Content Warning: This blog contains images of human remains. Please see here for Peopling the Past’s statement on the discussion and display of human remains.

The Roman army has been the subject of relentless fascination for centuries now. Rarely out of fashion, studies on the imperial army’s effectiveness at war, its organizational structure, the life of the legionary soldier, and other related topics have proliferated, for an audience ever eager to learn more about what was arguably the ancient world’s most complex, successful military. Such attraction is not without reason: the imperial army was recognizably the single largest institution in Roman society, one whose existence over hundreds of years represented Rome’s most critical, sustained investment of human and economic capital. As such, we are obliged both to acknowledge and consider carefully the deep, perpetual impact that Rome’s military had directly and/or indirectly upon Rome’s citizens and subject peoples alike.

Since the 1990s, two related topics have received significant, much-needed attention: Rome’s auxiliary forces – units of non-citizen soldiers stationed across the empire in support of the legions – and its military communities, particularly those permanently garrisoned upon Rome’s frontiers. The personnel and bases of the former have recently been the subject of excellent synthetic and specialized studies (e.g., Haynes 2013, Van der Veen 2020), as has the investigation of the latter, their internal organization, and the character of their diverse populations (e.g., Driel-Murray 1998; Allason-Jones 1999; Allison 2013; Meyer 2020; Greene 2015, 2016, 2020). What has emerged from this new research is a deepening recognition of the integral, essential role that non-Romans and non-soldiers played in military activity and daily life, as well as a broadening acknowledgement of group and individual identity within what is still often viewed as a monolithic, heavily standarized, and strictly gendered institution.

Roman Gordion: An Auxiliary Roadside Base

In comparison to the Roman West, comparatively little is known so far about military communities in the eastern Mediterranean. For instance, we know little about the vital supply network constructed to sustain units permanently stationed on the upper Euphrates, a force of roughly 20,000 soldiers needing unceasing, perennial support. When Rome was occasionally at war in the East, such demands were greatly amplified; Trajan’s invasion of Parthia between 114–17 CE, with an estimated mobilization of ca. 160,000 soldiers, represents one such occasion (Bennett 2000). To carry out the onerous task of provisioning, Rome placed small detachments of auxiliaries at strategic roadside locations across central Anatolia, at small bases (stationes) designed to maintain local security, ensure communications, and gather essential supplies (meat, wool, grain, fodder, etc.) for the distant garrisons and/or expeditionary forces. The work was indispensable and unglamorous, yet not without reward: for completing 25 years of service these non-Roman servicemen would receive citizenship for themselves and their descendants. Significantly, surviving bronze plaques (diplomata) officially commemorating such grants include on occasion the names of wives and children, providing critical evidence for family units among auxiliaries in service (Greene 2015).

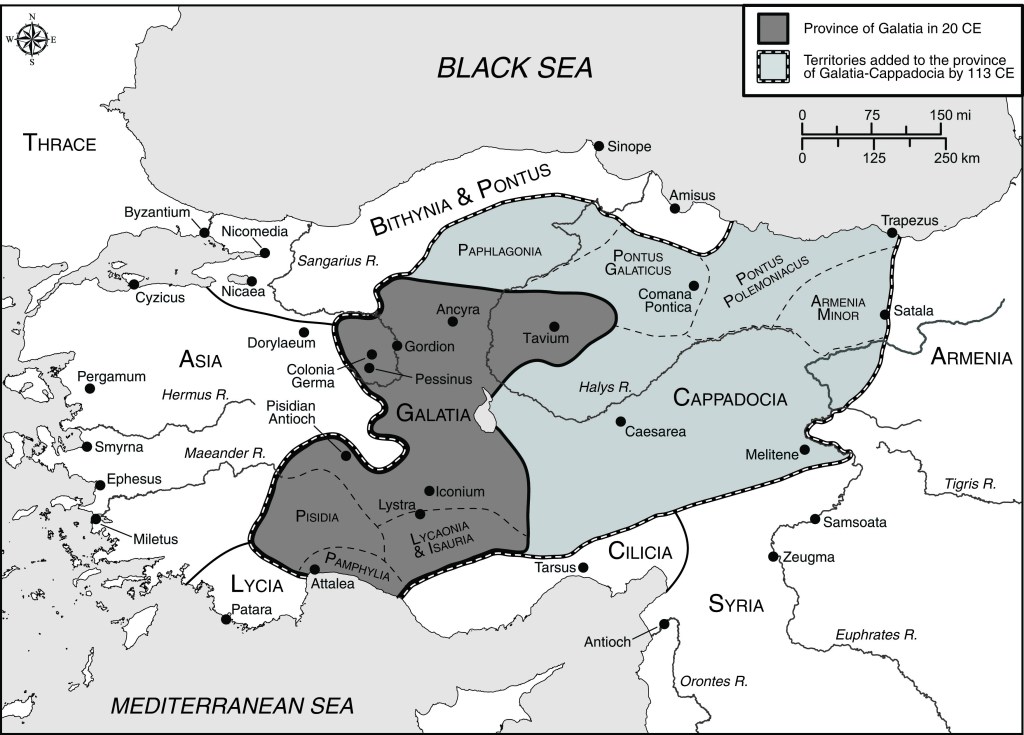

My work at ancient Gordion, a massive Iron Age site in central Turkey that once served as the capital of the Phrygian kingdom, represents one of the first attempts to investigate in depth an auxiliary community in the Roman East. Excavation and survey carried out under the auspices of the University of Pennsylvania Museum since 1950 have identified remains of the first statio in the province of Galatia (central Turkey), permitting a rare opportunity to study the function and character of a military community far from Rome’s frontier (Fig. 1). Dating from the mid-1st to early 2nd century CE (with a later reoccupation in the late 3rd and 4th centuries), the base and its multiple necropoleis have yielded invaluable new data about life among the auxiliaries stationed in the provincial hinterlands (Fig. 2). For example, faunal and archaeobotanical analyses have indicated strong connections with local cereal farmers and pastoralists, revealing a nexus of long-term collaboration between the military and Galatia’s indigenous population (Çakırlar, Marston 2019). In addition, examination of the Roman necropoleis at Gordion has verified the presence of men, women and children at the base, many of whom bore on their feet hobnailed footgear, some of which perhaps represent military sandals known as caligae (Goldman 2010).

Peopling Roman Gordion: Pannonians Abroad?

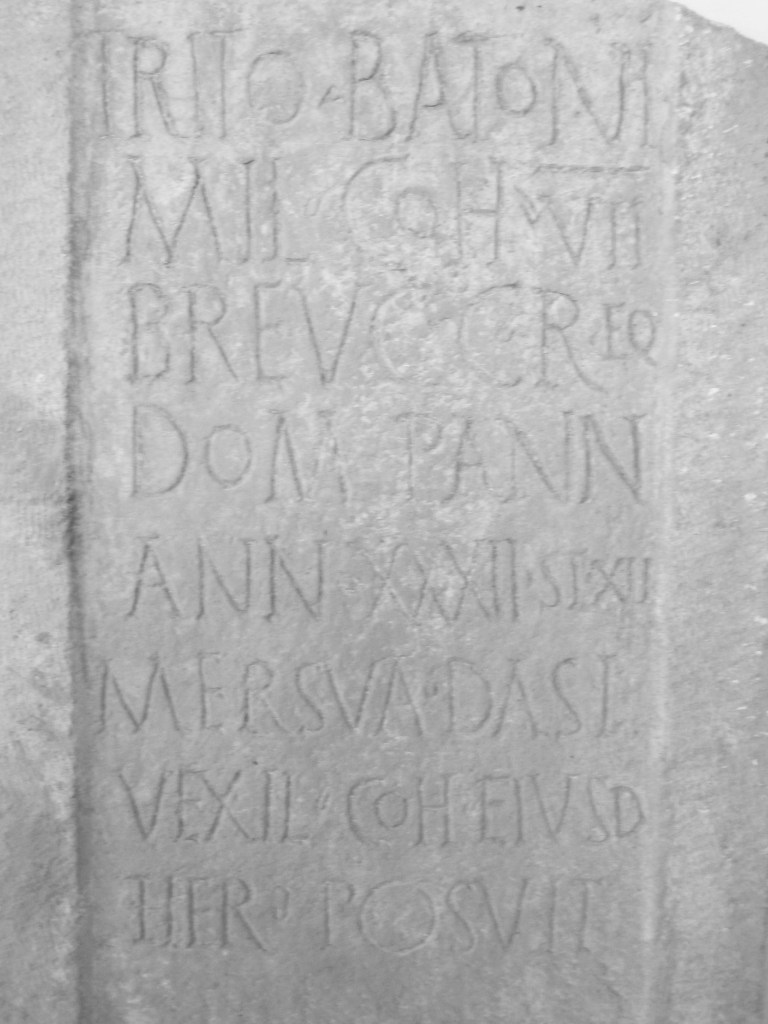

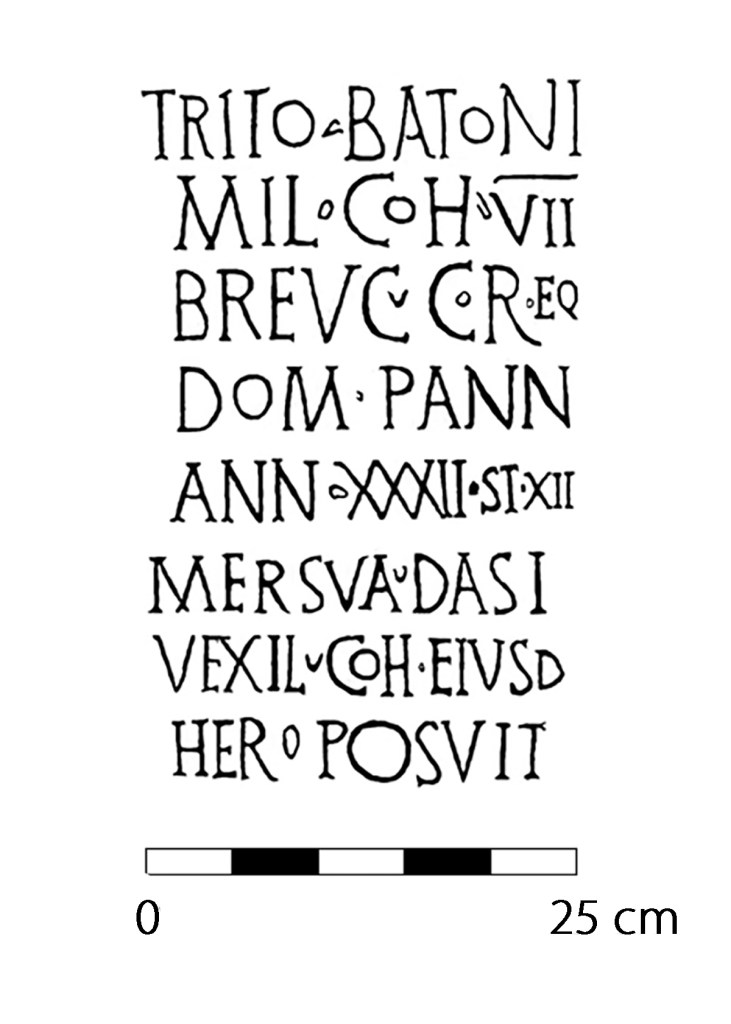

Unquestionably our most difficult task has been to identify the origin of Gordion’s military residents. That many were non-locals is certain, as the base represents a fresh foundation following a total abandonment of Gordion’s Citadel Mound for at least a century. An important clue came to light in a nearby field in 1996: a funerary stele with an 8-line Latin inscription (Fig. 3a/b) that named a specific military unit – the cohors VII Breucorum – and included the Pannonian origin (origo) of the deceased. Study of the unit, its history and contemporary military diplomas indicate that the auxiliary, Tritus, likely arrived at Gordion in or around 113 CE, when Trajan and his army wintered in Galatia just prior to his four-year invasion of Parthia (Goldman 2010). Excavation of the base has revealed a major refurbishment effort (Phase 2C:3) convincingly linked to this deployment, a significant upgrade in size and facilities necessitated by the arrival of a new, larger garrison.

Might this influx of expeditionary soldiers consist of Pannonians abroad? It is an attractive hypothesis, but difficult to substantiate, since only relatively small portions of the base have been excavated to date. Epigraphic evidence is unhelpful; only four Roman inscriptions (all in Latin) have been found at Gordion, and the other three pre- or post-date this deployment (Darbyshire, Harl, Goldman 2009). Ceramic forms and decoration recovered from secure 2C:3 deposits display tantalizing hints, such as stylized stamps of plant leaves of the type found on dishes of pannonische Glanztonware (PGW), to indicate that imported or imitated popular Pannonian pottery circulated at the base.

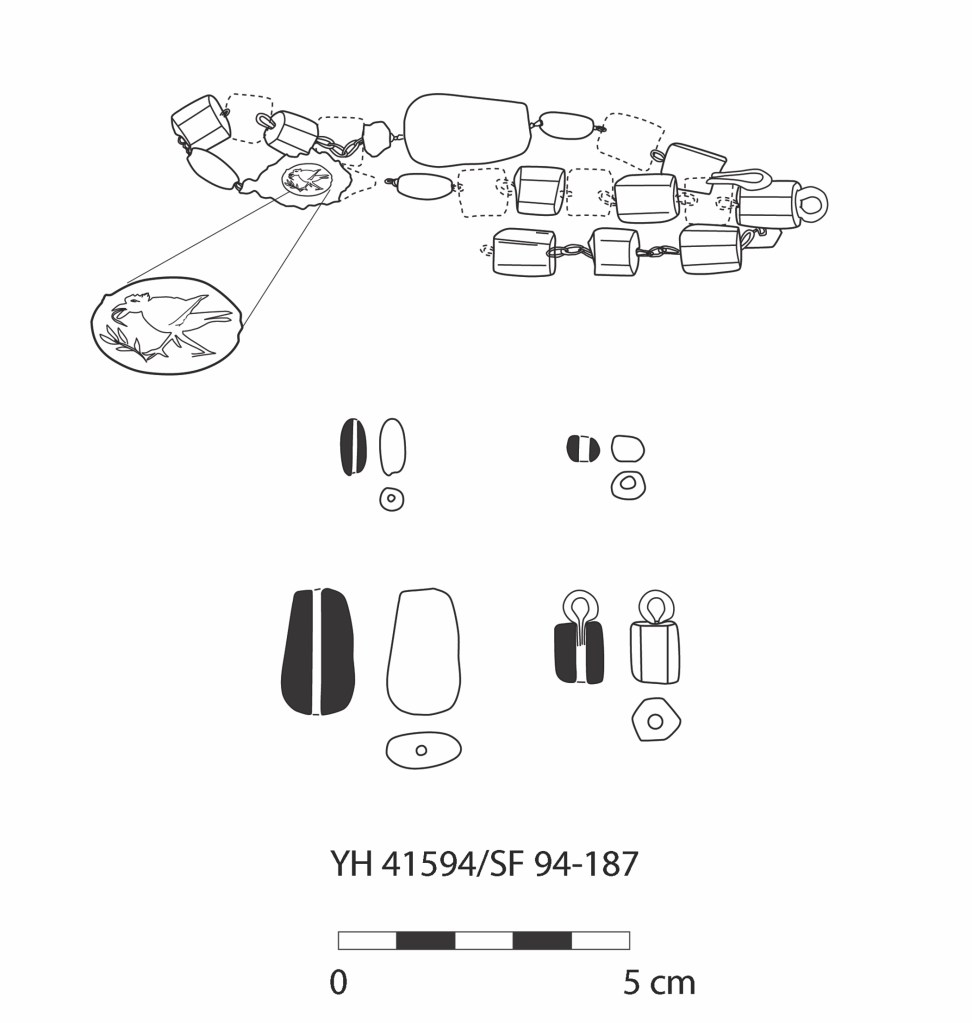

The most fascinating potential evidence comes from a grave excavated in 1993–94 by the author in the South Lower Town Cemetery. The simple pit burial (LTG-12) contained the body of a young woman (15–18 years old) found laid upon her back, with dark purple staining on her skull and upper vertebrae (Fig. 4). Placed by her left ankle was a long strand of glass and semi-precious beads, including a large tab of amber (Figs 5–6). A lengthy search for comparanda revealed no published equivalents in Anatolia. Rather, similar ornamental jewelry placed in an identical fashion is documented in cemeteries in southeastern Hungary, with excellent parallels among 16 graves of a Sarmatian women’s cemetery at Makó-Igási Járandó near Csongrád (Balogh 2015). In addition, the staining on the skull – also with no parallels at Gordion or in Anatolia – suggests that the deceased was interred with some type of headband or headgear. Is this possible evidence of the ethnic origin of the deceased? Somewhat exceptionally, women living in Pannonia and neighboring Noricum were well known for their elaborate headgear (Garbsch 1985), a fact that could account for the presence of a headband or cap placed upon the deceased’s head. Could this burial contain evidence of a young Pannonian or perhaps Sarmatian woman who accompanied an expeditionary soldier to Galatia? Might she have been a family member, or perhaps an enslaved person? Disappointingly, the skeleton has not yet received archaeogenetic testing, so that we cannot confirm such a hypothesis via DNA evidence. At this time, we can thus only speculate about the ethnic origin of the deceased, in what is a currently unique grave at Gordion and, to the author’s knowledge, in Anatolia in general.

Conclusions

The movement and garrisoning of the Roman army was a complex undertaking; careful logistical planning and stationing of forces were necessary to ensure both short- and long-term stability. The evidence from Gordion helps to support what we have already learned about auxiliary forces in the Roman West: their small bases were peopled not merely with servicemen, but rather should be understood as integrated communities consisting (at least in part) of formal or informal family units. In a rural, roadside garrison like Gordion, permitting family units makes intuitive sense, an act that would render more bearable the long period of service and the likely dull, exacting life of an auxiliary soldier. For auxiliaries on expedition, evidence from Gordion’s cemeteries might also suggest that in some cases it was permissible for officers or soldiers to be accompanied abroad, if that is indeed what our exceptional burial signifies. In any case, our new evidence from Gordion acts to reinforce our growing understanding that the auxiliary bases of Rome were hardly a world of men only, but rather were peopled across the empire by multi-gendered, multi-generational populations.

Additional Resources

Allason-Jones, L. 1999. “Women and the Roman Army in Britain.” In The Roman Army as a Community, eds. A. Goldsworthy and I. Haynes, pp. 41-51. Portsmouth RI: Journal of Roman Archaeology.

Allison, P. M. 2013. People and Spaces in Roman Military Bases. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Balogh, C. 2015. Szarmata temető Makó-Igási járandóban/Sarmatian cemetery at Makó-Igási járandó (County Csongrád, Hungary). In A népvándorláskor fiatal kutatóinak 24th konferenciája Esztergom, 2014/Conference of Young Scholars on the Migration Period, Esztergom, 2014. Vol. 1 (Hadak Útján 24), ed. A. Türk, C. Balogh, and B. Major, pp. 257–320. Budapest: Archaeolingua.

Bennett, J. 2000. Trajan: Optimus Princeps. London: Routledge.

Çakırlar, C. and J.M. Marston. 2019. Rural Agricultural Economies and Military Provisioning at Roman Gordion (Central Turkey). Environmental Archaeology 24.1:91-105.

Darbyshire, G., K. Harl, and A. Goldman. 2009. ‘To the Victory of Caracalla’: New Roman Altars at Gordion. Expedition 51(2):31–38.

Driel-Murray, C. van. 1998. A question of gender in a military context. Helinium 34 [1994]: 342- 62.

Garbsch, J. 1985. Die norisch-pannonische Tracht. Aufstieg und Niedergang der römische Welt 2.12.3:546–77.

Goldman, A. L. 2007. The Roman-period Cemeteries at Gordion in Galatia. Journal of Roman Archaeology 20:299–320.

—–. 2010. A Pannonian auxiliary’s epitaph from Roman Gordion. Anatolian Studies 60:129–46.

—–. 2017. New Evidence for Non-Elite Burials in Central Turkey. In Life and Death in Asia Minor in Hellenistic, Roman and Byzantine Times. Studies in Archaeology and Bioarchaeology, ed. J. R. Brandt, E. Hagelberg, G. Bjørnstad and S. Ahrens, pp. 149–75. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

Greene, E. M. 2015. Conubium cum uxoribus: Wives and Children in the Roman Military Diplomas. Journal of Roman Archaeology 28:125–59.

—–. 2016. “Identities and Social Roles of Women in Military Communities of the Roman West.” In Women in Antiquity: Real Women across the Ancient World, eds. S. Budin and J. Turfa, pp. 942-953. London: Routledge.

—–. 2020. Roman Military Communities and the Families of Auxiliary Soldiers. In New Approaches to Greek and Roman Warfare, ed. L. Brice, pp. 149–59. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Haynes, I. 2013. Blood of the Provinces. The Roman Auxilia and the Making of Provincial Society from Augustus to the Severans. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Meyer, A. 2020. Approaching “Ethnic” Communities in the Roman Auxilia. In New Approaches to Greek and Roman Warfare, ed. L. Brice, pp. 161–72. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Van der Veen, V. 2020. Roman military equipment and horse gear from the Hunerberg at Nijmegen. Finds from the Augustan military base and Flavio-Trajanic castra and canabae legionis(Auxiliaria 18). Nijmegen: Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen.

Andrew L Goldman is a Professor in the Department of History at Gonzaga University in Spokane, WA, where he has worked since 2002. He received his doctorate in Classical Archaeology from the University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill. He has been a team member of numerous archaeological field projects in Turkey, Sicily, Sardinia, and Cyprus. While he concentrates primarily upon the investigation of ancient Roman material culture, his academic interests vary widely, from the study of small, mundane objects like carved gemstones and what they can tell us about Roman-period culture, to addressing broader questions which span the topics of war and death in the Roman Republic and Empire, through the examination of battle sites, military camps and cemeteries. Between 2004–06, he directed the excavation of the Roman auxiliary base at Gordion in central Turkey; from 2013–18 he was the field director of the Sinop Regional Archaeological Project (SRAP); and he is currently a member of the Aegates Islands Maritime Survey team in western Sicily, where he is analyzing the Roman Republican military finds from the Battle of the Aegates Islands (241 BCE). For the 2025–26 academic year, he is serving as the Professor-in-Charge at the Intercollegiate Center for Classical Studies (ICCS) in Rome, and frankly loving it.

Like our content? Consider donating to Peopling the Past. 100% of all proceeds support honoraria to pay the graduate students and contingent scholars who contribute to the project.

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is appreciated. Please note that we cannot provide tax receipts, as we are not a registered charity.

Your contribution is appreciated. Please note that we cannot provide tax receipts, as we are not a registered charity.

Your contribution is appreciated. Please note that we cannot provide tax receipts, as we are not a registered charity.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearly

One thought on “Blog #113: Pannonians Abroad? New Evidence from a Roman Auxiliary Base in Central Turkey with Andrew L. Goldman”