a series of conflicts—the Punic Wars—from the mid third century BCE onwards, Graeco-Roman accounts describe the rise of dynastic kings ruling larger political confederations: the Numidians, divided into the Massyli in the upland Tell of eastern Algeria/Tunisia or Masaesyli further west, and the Mauri further west still. Other, larger groupings included the Gaetuli, who seem to have occupied the northern fringe of the Sahara, and the Garamantes around oases in central modern Libya.

Later geographical texts written under the Roman Empire, but drawing on earlier sources, also mention a multitude of populi in Africa; Pliny (HN 5.29) says 516 different African peoples belonged to the Roman Empire (though the set he names differ from Herodotus’ account). Inscriptions from the Roman imperial period that name people-groups preserve only about 100 names of people-groups, and the sixth-century epic poet Corippus, who celebrates Byzantine wars in Africa, lists different groups still. These discrepancies suggest a fluidity in how people-groups might identify themselves (or be identified by outsiders) through history: extended kin-groups might fissure or fuse together for collective action in different circumstances. The practices and lifeways of these groups varied widely—perhaps not surprising, given the very different environmental niches they inhabited, from oases, to the pre-desert, to grassy steppes, to mountains and plateaus, to the Mediterranean coast. While there were some resemblances among the inhabitants of ancient North Africa, their diversity and differentiation emerge clearly in ancient textual sources.

There are significant gaps in our archaeological knowledge of the inhabitants of Africa between the Neolithic period and the first millennium BCE, partially created by colonial legacies. Down to the early third millennium BCE, rock-shelters, dining waste, and stone tools provide evidence for lifeways based on hunting, land-snail collecting, and foraging in the north-central Maghreb (archaeologically shorthanded as the “Capsian culture,” after important finds near the Gafsa oasis in Tunisia). Further south, petroglyphs and archaeological evidence points to a world of primarily transhumant pastoralists and cowherds in the Saharan zone (the “Pastoral Period”). However, across the northern Maghreb, there are almost no archaeological remains datable from the end of the Capsian period (mid third millennium BCE) to the mid first millennium BCE, when Phoenician colonies (and ceramics) appear.

Some of this may be the result of the particular lifeways of Libyan peoples in this period: dispersed settlements, dwellings made of perishable materials (what Latin authors dubbed mappalia), little use of non-perishable materials (metal, stone), and non-monumental ways of disposing of the dead. But this lacuna is also the result of colonial archaeological and historical practices: a disinterest in indigenous pasts that led to privileging excavation at more Classical-looking Phoenician and Roman sites (and rarely below Roman strata), an assumption that indigenous people of the past could be understood simply by observing unchanged modern Berbers, and a dependence on Greek and Phoenician ceramics chronologies (and thus products from the period of Phoenicio-Greek colonization onwards) rather than using radiocarbon dating. Ancient and modern colonialisms have deeply shaped the sources available for understanding the African past.

Recent archaeological work at the site of Althiburos by a Tunisian-Spanish team has shed important new light on African groups in the early-mid first millennium BCE, offering some of the first evidence for settlements and lifeways through detailed and interdisciplinary scientific analysis. Set in the Tunisian Tell, Althiburos became a heavily monumentalized city under the Roman Empire, and its Roman remains had been excavated and studied earlier under the same colonial focus on empire and monumentality that shaped much North African archaeology. The recent excavations looked below parts of a major Roman sanctuary, and found evidence for long-term settlements from at least the beginning of the first millennium BCE, with earthen buildings set atop stone footings. The early occupants of Althiburos engaged in both intensive cattle-rearing and cerealiculture, producing a wide variety of handmade ceramic pots.

Although the site was seemingly abandoned from the early seventh century BCE, it was re-occupied a century later by inhabitants whose lifeways were generally similar, but showed deeper engagement with the Phoenician-speaking communities on the coast. From the fourth century BCE onwards, the excavators note important shifts in the site: a marked increase in pottery imports suggests greater integration into wider Mediterranean social and commercial networks; a new defensive wall speaks to increased urban centralization and perhaps also participation in the conflicts that helped define the period; increases in olive and sheep/goat remains point to changing productive regimes; and the establishment of a new sanctuary where perinatal children could be burned as offerings to the Phoenician deity Baal Hammon via monuments inscribed in the Punic language points to changing cultural practices and ways of grouping together.

Indeed, across the Maghreb, the period when Greek and Latin authors describe the rise of Numidian kingdoms and the decline of Carthaginian hegemony (fourth-first centuries BCE) seems to be one of profound social change driven by the growing entanglement of African communities with the wider Mediterranean. Numidian leaders, like the Massylian king Massinissa, struck coins to facilitate trade (and demonstrate political legitimacy) in the wider Mediterranean; built alliances with other Mediterranean powers (especially Carthage or Rome); and participated in a pan-Mediterranean world of benefaction that earned them honours and statues in Greek sanctuaries, set alongside other Hellenistic kings. Massinissa was also able to send large quantities of surplus grain to wider Mediterranean markets, not only participating in food-diplomacy, but demonstrating significant intensification in North African agriculture in the third-second century BCE.

