This post is part of a featured blog series on cultural heritage and the legacies of colonialism in the fields of ancient Mediterranean, West Asian, and North African history and archaeology, which is the topic of the fourth season of the Peopling the Past podcast.

Can We Put Looted Antiquities Back into Archaeological Research?

Many archaeologists have faced the same awkward, dinner-party question: “Is there really a difference between archaeology and tomb robbing?”

My controversial answer is: it depends on the context.

Archaeologists usually present their work as legal, methodical, and motivated by research rather than profit. Yet, the damage caused by our fascination with the past means that looting and the illicit trade in cultural heritage remain a heavy topic. Buyers of ancient objects often care more about an item’s value, authenticity, or aesthetic than they do about its journey or the destructive path it took to leave its original context, especially in relation to mortuary contexts.

Efforts to repatriate stolen artefacts have gained momentum in the second half of the 20th century. Italy, in particular, has witnessed substantial repatriation efforts thanks to the work of international collaborations with law enforcement all over the world. Stories regularly surface, for instance, about the Carabinieri (national gendarmerie) uncovering “treasure troves” of looted antiquities tucked away in attics or warehouses around Europe and North America, which are often accompanied by dubious paperwork. These discoveries are then subsequently followed by press conferences celebrating the triumphant return of cultural heritage to its country of origin.

But what happens after the celebrations end?

Can we ethically use these objects in archaeological research without reinforcing the very networks through which they were illegally acquired? If yes, how might this be accomplished?

These are the questions I pose in my dissertation, which is part of a larger project dealing with illegal antiquities in museums and collections – that is, the Symes-Aarhus Project. I joined the project as its PhD student in 2021, after completing a master’s in Ancient, Medieval, and Renaissance Studies at Utrecht University. Having previously worked with material at excavations, for example at Thorikos, I had never had the opportunity to work with archaeological material found in the network of the illegal art market. This was a unique opportunity to further archaeological research and participate in a wider public debate on questions such as, who owns the past?

The Symes–Aarhus Project

In 2014, a warehouse owner in Geneva’s Freeport reported that one of his tenants had abandoned a storage unit. Inside were 45 crates filled with antiquities, including Etruscan sarcophagi, bronze fragments, Roman frescoes, and countless pottery sherds. The tenant in question was Robin Symes, a disgraced art dealer known for trafficking looted objects. Swiss authorities alerted the Carabinieri, and, in 2016, the material was transferred to Rome. Thanks to collaborations between the Carabinieri, the Danish Institute in Rome, and the Carlsberg Glyptotek, a project was launched to study a selection of the material, specifically three of the 45 crates, which contained a total of 32 cardboard boxes filled with South Italian ceramics (Figure 1). In 2018, the Apulian material from the shipment was deposited on long-term loan at Aarhus University, where further research could be carried out. Following the loan of the material, the project, entitled Illicit Antiquities in the Museum, received funding from the Independent Research Fund of Denmark in 2020 to study the fragments in detail and to develop methods for ethically restoring the archaeological value of objects that had lost their original contexts through illegal excavation and trade. This project is led by Vinnie Nørskov, the director of the Antikmuseet at Aarhus University.

The primary goal of this project was to develop novel methods to ethically recontextualise these objects (meaning without supporting the illicit art market), ultimately enabling them to meaningfully contribute to archaeological research without erasing or ignoring their illicit history.

The Method

Objects, whether ancient or modern, exist within many different contexts, and their meaning changes with each one. A vase might serve a ritual function as a grave good, a practical one for daily use, or even a new symbolic role when placed in a modern museum.

Looted antiquities on the art market also have complex lives:

- They were once grave goods, household items or ritual objects, used by people in the past, and sometimes reused later.

- They became commodities dug up by tomb robbers (tombaroli in Italy).

- They were passed through various hands, hidden and sold, and eventually ended up in warehouses like Symes’ Geneva unit.

- Some ultimately enter museum collections or private hands.

