You are currently working on Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s new Egypt on the Nile project; can you tell us a little more about this?

The Carnegie Museum of Natural History (CMNH) first began to display Egyptian material in 1907, although its first exhibition dedicated solely to ancient Egypt only opened in 1990. In 2016, then curator Erin Peters envisioned a new visitor experience, centered on our mission as a natural history museum. Two new directors and one new mission later, Egypt on the Nile is on track to help us “deepen wonder and advance understanding of our natural world—past and present—in order to embrace responsibility for our collective future.” I was hired in 2020 to further develop and complete the project. Egypt on the Nile invites us to explore how human relationships with the Nile River and surrounding landscapes formed the foundation of ancient Egyptian thought and practices. As a natural history museum, we can bring together material culture, natural science specimens, and knowledge from our team of scientists and researchers to challenge familiar narratives that often focus exclusively on death and the afterlife. Instead, this exhibition invites visitors to discover how life in ancient Egypt was influenced by and sustained through the Nile River ecosystem. The significance of river life also has important connections to our local audiences in Pittsburgh, a city that is located at the confluence of the Allegheny, Monongahela, and Ohio rivers (Figure 1).

CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Are there mummified remains in your collection? How did they get there; and have they ever been on display?

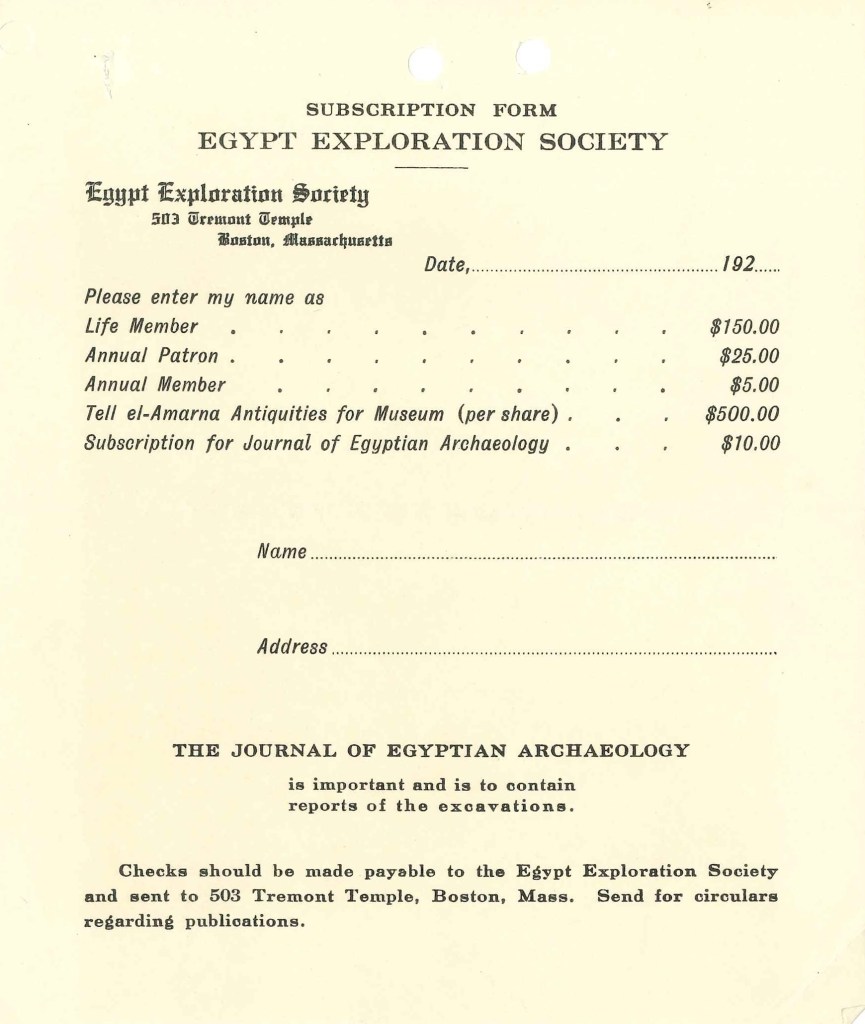

In 1896, Andrew Carnegie established the museum with the gift of the mummified remains and coffin of an unnamed Egyptian woman with the title, Chantress of Amun, which Carnegie purchased on a trip to Egypt. All of the people and objects in our care were acquired by one of two means—through the museum’s subscription to the Egypt Exploration Society (EES) or as a result of purchases made by wealthy individuals in the late 1800s and early 1900s, who then gave or sold those items to the museum. Amelia Edwards founded the British-run EES in 1882. At the same time, Great Britain began a decades-long military occupation of Egypt—significantly increasing the power of the British government and allowing the EES and others to extract and export Egyptian objects and mummified human remains around the world. Dr. William J. Holland, CMNH’s first long-term director, founded the Pittsburgh Chapter of the EES to increase the museum’s holdings and compete with other leading institutions. Based on its financial contributions between 1899 and 1923, the museum acquired the human remains of one ancient Egyptian individual, seven mummified animals, and 1,125 objects (Figure 2). The museum also stewards the remains of additional 16 Egyptian individuals and 30 mummified animals, including cats, ibises, falcons, fish, dogs, and crocodiles, which they acquired through purchases and donations.

Figure 2. Blank subscription form for the Pittsburgh Chapter of the EES. This form references EES excavations at the site of Tell el-Amarna. Courtesy of Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

