One of Peopling the Past’s goals is to amplify the work of young and/or under-represented scholars and the amazing research that they are doing to add new perspectives to the fields of ancient history and archaeology (broadly construed). We will thus feature several blog posts throughout the year interviewing graduate students on their research topics, focusing on how they shed light on real people in the past.

Peopling the Past brings you an ongoing blog series, “Unknown Peoples”, featuring researchers who investigate understudied and/or marginalized peoples in the past.

What topic do you research?

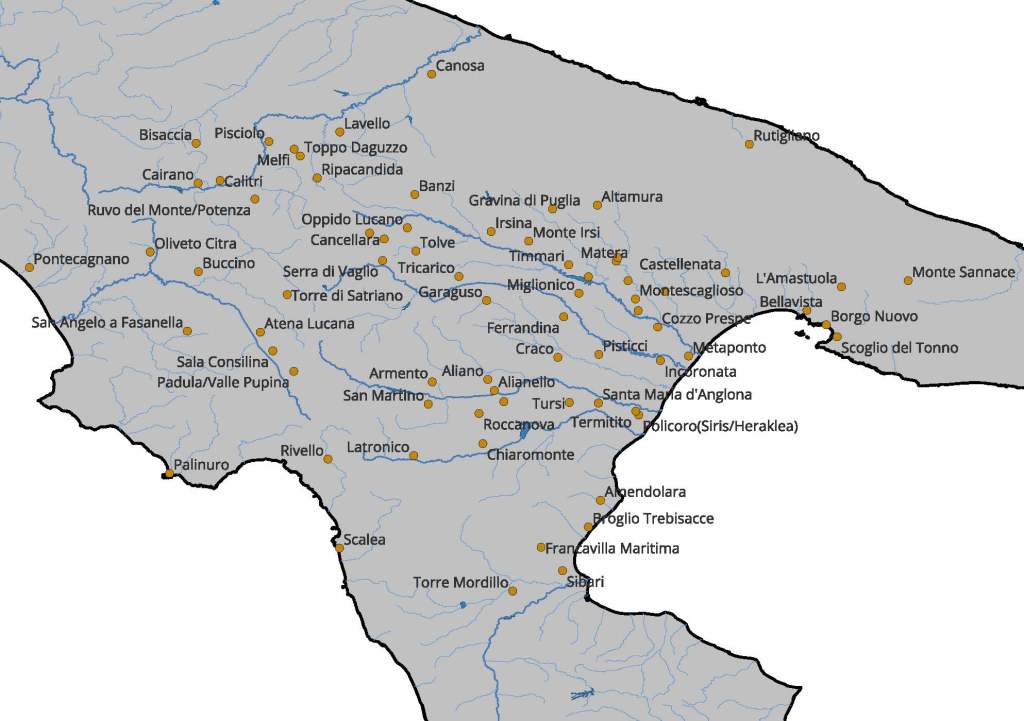

Broadly, the topic of my research is the archaeology of Basilicata, Italy (in the instep of the boot), during the Iron Age. Several different groups inhabited the region at the time, but I focus on a group known as the Oenotrians (sometimes spelled Enotrians, and sometimes also referred to as ‘Chaones’). The Oenotrians are the first peoples encountered by the Greek settlers arrived and founded cities including Metaponto, Siris, and Sybaris in the 8th and 7th centuries BCE.

While we have a few ancient sources that describe the regions various Italic tribes of Southern Italy inhabited, such as Aristotle, Strabo, and Dionysius of Halicarnassus, they offer little useful historical data. The descriptions of the Oenotrians are vague and descriptions of their origins are quasi-mythical and legendary. This makes it difficult to reconstruct the social organization, religious practices, or the nature of interaction within and between the indigenous Italic populations of Southern Italy, including the Oentorians.

To address this gap in our understanding, my research focuses on using archaeological data from Italic sites in Basilicata to conduct a network analysis. This analysis aims to trace interactions between Oenotrian communities by examining the composition and deposition of archaeological assemblages across the region. I am constructing separate networks for the prehistoric Early (ca. 1000 to 720 BCE) and Late (ca. 720 to 580 BCE) phases of the Iron Age to explore how trends change over time. Using the results, I aim to develop a narrative on the relationships between Oenotrian communities.

What sources or data do you use?

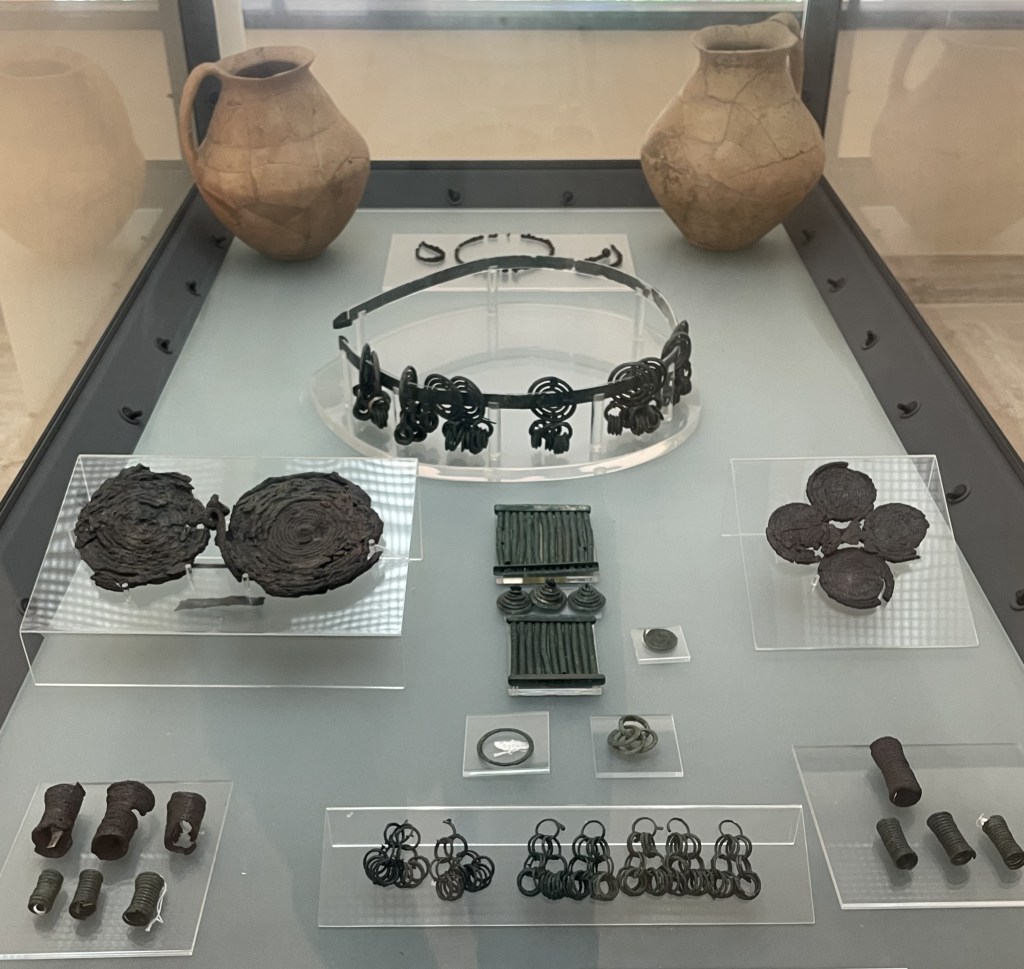

The two types of artifacts I use in my network analysis are locally made geometric Matt Painted Pottery (MPP) and metal fibulae. MPP is an Italic ceramic tradition found at Southern Italian sites from the Late Bronze Age through the Archaic and, in some cases, into the Hellenistic period. Since it is distinct from locally produced, coarser impasto wares and from imported Greek pottery, it is a key identifier of indigenous sites in Basilicata. The typology and chronology of this pottery, developed by scholars like Douwe Yntema and Edward Herring, has been crucial for studying trade, exchange, and mobility in Southern Italy.

Fibulae, on the other hand, are essentially brooches or pins, typically made of bronze, used to affix clothing. They have been in use since the Early Bronze Age and are found in many different styles in Oenotrian contexts. By comparing assemblages of both MPP and fibulae that are most closely associated with the Oenotrians from sites across Southern Italy in a network analysis, I hope to be able to visualize and characterize how indigenous communities of Southern Italy interacted with each other.

How does this research shed light on real people in the past?

The term ‘Oenotria’ was applied by Greek settlers to describe all of Italy, but came to eventually to describe a specific group believed to inhabit what is today the region of Basilicata. The etymology of the name is uncertain, but it has been variously linked by scholars, ancient and modern, to the Greek word ‘oinos,’ meaning ‘wine,’ and to the name of a mythological founder from Greece named Oenotros. What this Iron Age population called themselves remains ultimately unknown, but what is perhaps more troubling is that we know very little about the lives of the Iron Age Italic people it describes.

Oenotrians have often been studied in relation to the Greek colonies, which have received more detailed attention from historical and archaeological sources. Although scholarship over the last 40 years has focused more on the indigenous populations of Italy, there have been few attempts to synthesize the available data due to its long chronological range and wide geographical spread. My research aims to aggregate data from over 70 sites in Southern Italy to begin reconstructing the relationships between Oenotrian communities. By analyzing the interaction between these communities through their grave assemblages, I hope to illuminate not only the lived experience of Oenotrians, but also, at least in part, their history.

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank UBC for hosting the Connect Past Conference for 2024. It’s exciting to be able to present my work to scholars using similar methods and techniques for investigating the past. I am also grateful to Professor Megan Daniels for inviting me to write this blog post to highlight my research.

Sources and Further Reading

Attema, P., Burgers, G. J. and van Leusen, M. (2018) Regional Pathways to Complexity: Settlement and Land-Use Dynamics in Early Italy from the Bronze Age to the Republican Period. Amserdam University Press.

Battiloro, I. (2017). The Archaeology of Lucanian Cult Places: Fourth Century BC to the Early Imperial Age. Routledge.

Bietti Sestieri, A. M. (2010). L’Italia nell’et`a del bronzo e del ferro: Dalle palafitte a Romolo. Rome: Carocci.

Blake, E. (2014) Social Networks and Regional Identity in Bronze Age Italy. Cambridge University Press

Brughmans, T., Collar, A. Coward, F. (2016). Network Perspectives on the Past: Tackling the Challenges. The connected past: challenges to network studies in archaeology and history. Oxford University Press. 3-20.

Carter, J.C., (2009). Discovering the Greek countryside at Metaponto., Ann Arbor: University of Michigan.

Herring, E. (1998). Explaining Change in the Matt-Painted Pottery of Southern Itay: Cultural and social explanations for ceramic development from the 11th to 4th centuries B.C. BAR International Series 722.

Iacono, F. (2019). The archaeology of Late Bronze Age interaction and mobility at the gates of Europe: people, things and networks around the southern Adriatic Sea. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Lo Schiavo, F. (2010). Le Fibule dell’Italia meridionale e della Sicilia dall’età del bronzo recente al VI secolo a. C. Prähistorische Bronzefunde, Abteilung XIV Band 14, Teile 1–3.

Osanna, M. (2019). Terra Incognita: The Rediscovery of an Italian People with No Name. “L’Erma” di Bretschneider.

Savelli, S. (2016). Models of interaction between Greeks and Indigenous Populations on the Ionian Coast: Contribution from the excavations at Incoronata by the University of Texas at Austin’, in Contextualizing “Early Colonisation”. Archaeology, Sources, Chronology and Interpretative Models between Italy and the Mediterranean, Papers of the Royal Netherlands Institute in Rome, 64, 2016, pp. 371-383.

Yntema, D. (1990). The Matt Painted Pottery of Southern Italy. Congedo Editore.

Yntema, D. (2013). The Archaeology of South-East Italy in the 1st Millennium BC: Greek and Native Societies of Apulia and Lucania between the 10th and the 1st Century BC. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Adrian Talotti Proestos received his undergraduate degree in Archaeology from the University of Toronto in 2016. He earned his MSc in Computational Archaeology at the Institute of Archaeology at University College London in 2017, with his thesis presenting a spatial analysis of Early Medieval English coinage. Currently, he is a PhD candidate at McMaster University in the Department of Greek and Roman Studies. He is also privileged to serve as an Assistant Director of the ongoing Metaponto Archaeological Project, which is currently conducting excavations at the Iron Age site of Incoronata.

One thought on “Blog Post #97: Graduate Student Feature with Adrian Talotti Proestos ”