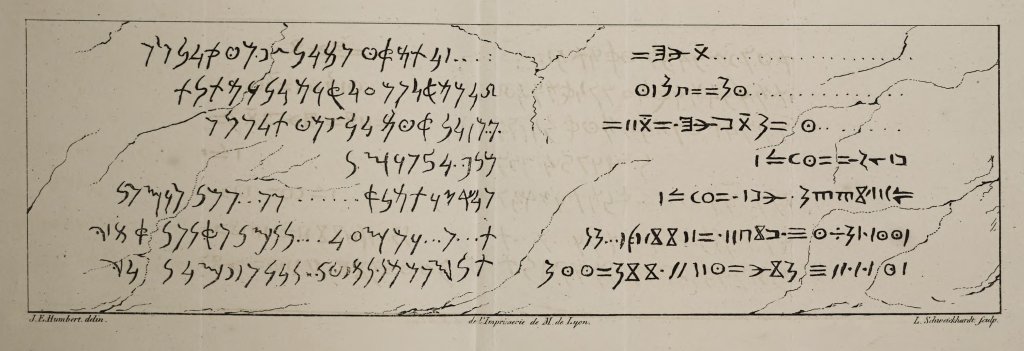

A number of more nucleated and monumentalized urban centers like Althiburos also sprang up across the Maghreb between the fourth and first centuries BCE, speaking to changes in how wealth was generated and displayed. Because many of these towns were also key centers in the Roman imperial period, and acquired even more monumental structures, their pre-imperial histories are rarely recognized. Most hugged natural hills, and were surrounded by fortification walls that suggest large-scale community projects. Wealthy inhabitants of these towns built large, multiroom houses with stone footings, attested at sites like Thugga, Mactar, and Bulla Regia; they probably also controlled local industries like clay harvesting, pottery production, and the quarrying/stoneworking which created this monumental boom. Built sanctuaries also appear, many seemingly built by civic elites and drawing on architectural repertoires from the wider Mediterranean; between the second and first century BCE, at least 3 or 4 temples (including one to the deified Massinissa) were built around a public space at Thugga. There was also a huge increase in carved and inscribed stone monuments, both dedicated to deities in sanctuaries and commemorating the dead. These were inscribed either in the Punic language of Carthage using adapted neo-Punic scripts, or in Libyan, using scripts that may have been developed to manage an increasingly complex set of Numidian kingdoms. Nucleated settlements and urbanism certainly existed before Carthaginian and Roman empires expanded into Africa, but the ways these developed as monumental centers of authority, and the ways that urban elites situated themselves, were always in dialogue with a wider Mediterranean world.

One of the other key archaeological changes in this period seems to be the development of much larger, more visible cemeteries with monumental tombs. In the absence of radiocarbon dating or detailed ceramics analysis, though, many of these tombs are only generally dated; some seem to have been used and re-used for centuries, well into the Roman imperial period. Archaeologists categorize the tombs by typologies: haouanet, tomb-chambers cut into vertical rock faces; dolmens, with tomb chambers built of slabs of rock set vertically; bazinas, which were made of stone-built rings with a tomb-chamber at the center; and other round, mounded tombs. Some of these types were quite widespread: round, mounded tombs were part of a family of funerary practices shared across the Sahara and North Africa, while dolmens seem to have been particularly popular in the Tell regions associated with the Massyli. In the fourth through first centuries, tombs became particularly large and monumental; these included the 58.7m-diameter drum-shaped Medracen that dominated the plain south of the “royal city” of Cirta, its base built of ashlar with Doric demi-columns that gesture to wider Mediterranean architectural styles. The local elite in growing urban centers across Numidia also built richly-carved tower-tombs like the mausoleum built by Atban on the edge of Thugga, complete with its bilingual Punic-Libyan inscription, pointing to the rise of powerful individuals able to harness labour, raw materials, and symbolic capital.

Far from “Berber permanence,” the diverse peoples of North Africa experienced a number of social, cultural, and economic changes over the first millennium BCE, catalyzed by their engagement with other Mediterranean peoples and political powers. Recent archaeological work is begging to tell that story, but more concerted and scientific efforts to understand the lifeways, practices, and histories of indigenous Africans is needed to overcome the stubborn colonialism baked into North African studies.

Additional Reading

Aounallah, S. and Brouquier-Reddé, V. (eds). 2020. “Dossier « Dougga, la périphérie nord (résultats des campagnes 2017-2019) ».” Antiquités africaines 56, 175-273.

Ardeneleanu, S. 2021. Numidia Romana? Die Auswirkungen der römischen Präsenz in Numidien (2. Jh. v. Chr.–1. Jh. n. Chr.). Wiesbaden: Reichert Verlag.

Kallala, N. and Sanmartí, J. (eds). 2011-2018. Althiburos I-III. Tarragona: University of Barcelona.

Mattingly, D.J. 2023. Between Sahara & Sea. Africa in the Roman Empire. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Sanmartí, J. et al. 2012. “Filling Gaps in the Protohistory of the Eastern Maghreb: The Althiburos Archaeological Project (El Kef, Tunisia).” Journal of African Archaeology 10(1), 21-44. https://doi.org/10.3213/2191-5784-10213

Matthew McCarty is Assistant Professor of Roman Archaeology at the University of British Columbia. His research focuses on peoples and practices at the margins of the Roman Empire, especially in Africa and in Dacia, where he currently directs the Apulum Roman Villa Project. His forthcoming book, Signs of Empire: Votive Stelae, Traditions, and the Making of Roman Africa explores how Roman imperialism transformed pre-Roman worship practices in the Maghreb. He has authored numerous articles and chapters on the archaeology, history and historiography of ancient North Africa, many of which can be accessed via his Academia.edu page. [link: https://ubc.academia.edu/MatthewMcCarty].

One thought on “Blog #92: The Libyans with Matthew McCarty”