The museum has displayed mummified human and animal remains from ancient Egypt as well as non-mummified animal remains from other regions and periods around the world, since its founding (Figure 3 ). The former ancient Egypt gallery (open from 1990–2023) displayed three people and seven mummified animals. However, a new policy on the display of human remains was adopted in 2023 and prevents the display of human remains without informed consent. As a result, there are no longer any human remains on display in the museum.

Since you are currently in the process of designing a new hall focused on ancient Egypt, can you, in your capacity as curator, walk us through some of the challenges you are grappling with respect to the ethical implications of displaying mummified human remains?

One challenge is getting everyone not only on board with display changes and why, but excited about them as well, especially when many other museums continue to display mummified human remains. My own journey into thinking more deeply about this began after watching the Everyday Orientalism workshop, Your Mummies, Their Ancestors? Caring for and About Ancient Egyptian Human Remains. It really changed the way I thought about the mummified human remains that I had seen in museums. One thing we discovered very early is that people, especially museum visitors, need clear and transparent information relating to these changes in policy as well as processing time to shift their thinking around long-standing practices and expectations around exhibits on ancient Egypt. This shift in mindset can be especially difficult for modern visitors, since most museum displays on ancient Egypt—historically and currently—include mummified human remains. In many ways, mummified human remains have become intrinsically linked with how the public understands and engages with ancient Egypt. It takes time and new perspectives for visitors to the museum to change those expectations.

What has the process of reimagining the display of mummified human remains looked like for the Carnegie Museum of Natural History?

The first thing that I did was to spend time researching what ancient Egyptian texts and traditions tell us about how Egyptians wanted people to engage with them after death. Then, I developed new terminology for museum staff and a training module for anyone who engages with visitors. We didn’t want the exhibition to shy away from the topic of death, but we also wanted to ensure that we centered ancient Egyptian perspectives, respecting the dignity and ancestral customs of the deceased individuals in our care. To do this, the final section of the new exhibit will explore how beliefs and traditions related to death were rooted in the ecology of the Nile River Valley. It examines the power of burial within the sacred landscape of the Egyptian desert and reflects on what it might mean when people are removed from that burial context. This discussion will be facilitated through the display of the coffin of Natjukhonsurudj (which was purchased without its owner), allowing us to discuss how ancient Egyptian individuals were brought to the museum and why CMNH no longer displays them (Figure 4).

