Peopling the Past brings you an ongoing blog series, “Unknown Peoples”, featuring researchers who investigate understudied and/or marginalized peoples in the past.

Italian history has long been dominated by the sprawling shadow of Rome, a narrative anchored in conquest and imperial expansion. In many respects, such a perspective is essential to understanding the social, cultural, and political developments of the Italian peninsula. Yet, beneath this narrative lies a tapestry of ancient Italian cultures that thrived before and during Rome’s ascension.

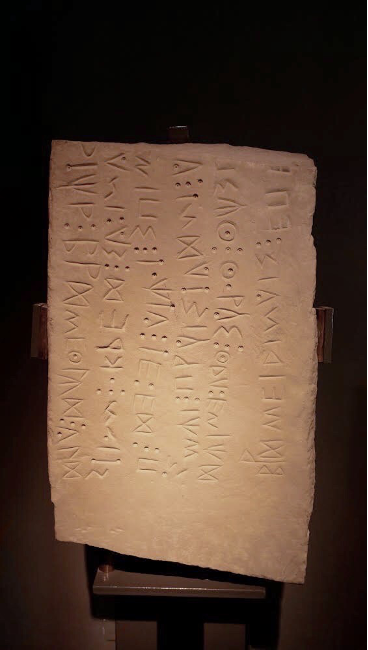

As M. Pallottino already noted in 1984, even ancient Greek and Roman authors had a clear sense of the fact that Italy was a mosaic of diverse peoples before the juridical, cultural, linguistic, and political unification realized by Rome. However, as indigenous historical accounts have not come down to us, we have both to navigate through the labyrinth of biases of Greek and Roman historiography and rely on archaeology and epigraphy to really understand who the indigenous people of Italy were and how they interacted with the Roman expansion in Italy. My own research aims to tackle this issue by studying indigenous Italic languages and writing practices from the angle of social history. Looking at Roman and non-Roman epigraphic materials, I hope to show how writing and linguistic choices can shed light on indigenous agency in and resilience to “Romanization” dynamics.

The Peoples of Ancient Italy

Before the rise of the Roman Empire, the Italian Peninsula was home to various ethnic groups collectively referred to as the Italic or pre-Roman peoples. Umbrians, Bruttii, Lucanians, Samnites, Volscians, Latins, Etruscans – these are but a glimpse into the rich diversity that characterized the Italian peninsula between the 7th and the 1st century BCE. During that time, Italy was a realm of permeable boundaries and high levels of mobility. This makes defining Italic peoples’ identities a complex process that has to take into account factors such as ethnic origins as well as civic affiliations, social status, age, and gender. Even defining and locating Italic communities in space presents a unique challenge, as the self-perceptions of Italic peoples often diverged from Greek or Roman categorizations.

For instance, while the Greeks referred to the Etruscans as Tyrrhenoi and the Romans as Etrusci, literary and Etruscan epigraphic sources reveal that they referred to themselves with the ethnic Rasenna. Archaeology provides partial clarity to this intricate picture, enabling the identification of groups sharing funerary habits, religious rites, and material culture. Epigraphic evidence, on the other hand, allows us to group together people writing in the same languages. What emerges then is a multi-layered and intricate picture in which different cultural, linguistic, and archaeological cultures exist in the fluid and interconnected Mediterranean landscape. Some of the Italic communities, like the Etruscans, developed early urban cultures, while others, like the Samnites, are attested as nomadic, tribal communities. Some communities created and utilized unique scripts as a form of cultural expression and identity. Others adapted foreign alphabets to suit their language or simply did not make extensive use of writing. Although the complexity of this scenario may look challenging and daunting, it actually represents an incredible opportunity to develop new perspectives on cultural interactions and analyze the impact of empire and state formations on diversely organized societies.

Rediscovering and Reclaiming Italic Indigenous People Agency

The absence of native voices has often consigned pre-Roman Italy to a state of inertia. For a long time, the historical and archaeological investigations sought confirmations of the information passed down by Latin and Greek sources, leading to circular reasonings and confirmation biases. Academic research, still influenced by Western-centric and colonial approaches, tended to evaluate Italic communities through a Greco-Roman lens, portraying them as unchanging and uniform entities. In response to these approaches, recent scholarship has endeavored to cultivate a more balanced viewpoint by exploring the interactions between Romans and non-Romans more in-depth.

Drawing inspiration from this ongoing debate, I utilize epigraphic and linguistic evidence not only to unveil a more nuanced depiction of Italic responses to colonization but also to reestablish agency among Italy’s indigenous peoples, transcending rigid portrayals. The ancient Italian world had the capacity to generate innovation independent of Rome’s influence, but this aspect is still underexplored and undervalued. Evidence substantiating this stance surfaced from my study on writing practices in the context of craft production. Analyzing the evolution of writing technologies between the 7th and 2nd century BCE, it is possible to notice how the beginning of mass-produced, inscribed objects was not solely owed to Rome.

It is generally believed that Rome’s new slave economy and inclination to technological advancement impacted Italian structures of production, leading them to evolve and enter new economic networks. Contrarily, my research work discloses a chronology of economic shifts antecedent to Rome’s ascendancy, notably emanating from regions in which Italic people had yet to be assimilated into the Roman sphere of influence. This empirical discovery serves to reinstate the agency of the Italic peoples, thereby attesting to their capacity for pioneering technological advancements and exerting influence over broader economic trajectories independent of Roman patronage.

Conclusions

In conclusion, delving into the diverse cultures of ancient Italy can provide a critical reassessment of historical narratives. It challenges us to break free from preconceptions and venture beyond traditional perspectives on societal development. This approach leads us to unveil entirely different yet interconnected scenarios, revealing a tightly woven fabric of communities endowed with their own agency, capable of innovation independently of Rome’s influence. This is exactly what my research aims to do through the analysis of epigraphic evidence: acknowledging the peoples of ancient Italy as integral components of the history of the peninsula rather than being seen merely as Rome’s adversaries. Their identities remained in a constant state of flux, responding dynamically to the complex interactions of their time. Yet, only by engaging with this complex scenario can we gain a deeper understanding of the rich mosaic that was ancient Italy, transcending the boundaries of the Roman gaze.

Additional Resources

Aberson, M., Biella, M. C., Di Fazio, M., Wullschleger, M. (Ed.). (2020). “Nos sumus Romani qui fuimus ante …”: memory of ancient Italy. Peter Lang.

Bradley, G. J., Riva, C., & Isayev, E. (2007). Ancient Italy: regions without boundaries. University of Exeter Press.

Bradley, G., & Farney, G. D. (Eds.). (2018). The peoples of ancient Italy. De Gruyter.

Clackson, J. (2020). Migration, mobility and language contact in and around the ancient Mediterranean. Cambridge University Press.

Isayev, E. (2017). Migration, mobility and place in ancient Italy. Cambridge University Press.

Pallottino, M. (1984). Storia della prima Italia. Rusconi.

Terrenato, N. (2019). The early Roman expansion into Italy: elite negotiation and family agendas. Cambridge University Press.

Wallace-Hadrill, A. (2008). Rome’s cultural revolution. Cambridge University Press.

Claudia Paparella is a PhD student at the University of Toronto and a member of the Mediterranean Archaeology Collaborative Specialization Program. Her research questions widely engage with the entanglement between language, writing, and identity construction. In her PhD project titled “Indigenous Languages and Identities in the Making of Roman Italy,” she uses epigraphic evidence to trace the social history of indigenous Italian languages and their entanglement with the Roman imperial expansion in Italy (7th-1st century BCE). Broadly speaking, she has been studying modifications in writing practices in ancient Italy to explore a diverse array of themes, including the perception of environmental phenomena and the development of economic trends and new technologies of production. An ongoing archaeological formation complements her interest in ancient history, as she has been involved in international archaeological excavations such as the Falerii Novi Project.