To ethically reintegrate the Symes–Aarhus material, I developed the Accumulated Context Method: a research approach that reconstructs an object’s full biography, highlighting each phase of its existence – that is, both its legal and illegal contexts. Moreover, this method emphasizes the interconnectedness of all contexts, which is crucial for research, as each context informs and enhances our understanding of the others. For instance, the findspot context can provide evidence regarding when the material entered the market and may reveal links to specific middlemen or even tomb robbers involved in the looting. Insights drawn from this context help reconstruct the looted landscape, allowing researchers to narrow down sites of interest to recontextualise the material by analysing which sites were targeted and when. Additionally, material remains found by local archaeological authorities that excavated looted tombs, such as sherds from ceramic material left by looters, can potentially be linked to the objects recovered in the warehouse.

Here’s how it works:

- The Findspot Context

We start with the findspot. For this project, this was the warehouse wherein Robin Symes had deposited some of his material (namely 45 crates containing objects such as stone sarcophagi, bronze objects, frescoes, and ceramics), probably due to/during the legal dispute between him and the family of his deceased partner, Christos Michaelides. The objects were stored in 32 boxes which were kept in 3 of the larger crates found in the warehouse, wrapped in bubble wrap and newspapers dated from 1988–1995. Some boxes had Dutch labels, others bore handwritten notes identifying the dealers and middlemen the material had moved through. Most fascinating were the polaroid photographs, each showing a selection of the fragments mid-restoration, providing vital clues for piecing together the over 1,500 sherds (Figure 2). From this material and the accompanying evidence, we reconstructed about 50 vases.

- The Production Context

Next, we examine how, when, and where these vases were made. An analysis of the fabric, vessel shapes, decorative styles, and iconography all pointed toward an early Hellenistic Daunian and Peucetian origin for many of the reconstructed vases, as well as a few Attic and Lucanian vessels from the late Classical period. The rich imagery on some pieces, including depictions of mythological creatures and distinctive clothing styles, offered a window into the cultural world to which they once belonged. - The Looted Landscape Context

Using the clues from the Geneva storage locker (newspaper dates, box markings), aerial photography, excavation reports, and interviews with local archaeologists, we could narrow down where the material likely came from: the Foggia–Canosa area, a historically rich Daunian region heavily affected by looting in the 1970s and 1980s. I was even able to visit the local archaeological superintendency of Foggia to analyse material found during their excavations in tombs that were looted, and to make any possible connections. - The Cultural Landscape Context

Finally, we explore the role that these vases played in ancient society, especially in relation to funerary practices. The size and design of several large volute kraters suggest that they once belonged to chamber tombs, like those found in Arpi, a major Daunian settlement thriving during the Early Hellenistic period.

Through this layered approach, we can weave a narrative that acknowledges both the objects’ ancient histories and their modern journeys without sanitising the uncomfortable truths of their illicit past.

Moving Forward

For my PhD, I applied the Accumulated Context Method to two monumental volute kraters reconstructed from material found in the Robin Symes warehouse. Through careful analysis, we concluded they likely originated from Arpi’s Early Hellenistic chamber tombs. We arrived at this conclusion by comparing the size and shape of these two vases with others found in the same area, and observing similarities in their decorations within the local cultural landscape, such as evidence of increased contact with Macedonian kings. These vases also appear to be contemporary with a number of chamber tombs in the region (which were the only graves large enough to house monumental volute kraters). We know the time period of the tombs from which the volute kraters were looted and when these tombs were looted thanks to rescue excavations by the local archaeological services (Soprintendenza Archeologia, Belle Arti e Paesaggio per le Province di Barletta-Andria-Trani e Foggia). Based on the information from those excavations, it was possible to compare material found and some of these tombs, and to tentatively connect them to the material found there (ceramic sherds).[1]