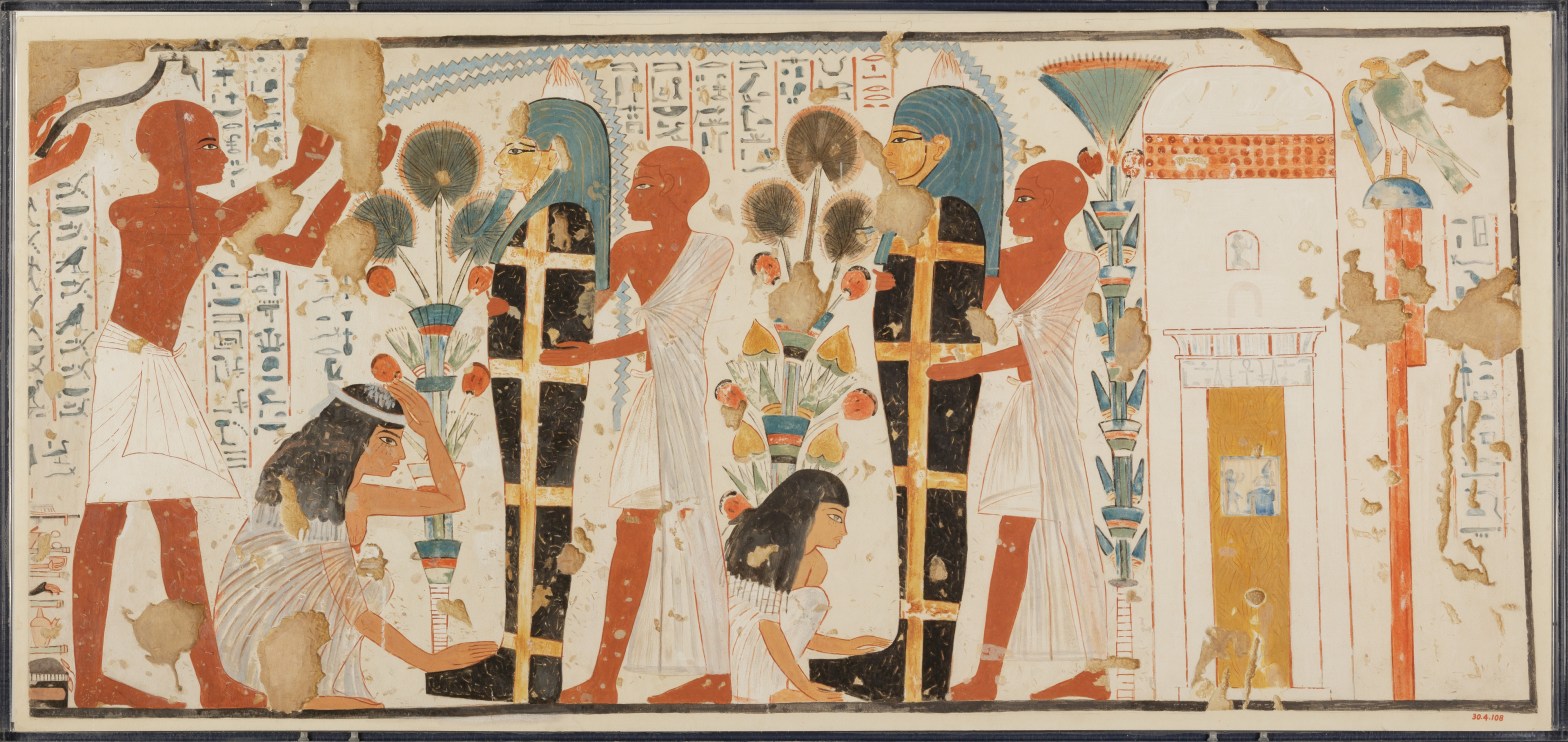

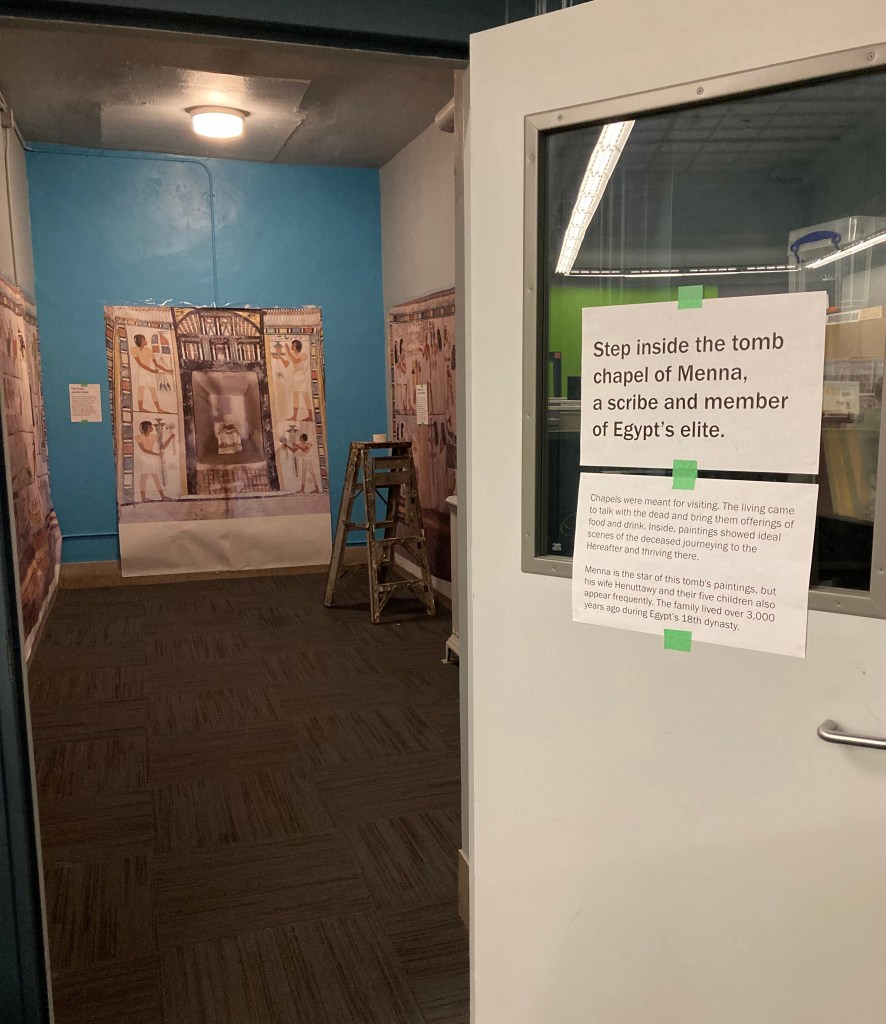

In addition, visitors will learn how ancient Egyptians interacted with the deceased, while simultaneously having the opportunity to do so themselves in an immersive interactive experience centered on a portion of the 18th Dynasty tomb chapel of Menna, a scribe buried in the Theban necropolis. As visitors enter Menna’s tomb chapel, they will learn that these spaces were meant for visiting—they were places where the living came to talk with the dead and bring them offerings of food and drink. Inside, they will be able to see and engage with the tomb’s paintings. In the chapel’s offering area, visitors will be able to touch details in the paintings to trigger animations that further unpack Menna’s wishes and needs in the Hereafter.

In what ways can inclusive and honest representations of ancient Egypt and its peoples change a visitor’s perception of the past? What do you hope visitors to the new Egypt on the Nile hall take away from their experience?

We hope that visitors understand that objects can tell many stories. They can speak to when they were created, when they were excavated/purchased/looted/etc., different phases of research/treatment/or display, and how we are engaging with them now. Those stories reflect changing values and ethics and illustrate how scientific understandings of ancient Egypt transform and adapt as we learn more about the ancient world. There isn’t one way to think about ancient Egypt and restricting its presentation to a few expected topics limits peoples’ abilities to connect with and appreciate past peoples on a deeper, more meaningful level.

During early prototyping for our tomb of Menna experience, for example, we tested different prompts with educators from Carnegie Museum of Art (Figure 5). As we discussed the “Beautiful Feast of the Valley” and the offering area inside Menna’s chapel, one of the educators made an immediate connection to Day of the Dead celebrations and altars in Mexican tradition. We hope that moving the focus from looking at human remains to connecting with ancient Egyptian people, practices, and ideas will enable visitors to form personal connections and see ancient Egyptians as real and complex individuals, not as a kind of ancient and mysterious “other”. Furthermore, we hope that the exhibit will allow our visitors to engage with lesser-known ancient traditions and stories, while simultaneously highlighting the diversity of the human experience, as well as the creativity and ingenuity of the ancient Egyptian people.

Additional Resources

Abd El Gawad, Heba and Alice Stevenson. “Egyptian Mummified Remains: Communities of Descent and Practice.” In: Biers, Trisha and Katie Stringer Clary (eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Museums, Heritage and Death, 238-258. Routledge: Abingdon, UK. 2024.

Baber, Tessa T. “Ancient Corpses as Curiosities: Mummymania in the Age of Early Travel.” Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections 8 (2016): 60–92.

Borromeo, Gina and MJ Robinson. “Care Across Cultures: Shifting our Approach to a Mummy in our Museum.” In Jen Thum, Carl Walsh, Lissette Jiménez, and Lisa Saladino Haney (eds.), Teaching Ancient Egypt in Museums: Pedagogies in Practice. London: Routledge, 2024.

Cannon, Aubrey. “Spatial Narratives of Death, Memory, and Transcendence.” In Helaine Silverman and David B. Small (eds.), The Space and Place of Death, 191–99. Archaeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association 11. Arlington: American Anthropological Association, 2002.

Cassman, Vicki, Nancy Odegaard, and Joseph Powell, eds. Human Remains: Guide for Museums and Academic Institutions. Lanham: Altamira Press, 2007.

Clegg, Margaret. Human Remains: Curation, Reburial and Repatriation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020.

Excell, Karen. “Covering the Mummies at the Manchester Museum. A Discussion of Authority, Authorship, and Agendas in the Human Remains Debate.” In Howard Williams and Melanie Giles (eds.), Archaeologists and the Dead: Mortuary Archaeology in Contemporary Society, 233–50. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Gangewere, Robert J. Palace of Culture: Andrew Carnegie’s Museums and Library in Pittsburgh. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2011.

Haney, Lisa S. “Spatial Narratives of Death: From Egypt to the Museum.” In Tara Prakash, Jennifer Miyuki Babcock, and Lisa Saladino Haney (eds.), Rethinking Ancient Egypt: Studies in Honor of Ann Macy Roth, 137-153. Harvard Egyptological Studies Series 22, Brill. 2025.

MacDonald, Sally and Michael Rice, eds. Consuming Ancient Egypt. London: UCL Press, 2003.

Marstine, Janet, ed. The Routledge Companion to Museum Ethics: Redefining Ethics for the Twenty-First Century Museum. London: Routledge, 2011.

Stevenson, Alice. Egyptian Archaeology and the Museum. Oxford Handbooks Online, 2014.

Stevenson, Alice. Scattered Finds: Archaeology, Egyptology and Museums. London, 2019.

Stienne, Angela. Mummified: The Stories Behind Egyptian Mummies in Museums. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2022.

Swain, Hedley. “Museum Practice and the Display of Human Remains.” In by Howard Williams and Melanie Giles (eds.), Archaeologists and the Dead: Mortuary Archaeology in Contemporary Society, 169–83. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Everyday Orientalism. #EOTalks 4: Your Mummies, Their Ancestors? Caring for and About Ancient Egyptian Human Remains. Organized by Charlotte Parent, Heba Abd El Gawad, and Katherine Blouin.

Pitt Rivers Museum. Human Remains in the Pitt Rivers Museum.

Peopling the Past. Blog Post #19: Peopling the Past’s Approach to the Study and Display Human Remains.

Dr. Lisa Saladino Haney is Curator of Egyptology at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History and a part-time instructor at the University of Pittsburgh. Lisa obtained her masters in Ancient Near Eastern and Egyptian Studies with a concentration in Museum Studies from New York University, and her PhD in Egyptology from the University of Pennsylvania. She’s currently working on the museum’s new long-term hall focused on ancient Egypt, Egypt on the Nile. Her research interests include the visual representation of kingship in Egypt, as well as trade and connections between Egypt and the western Asia in antiquity. She’s written on museum pedagogy and the display of Egyptian artifacts and heritage in museums, including her most recent edited volume Teaching Ancient Egypt in Museums: Pedagogies in Practice (2024).

Like our content? Consider donating to Peopling the Past. 100% of all proceeds support honoraria to pay the graduate students and contingent scholars who contribute to the project.

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is appreciated. Please note that we cannot provide tax receipts, as we are not a registered charity.

Your contribution is appreciated. Please note that we cannot provide tax receipts, as we are not a registered charity.

Your contribution is appreciated. Please note that we cannot provide tax receipts, as we are not a registered charity.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearly