For Halloween month, our blog posts focus on the theme “Cursing in the Ancient World”. Our authors explore the notorious practices of curse tablets and other magical spells, and reflect on the deeper human tendencies that underpin these acts.

In 2013, as an undergraduate student in Classics eager to pursue my studies, I was talking with the professor who would later become my master’s and PhD supervisor about potential research topics. I was interested in religious traditions and practices in the ancient world, especially Egypt, but I had trouble deciding on a specific topic. At some point, he said: “What about magic?” And that’s where it all began for me. Since then, I have been working on magical texts and practices in Late Antique (4th–7th centuries CE) and medieval Egypt (up to the 13th century CE). I am particularly interested in the transmission of magical knowledge across time and space, and the changes and continuities in magical practices after Christianity became the dominant religion in Late Antiquity.

Since 2021, as part of the APOCRYPHA project at the University of Oslo, I have been looking into the relationship between Coptic magical texts and Christian apocryphal literature preserved in Coptic. Within the project, we define apocrypha as “texts and traditions that elaborate or expand upon the biblical storyworld”, or, put more simply through a modern analogy, as Bible “fanfiction”. Incidentally, magical texts and apocrypha have much in common. For example, they were produced and used in similar contexts; many apocryphal works describe magical practices; magical texts often include passages or references to apocryphal works; and both apocrypha and magical texts and practices relate to lived religion.