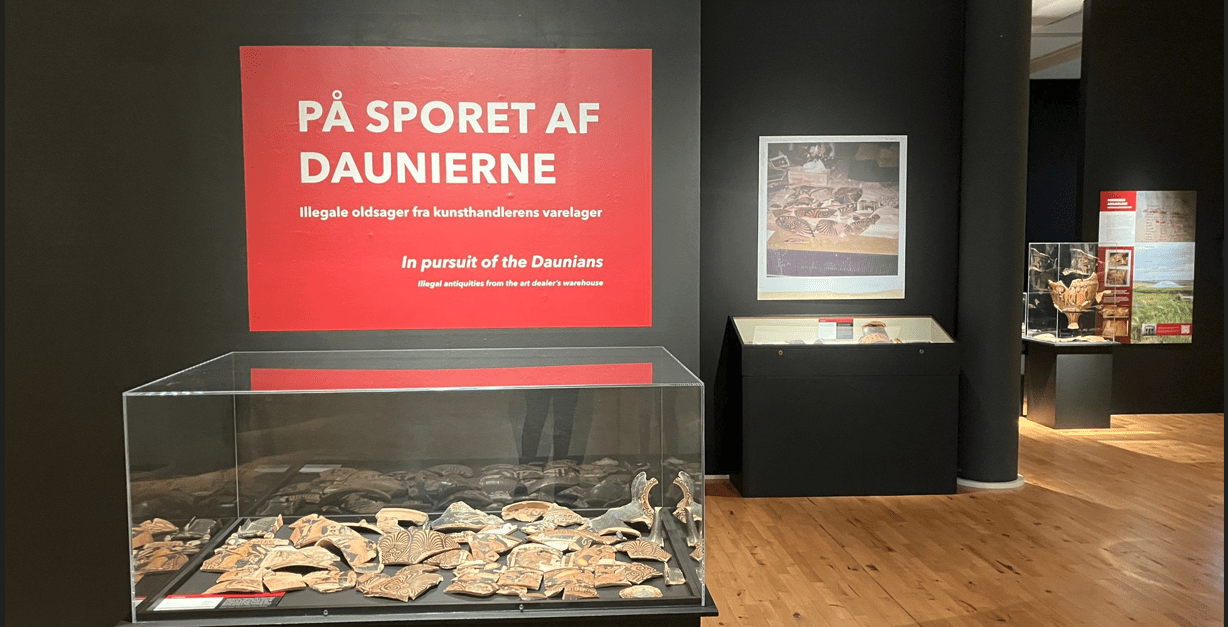

(Photo by author, Illicit Antiquities in the Museum)

By treating looted objects not as shameful remnants to be hidden away, but as complex historical witnesses, we can reintroduce them into archaeological scholarship, not forgetting the circumstances of their displacement. Hopefully, this work will be a first step toward dealing with the question of what we can do with archaeological material found to be acquired illegally, after it has been repatriated.

On April 30, 2025, an exhibition called In Pursuit of the Daunians highlighting this project opened at the Museum of Ancient Art and Archaeology (Antikmuseet) in Aarhus, featuring reconstructions of the vases, which were placed next to the boxes, polaroids, and newspapers from the Genevan warehouse, along with information on Arpi from archaeological digs, a movie by the artist Maeve Brennan, and more. I highly recommend visiting the exhibit, if one should find themselves in the area between now and the end of 2025, as it offers us an opportunity to re-conceive how we might display and interact with objects that were illicitly acquired.

[1] We have not yet been able to confirm this as they do not connect directly, but this might be a possibility in the future using archaeometric methods.

Marie Hélène van de Ven is a classical archaeologist specialising in the study and recontextualisation of looted archaeological objects. As a researcher on the project Illicit Antiquities in the Museum at Antikmuseet, Aarhus University, she investigates the many different contexts to which looted artefacts belong, focusing on their ancient and modern histories and the ethical implications of their display and study. Her current work centres on a collection of Apulian red-figure pottery fragments, originally seized from the Geneva warehouse of art dealer Robin Symes and repatriated to Italy before being deposited in Aarhus. By reconstructing these fragmented vases and tracing their object itineraries, she aims to recontextualise them within their original archaeological and cultural settings, thereby shedding light on the broader networks of looting and trafficking that have shaped their journeys.

Like our content? Consider donating to Peopling the Past. 100% of all proceeds support honoraria to pay the graduate students and contingent scholars who contribute to the project.

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is appreciated. Please note that we cannot provide tax receipts, as we are not a registered charity.

Your contribution is appreciated. Please note that we cannot provide tax receipts, as we are not a registered charity.

Your contribution is appreciated. Please note that we cannot provide tax receipts, as we are not a registered charity.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearly