Peopling the Past brings you our Halloween features on the human skeleton and the deeper stories we can learn about humans from their skeletal remains.

As a bioarchaeologist, my research examines human skeletal remains to try to better understand lived experiences in the past. Predominantly, this research has focused on the lives of adolescents in the Roman Empire and trying to figure out what “adolescence” was really like.

Ancient writers tell us that adolescence (or adulescentia) was a period of hooliganism and debauchery, focused on heavy drinking and sexual encounters. However, these experiences (if accurate), likely only represent the experiences of wealthy teens who could afford this lifestyle. But I wanted to know what adolescence may have been like for middle or lower socioeconomic groups – for those who couldn’t afford to stay out all night drinking and visiting brothels.

To try and figure it out, I looked to their bones. While literary sources can tell us about perceptions or ideas of how adolescence should have been lived, the bones of teenagers can give us more direct insights into the lives they lived, as their experiences become embodied or imprinted on their skeleton.

First, I wanted to know when they physically became adults. So, by looking at different bones in the skeleton (including the bones of the hand, wrist, vertebrae, and pelvis), I determined when puberty occurred in the skeletal samples, finding that boys and girls entered puberty around the same time that we do today. But it appears that in the Roman Empire, puberty was a much longer process than what we experience (three more years of puberty? That’s the really terrifying part).

Then, I wanted to know when these adolescents started to act or behave like adults, so, I looked at what they ate. In the Roman Empire, there were particular ideas about what adults and kids should be eating, as well as what men and women should be eating. At some archaeological sites, we see that these “dietary ideals” are upheld, with males eating more meat and marine resources than females. So, I thought that, by examining changes in diet, we might be able to see when teens were eating like children, and when they were eating like adults, by looking at changes in their diet. Then, by incorporating archaeological, environmental, and literary evidence, I worked to link potential dietary changes to a social age change, from a child to an adult, and even something in between.

Now, you can’t just ask the skeletons what they ate (unfortunately), but we can use dietary stable isotope analysis to begin to understand dietary consumption. This approach is based (very loosely), on the idea: “you are what you eat”. Essentially, as you consume foods, those foods become the literal building blocks of your body, including your bones and your teeth. That means, as bioarchaeologists, we can look at your bones and teeth and start to get an idea of the foods you consumed in life.

Our bones are constantly remodeling, meaning they are always taking up new nutrients and getting rid of old ones. If I were to look at your bones, I’d get a broad idea of your more recent dietary intake (say, the last 15 years or so, depending on the bone). Teeth, however, develop when we’re kids and teenagers, and don’t really change after that. Meaning, if I took a tooth from your mouth, regardless of your age, I could learn about your diet as a kid.

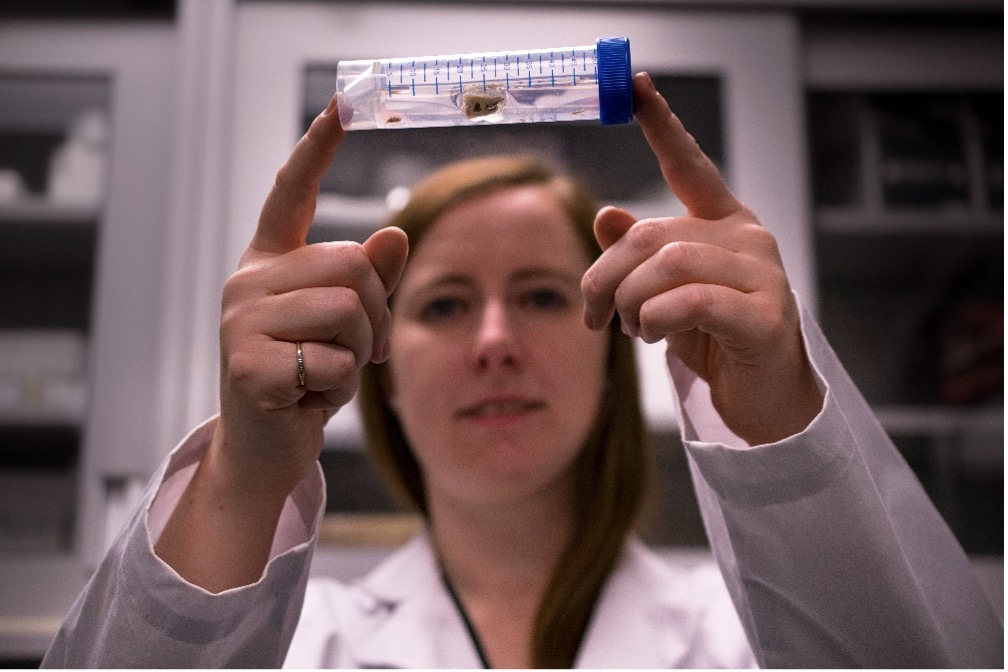

Ultimately, this method involves taking teeth from the mouths of skeletons, travelling through an airport with 150 human teeth (hoping people don’t think you’re a serial killer), and subjecting them (the teeth, not airport people) to destructive analysis in a lab setting. There’s no going back, and no undoing the damage, which means we need to be very intentional when using this stable isotope analysis, and find ways to maximize the data we’re able to get from the tooth samples.

Knowing I wanted to look at dietary changes around adolescence, I examine second and third molars (teeth at the back of your mouth), which develop between about 4.5 and 23.5 years of age. I expected to see that males would have this gradual dietary change, as they went from children, to adolescents, to adults. For females, however, I expected a more sudden shift, as everything I was reading suggested they went from being kids to being adults on their wedding day, without a transitional period between the two.

What I found was the complete opposite. Women experienced this gradual and very subtle shift, consuming slightly more proteins as they aged, but no significant changes were noted. For males however, the dietary stable isotope results suggest that around the age of 16, males were suddenly eating less protein.

Trying to understand what was going on, I discovered that 16 is around the age when young men would join the military or start formal apprenticeships. As they moved out of their parent’s homes and into new lodgings (or maybe even new towns) to start these new roles, their diets changed, with less access to protein than they had before. This could be that the military rations included less protein for these low ranked members of the Roman military, or it couldbe that the boys were getting enough money to afford a diet with enough protein, but decided to spend that money on other things, like drinking, games, or brothels, and just ate cheap foods instead. Now that I’ve spent years examining teenagers in the Roman Empire, I’ve learned there is no singular experience of adolescence, but that much like our own modern world, adolescence was a dynamic period of change, that was experienced differently depending on if you were a boy or a girl, if you lived in Gaul (present-day France) or closer to Rome, or a million other factors. But I’ll keep working on it, trying to better understand teenagers who lived over a thousand years ago.

Additional resources

Avery LC, Prowse TL, Findlay S, Chapelain de Sereville-Niel C, Brickley MB. 2023. Pubertal timing as an indicator of early life stress in Roman Italy and Roman Gaul. American Journal of Biological Anthropology 180(3): 548-560. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.24680.

Avery LC, Brickley MB, FIndlay S, Bondioli L, Sperdutti A, Prowse TL. 2023. Eating like adults: An investigation of dietary change in childhood and adolescence at Portus Romae (Italy, 1-4th centuries CE). Bioarchaeology International. 7(2): 130-145. https://doi.org/10.5744/bi.2022.0006.

Avery LC, Brickley MB, Findlay S, Chapelain de Sereville-Niel C, Prowse TL. 2021. Child and adolescent diet in Late Roman Gaul: An investigation of incremental dietary stable isotopes in tooth dentine. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology 31(6): 1226-1236. https://doi.org/10.1002/oa.3033.

Avery LC, Lewis M. 2023. Emerging adolescence: current status and potential advances in bioarchaeology. Bioarchaeology International 7(2): 103-110. https://doi.org/10.5744/bi.2023.0006.

Bareggi A, Pellegrino C, Giuffra, V, Riccomi G. 2022. Puberty in pre-Roman times: A bioarchaeological study of Etruscan-Samnite adolescents from Pontecagnano (southern Italy). International Journal of Osteoarchaeology. https://doi.org/10.1002/oa.3137.

Lewis M. 2022. Exploring adolescence as a key life history stage in bioarchaeology. American Journal of Biological Anthropology. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.24615.

Creighton Avery, PhD, is an Assistant Professor (Teaching Stream) at the University of Toronto, and an osteoarchaeologists with Stantec Consulting Ltd., a cultural resource management firm in Ontario, Canada. Her research takes a biocultural approach, working to understand the lived experiences of children and adolescents in the past.

Her research incorporates osteological and biochemical methods to better understanding the experiences of adolescence in the Roman Empire. This includes understanding when the physical transitions took place (e.g., puberty), and when possible social transitions occurred (e.g., when children started acting like adults). To provide further contextual understanding, she also incorporates archaeological, historical, and literary sources, to help interpret bioarchaeological data.

One thought on “Blog Post #100: Decoding Adolescence in the Human Skeleton with Creighton Avery”