Magic as Lived Religion

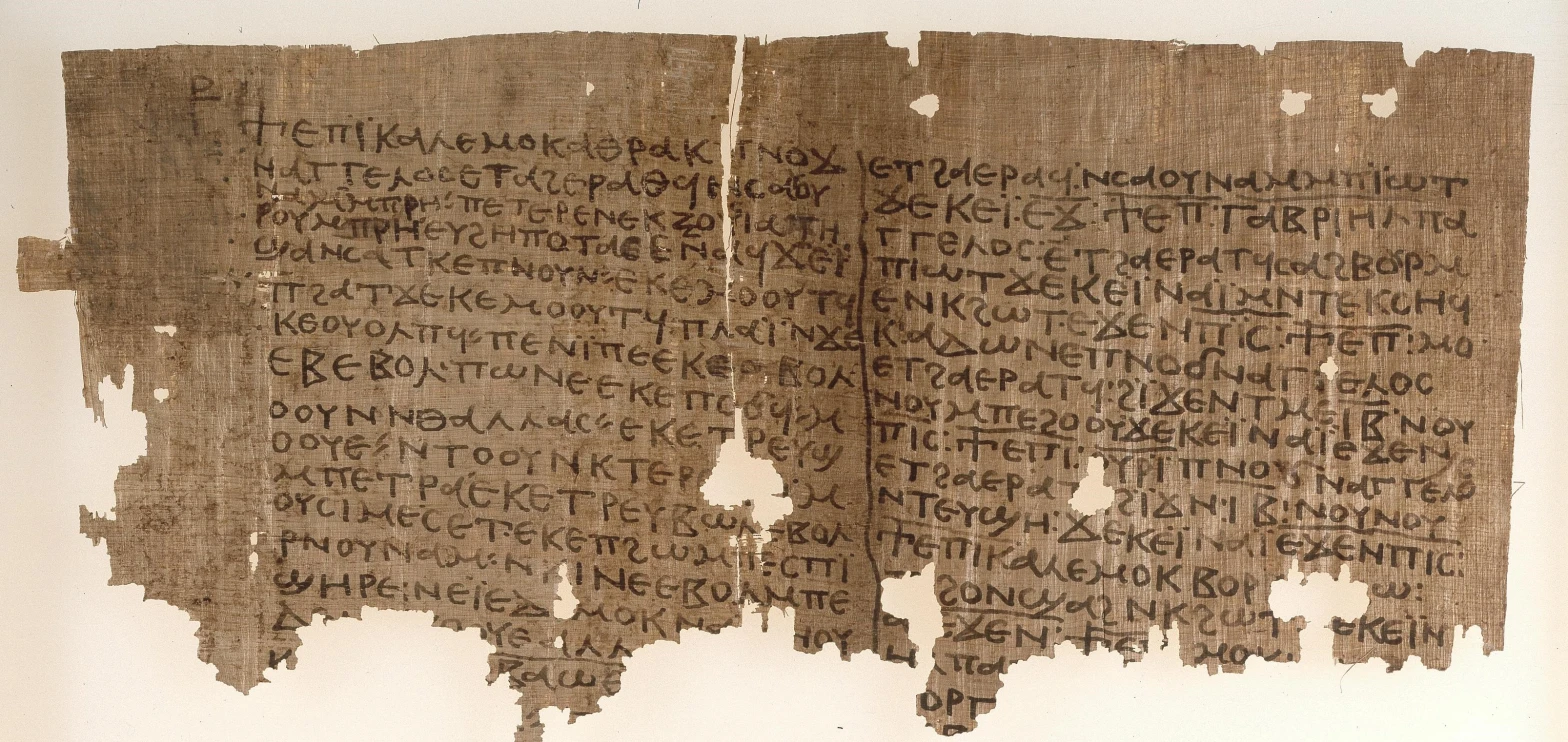

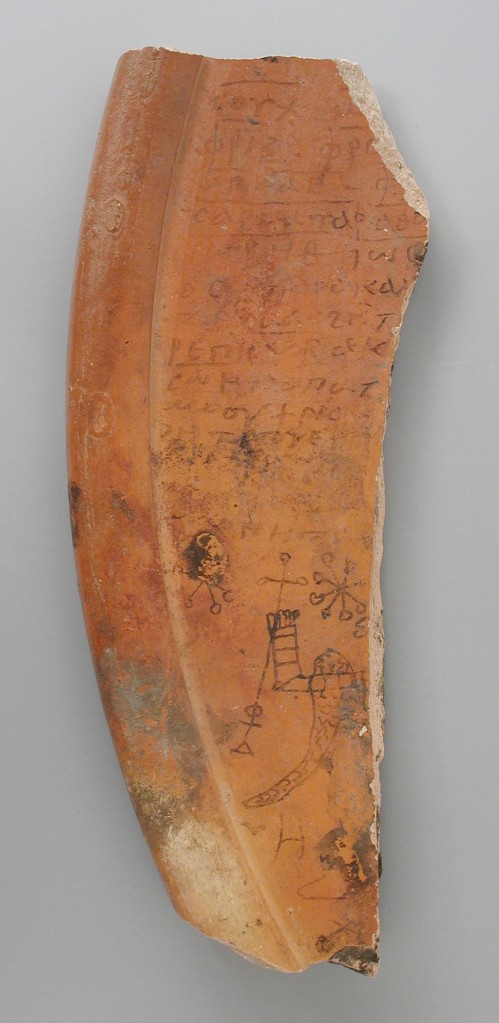

In Egypt, from the Pharaonic times to the Medieval period, magic has been part of how ordinary people experienced religion in their day-to-day lives. By magic, I mean certain ritual practices: the use of incantations (spoken or written down) and ritual actions to appeal to supernatural entities or higher powers and attain specific goals. These practices are witnessed by a wide range of artefacts: objects produced or used during the rituals (such as clay pots and wax figurines [Fig. 1]) and magical texts written on various media, such as papyrus, parchment, paper, leather, metal (lead, silver, gold), ostraca (limestone flakes or pottery sherds [Fig. 2]), or even bones. Magical texts from Egypt have survived in different languages and scripts, including Hieratic (middle Egyptian), Demotic, Latin, Greek, and, from Late Antiquity onwards, Coptic, which refers to the latest stage of the ancient Egyptian language. In the past ten years, my focus has been to study the large corpus of Coptic magical texts from Egypt, which consists of over 500 artefacts dating from the 4th to the 13th century CE.

