For Halloween month, our blog posts focus on the theme “Cursing in the Ancient World”. Our authors explore the notorious practices of curse tablets and other magical spells, and reflect on the deeper human tendencies that underpin these acts.

What topic do you research?

I examine curse tablets to understand embodiment, intersecting identities, power structures, violence, and resistance in the Roman empire. Curse tablets were written by and directed against a wide range of people—from enslaved women to emperors—related to institutions crucial to our understanding of ancient society, such as the arena, enslavement, commerce, court proceedings, baths, and marriage. They were deposited in intricate rituals, involving dolls with pins in them or dismembered chickens or even the human hair of their victim.

While lots of incredible work has been done on curse tablets—which are incredibly difficult textual objects to transcribe, let alone interpret, as I will discuss below—most current scholars have denied, underplayed, or sidestepped how violent they were towards their victims. What happens if we don’t shy away from curse tablets’ specific corporeal language and deliberate ritual treatment that, in most ancient people’s worldview, harmed, maimed, and even killed people? How did curse tablets impact people’s bodies and by what mechanisms did they do so? What is the relationship between language, ritual practice, and violence?

Taking curse tablets seriously as acts of violence also allows us to situate curse tablets with more nuance and depth in the Roman empire. What were the social relationships like between people involved with curse tablets, whether as victims, authors, scribes, attending priests? How did curse tablets reinforce, subvert, or circumvent power dynamics around gender, status, race, wealth, ability in social, political, legal, and entertainment contexts? Finally, how do we position curse tablets within our understanding of the Roman empire? Were they fringe practices, or, though taboo, were they embedded in and representative of other aspects of Roman culture?

The core of my work seeks to untangle the relationship between language, ritual, violence, including what types of and justifications for harm are considered “violent”– and which people are granted enough humanity to be called “victims.” I cannot pretend to care about the ways language justifies and enacts violence if I do not take this opportunity to voice how this is happening today. Israeli attacks on the Palestinian people are currently being framed as a “reasonable response” to Hamas’s “unprovoked” attacks. This framing ignores the 75 year occupation of Palestine by Israeli state and ongoing genocide in Palestine and Gaza– the largest open-air prison in the world where all access to food, water, and electricity, has been cut off. Justifying Israel’s escalation of violence is not the answer, nor are Hamas’s attacks; all violence is abhorrent, and we should seek peaceful solutions.

What sources or data do you use?

In my dissertation, I examine curse tablets from the 1st-5th centuries CE throughout the Roman empire through personal autopsy and Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI).

Of the roughly 600-750 curse tablets from the Roman Empire, I am examining approximately a hundred and fifty in-depth. I chose tablets that discuss body parts, ability phrases, or the materiality of lead explicitly. I selected some individual tablets and a few groups of curse tablets from well-excavated contexts so we have more information about their accompanying rituals and can say more about them as groups. These include tablets from wells in the Athenian Agora, the Temple of Sulis Minerva in Bath, the Temple of Magna Mater and Isis at Mainz, and the Sanctuary of Demeter and Kore at Acrocorinth.

In addition, I study a few single tablets, such as a 1st-century CE tablet found in a cinerary urn in Nomentum, Italy against a man of unknown status on one side and an enslaved woman on the other, a tablet from Carthage that has blanks where the target’s name would be, and a 3rd-century CE curse from Hermopolis Magna, Egypt that features the longest coercive erotic spell between two women. The curses in my study are representative of curse tablets as a whole because they appear in both Latin and Greek, were directed towards many different types of people under every common social circumstance, and were from so many different archaeological and geographic contexts.

I’ve been lucky to examine many of the tablets I’m studying in person, which has helped me learn a lot more about how people handled them and how they impacted people’s bodies. For example, there can be tiny stylus marks where writers began writing one letter but decided to write a different letter instead, telling us where they hesitated, either because of strong emotions or spelling confusion. On one tablet, someone inscribed a magical invocation twice, on top of itself, as if it were bolded. Did that give that word more power?

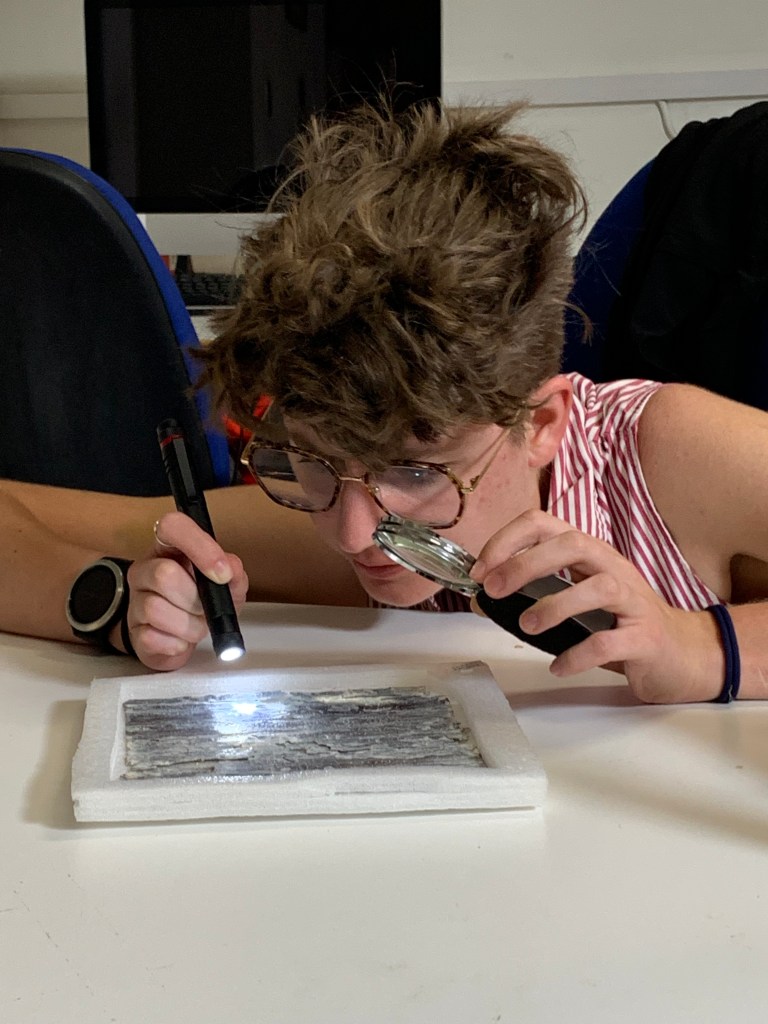

These and other aspects of curse tablets are very difficult, if not impossible, to see with the naked eye or even magnifying lenses. Curse tablets are small (normally under 20 cm long) and lead has an uneven and difficult surface. This past summer, I was able to use the Dodec RTI dome to take much clearer image sets of the tablets. The RTI dome has already allowed me to much more easily transcribe a tablet from Corinth, to see some letters that were not in earlier publications, and replicate the in-person viewing experience on a screen. I also can examine the order each stroke was written on every letter, something that takes too much time to complete in person. While order letter strokes were written may seem minute, these gestures are also a better way to attribute tablets to certain writers, which has implications for agency and the social role of curse tablets.

Personal autopsy with curse tablets is not without its occupational hazards. Two days after examining a tablet in Florence in which a woman named Sophia– my name– sought to “burn, set on fire, | inflame the soul, the heart, the liver, the spirit of Gorgonia”, I also developed a fever!

How does your research shed light on real people in the past?

Often, curse tablets are the only record we have of these specific people in the past, like Gemella, who was thought to have stolen bracelets; Eutyches, the grammarian from Smyrna; and Rufa, a woman enslaved to the city of Rome. People involved in curse tablets have a wide range of various intersecting identities along the lines of gender, status, race and ethnicity, age, occupation, and ability.

This keeps me up at night. What if the only record of me, two thousand years from now, was something horrific someone wrote about me? Not just wrote about me, but wrote with the intention of harming or killing me in graphic ways? I don’t want to excuse the curse tablet writers’ intended harm or not acknowledge the victims’ humanity; and in some cases, the victims of violence in one case were perpetrators in another.

My research involves a degree of critical fabulation, following Saidiya Hartman’s “Venus in Two Acts.” Since curse tablets only capture a single moment in time, we can imagine myriad narratives from the same tablet, and this I hope to do in the third chapter of my dissertation.

Some curse tablets tell stories of hope. One tablet seeks to ensure that the manumission ceremony of Eros of Rhodes would be successful. We do not know whether his enslaver or other witnesses did speak out and thus render obsolete the Eros’s manumission ceremony, or if they did, if they experienced any psychosomatic symptoms like the ethnographically-attested “curse death.” We do know that Eros- or someone who cared about him- had the money, literacy, or other knowledge to try to protect him.

Additional Resources

Blänsdorf, Jürgen, Pierre-Yves Lambert, and Marion Witteyer, 2012. Forschung zur Lotharpassage: Die Defixionum tabellae des Mainzer Isis-und Mater Magna-Heiligtums. Generaldirektion Kulturelles Erbe (GDKE). Direktion Landesarchäologie.

Jordan, David R., 2022. “Curse Tablets of the Roman Period from the Athenian Agora.” Hesperia: the Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 91(1): 133-210.

Gager, John G., 1992. Curse Tablets and Binding Spells from the Ancient World. Oxford.

Lamont, Jessica, 2023. In Blood and Ashes: Curse Tablets and Binding Spells in Ancient Greece. Oxford.

McKie, Stuart, 2022. Living and Cursing in the Roman West: Curse Tablets and Society. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Reiss, Werner. 2013. Performing Interpersonal Violence: Court, Curse, and Comedy in Fourth-Century BCE Athens. De Gruyter.

Stroud, Ronald S, 2013. “The Sanctuary of Demeter and Kore: The Inscriptions.” Corinth 18, no. 6: iii–184.

Tomlin, Roger, 1988. Tabellae Sulis: Roman inscribed tablets of tin and lead from the sacred spring at Bath, Oxford.

Torallas Tovar, Sofia, and Raquel Martin Hernandez, 2022. Materiality of Greek and Roman Curse Tablets. Oriental Institute of Chicago.

Sophia Taborski is a PhD candidate in classical archaeology. She received her B. Phil. from the University of Pittsburgh in Classics and History and has taught English, Latin, and history in primary and secondary education. In her dissertation, titled “Inscribing Violence: Curse Tablets in the Roman Empire” she examines the texts, contexts, orthography, and materiality of curse tablets to explore violence, embodiment, power dynamics, and intersectional identities and experiences such as disability, enslavement, race, gender, and sexuality. She has taken RTI (Reflectance Transformation Imaging) image sets of curse tablets in the Medici Library in Florence, the Diocletian Baths Museum in Rome, the Roman Bath Museum in Bath, and in the Stoa of Attalos in Athens and the National Archaeological Museum of Corinth as an Associate Member of the American School for Classical Studies. She has excavated in Argilos, Greece, and at St. James AME Zion Church, Ithaca. Other interests include religion, medicine, cognitive approaches, pedagogy, and domestic arch