What is most fascinating about magical texts is that they tell us a lot about real people, how they lived, their interests, anxieties, and aspirations. These texts, and the objects bearing them, were created for people to deal with daily concerns: healing from various diseases and health conditions, protection against attacks from dangerous animals, demons, and other enemies (and how to retaliate), and success in various situations, whether in business, sports competitions, or love affairs, which was often obtained by cursing one’s opponent (or love interest). In addition, magical texts from Late Antiquity are witnesses to the processes of religious transformation that occurred in that period, with the gradual integration of Christianity into society and all its domains. Christians perpetuated magical practices that had existed in Egypt for millennia but adapted them to make them their own, for example, by appealing to Christian entities such as Christ, the Virgin Mary, saints, and angels, or by quoting passages from canonical and apocryphal scriptures in their magical texts. In some cases, we even see texts that combine Christian material and elements from the Greek and Egyptian traditions, for example, references to deities or mythological episodes.

Love Spells in Coptic Magic

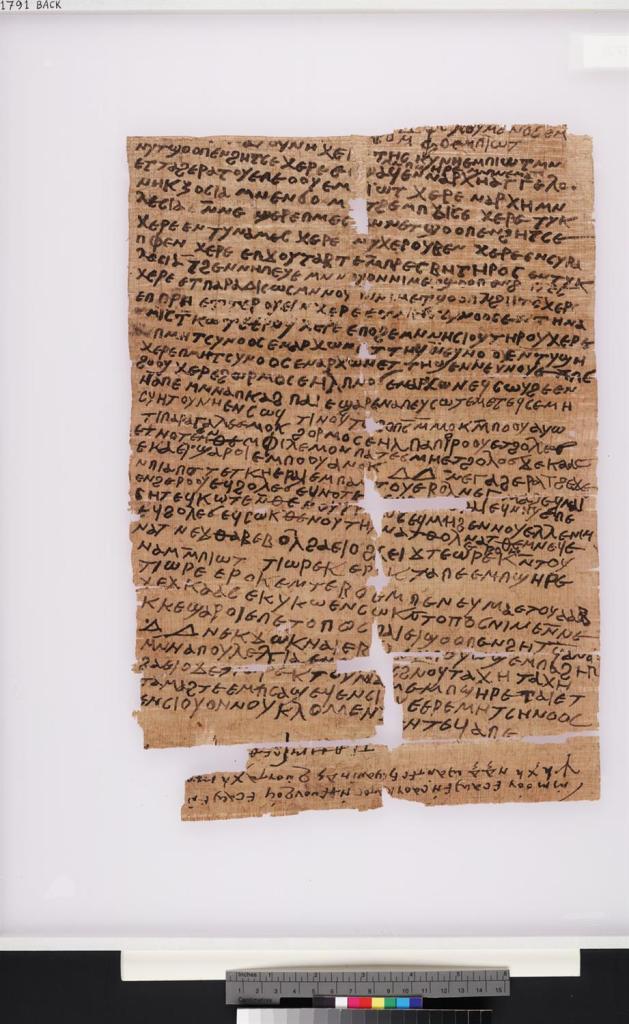

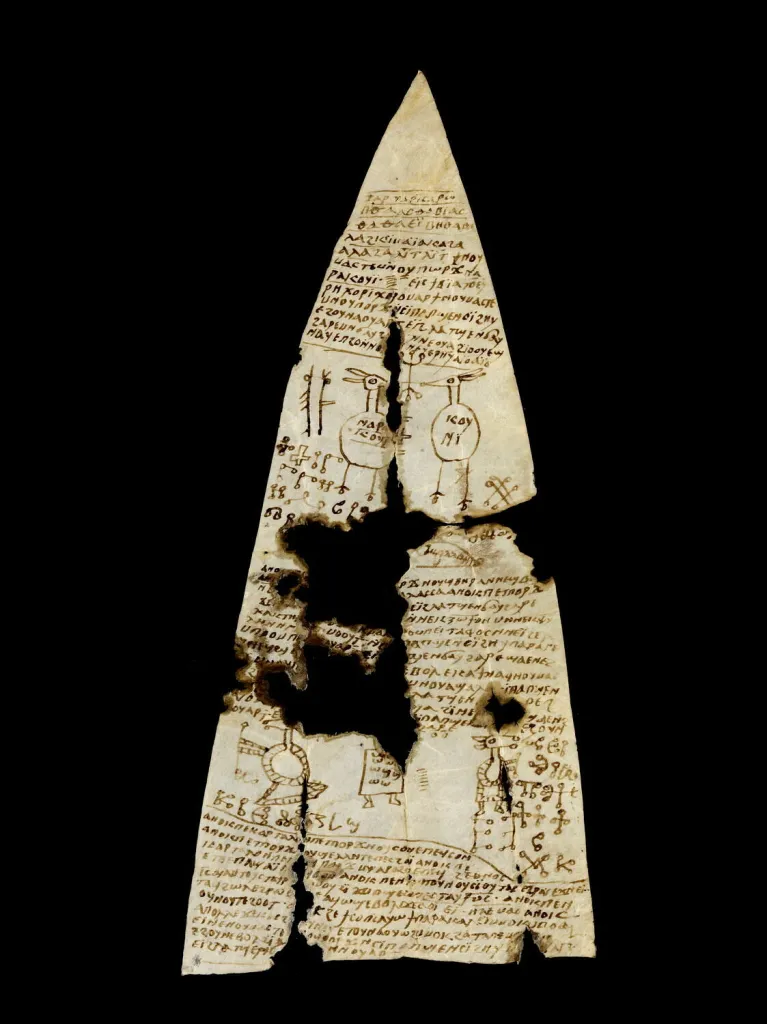

While healing and protection are the most represented goals within the corpus of Coptic magical texts, a fair number of texts and rituals were intended for manipulating relationships. From these, love spells are the most frequent and were meant to force “love” onto another person, either an unreceptive love interest or an unfaithful partner. A common technique used in love spells was to ask the powers or entities invoked to prevent the target from eating, drinking, or sleeping until they yielded [Fig. 3]. Conversely, separation spells aimed at destroying existing couples were used by jealous suitors or disapproving parents. Some artefacts bearing separation spells were even shaped in the form of a blade so that they could literally sever the relationship [Fig. 4]. Other related rituals included virginity spells and curses against virility, meant to prevent people from having sexual intercourse. The number and variety of these spells, as well as the ingenuity and creativity used while composing the texts and creating the objects, show how these relationships occupied a central place in the life of people in Late Antique and Medieval Egypt.

One of my favorite examples is from a text I studied for my doctoral dissertation. It is a Coptic love spell written on a piece of parchment, dated approximately to the 6th–7th centuries CE [Fig. 5]. The spell was probably used as a template to be copied down or recited aloud on different occasions by a ritual expert, as it contains the generic markers “NN” that were meant to be replaced with the names of eventual recipients and targets. In the first part of the spell, the recipient (that is, the person using the spell) calls upon holy oil, Iao Sabaoth, as well as the Egyptian deities Isis and Osiris, so that the intended target would grow to love them:

“O holy oil! O oil which flows from beneath the throne of Iao Sabaoth! O oil with which Isis anointed the bones of Osiris! I call to you, O oil […] so that you will bring NN to me—I, NN—and you will cause my love to be in her heart, and hers to be in mine, like a brother and a sister, and a she-bear who wants to suckle her offspring, yea yea!”

Here, the spell makes a clear reference to the myth of the mummification (including the anointing of the bones) of Osiris by his sister-wife Isis, with the hope that the love uniting Isis and Osiris would be replicated between the recipient and the target. The second part of the spell is set in Hell, with the Devil and Temelouchos, the angel of divine punishment known from Christian apocryphal literature (such as the Apocalypse of Paul, the Apocalypse of Peter, the Questions of Bartholomew, and the Book of Thomas):

“No, my lord, do not hand me over to Temelouchos, he who is set over the judgment, rather I want you to go down to Hell and tear out all the thoughts of the Devil concerning NN, the child of NN, and for you to cause my love to be in her heart and hers in mine, for it is I who calls, and it is you who does the desire.”

(For the full translation, see K. Dosoo, E.O.D. Love, and M. Preininger [chief editors], with R. Bélanger Sarrazin, “KYP T343: Love spell invoking oil”, Kyprianos Database of Ancient Ritual Texts and Objects, https://www.coptic-magic.phil.uni-wuerzburg.de/index.php/text/kyp-t-343/)

In crafting this love spell, the author decided to combine references to an ancient Egyptian myth and Christian entities in a unique and innovative way to achieve the desired outcome: that the target loves the recipient. This magical text therefore represents a vivid example of how people from Late Antique and medieval Egypt used elements from the various religious traditions with which they were in contact to create powerful spells that would allow them to navigate the trials and tribulations of their daily lives and, ultimately, how they reacted and adapted to their cultural and religious contexts in transformation.

Additional Resources

R. Bélanger Sarrazin, Les divinités gréco-égyptiennes dans les textes magiques coptes: Une étude du syncrétisme religieux en Égypte tardo-antique et médiévale (Leuven: Peeters, forthcoming) (Revised PhD dissertation).

—, “Catalogue des textes magiques coptes,” Archiv für Papyrusforschung und verwandte Gebiete 63 (2017) 367–408.

K. Dosoo and M. Preininger (eds.), with R. Bélanger Sarrazin, E.O.D. Love, S. Schuster, and J. Schwarzer, Papyri Copticae Magicae. Coptic Magical Texts, Volume 1: Formularies. (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2023).

D. Frankfurter, “The Perils of Love: Magic and Countermagic in Coptic Egypt.” Journal of the History of Sexuality 10 (2001) 480–500.

K. Hevesi, “A Few Remarks on the Persistence of Native Egyptian Historiolae in Coptic Magical Texts,” in M. Peterková Hlouchová, D. Belohoubková, J. Honzl and V. Nováková (eds.), Current Research in Egyptology 2018: Proceedings of the Nineteenth Annual Symposium, Czech Institute of Egyptology, Faculty of Arts, Charles University, Prague, 25-28 June 2018 (Oxford: Archaeopress Publishing, 2019) 42–54.

H. Lundhaug, “Textual Fluidity and Monastic Fanfiction: The Case of the Investiture of the Archangel Michael in Coptic Egypt,” in I.S. Gilhus, A. Tsakos, and M.C. Wright (eds.), The Archangel Michael in Africa: History, Cult, and Persona (London:Bloomsbury Academic, 2019) 59–73.

M.W. Meyer, and R. Smith. Ancient Christian Magic: Coptic Texts of Ritual Power. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1999).

J.-M. Rosenstiehl, “Tartarouchos-Temelouchos. Contribution à l’étude de l’Apocalypse apocryphe de Paul,” in J.-M. Rosenstiehl (ed.), Deuxième journée d’études coptes (Leuven: Peeters, 1986) 29–56.

S.J. Shoemaker, “Early Christian Apocryphal Literature,” in S.A. Harvey and D.G. Hunter (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Early Christian Studies (Oxford: Oxford University Press) 521–548.

J. van der Vliet, “Magic in Late Antique and Early Medieval Egypt,” in G. Gabra (ed.), Coptic Civilization: Two Thousand Years of Christianity in Egypt (Cairo – New York: American University in Cairo Press, 2014) 145–152.

—, “Tradition and Innovation: Writing Magic in Christian Egypt,” in N.M. Vos and A.C. Geljon (eds.), Rituals in Early Christianity: New Perspectives on Tradition and Transformation (Leiden: Brill, 2020) 262–281.

W.H. Worrell, “Coptic Magical and Medical Texts.” Orientalia, NOVA SERIES 4 (1935) 1–37 and 184–194.

Online resources

Roxanne Bélanger Sarrazin is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Oslo with the ERC-funded project Storyworlds in Transition: Coptic Apocrypha in Changing Contexts in the Byzantine and Early Islamic Periods (APOCRYPHA). Within this project, she works on the relationship between Coptic apocrypha, magic, and liturgical practices. She is also a member of the Philae Temple Graffiti Project (PTGP), funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC), and a contributor to the project Coptic Magical Papyri: Vernacular Religion in Late Roman and Early Islamic Egypt. Bélanger Sarrazin has a Ph.D. in Religious Studies and in Languages, Literatures, and Translation Studies from the University of Ottawa (Canada) and the Université libre de Bruxelles (ULB, Belgium). Her first monograph, Les divinités gréco-égyptiennes dans les textes magiques coptes: Une étude du syncrétisme religieux en Égypte tardo-antique et médiévale (Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta; Leuven: Peeters, forthcoming), is set to appear shortly.