One of Peopling the Past’s goals is to amplify the work of young and/or under-represented scholars and the amazing research that they are doing to add new perspectives to the fields of ancient history and archaeology (broadly construed). We will thus feature several blog posts throughout the year interviewing graduate students on their research topics, focusing on how they shed light on real people in the past.

Peopling the Past brings you our Halloween features on the human skeleton and the deeper stories we can learn about humans from their skeletal remains.

Please see here for Peopling the Past’s statement on the discussion and display of human remains.

For many of us, the idea that somebody would amputate a finger without it being a necessity is hard to accept. We see finger amputation as a medical phenomenon. It happens accidentally, or if done deliberately, it is a surgical procedure to deal with a problem with the finger(s) in question.

However, despite what our initial gut reaction may be, amputating healthy fingers for cultural reasons has been a surprisingly common cultural practice in human history.

Cultural finger amputation is a relatively unknown practice, so not much research has been done on it. Because of this, it has been necessary to use as many different types of data as possible to investigate this phenomenon. In my research, I have used ethnographic reports by anthropologists, historical documents, archaeological material culture, and human skeletal remains to attempt to pull together a picture of the history of cultural finger amputation practices.

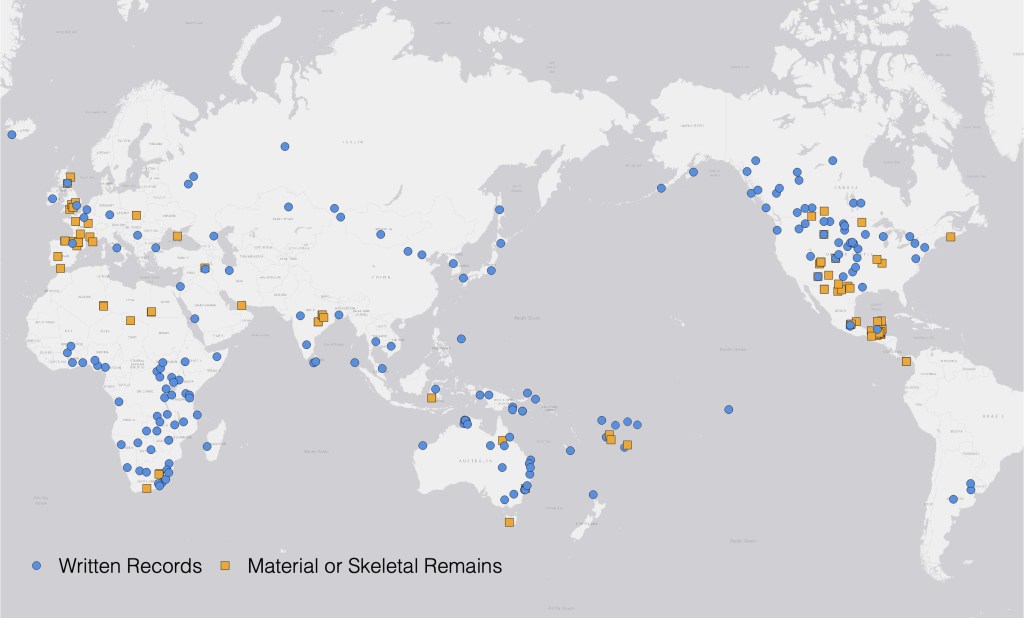

From this pieced-together information, over 200 cultures have been identified with evidence of cultural finger amputation practices (Fig 1). These societies are found worldwide and are from every inhabited continent.

Written records of these cultures’ finger amputation customs span over 2,907 years, from 883 BCE to 2024. The earliest written record from 883 BCE is from the texts of Ashurnasirpal II, the king of Assyria between 883 and 859 BCE (De Backer 2009). This document records the amputation of fingers and other body parts as a method of torture. The most recent records of finger amputation are from this year, with reports of Iranian officials using finger amputation as a punishment for theft (Iran International 2024).

Many of the written records of finger amputation customs are short and sparse—often a couple of sentences at most. Therefore, it can be difficult to fully understand cultural finger amputation customs and the people who practiced them. So, this is where skeletal remains come into play. Analyzing human remains that show evidence of finger amputation customs can give us a more nuanced view of the phenomenon and provide possible insight into the lives of the individuals who practiced cultural finger amputation.

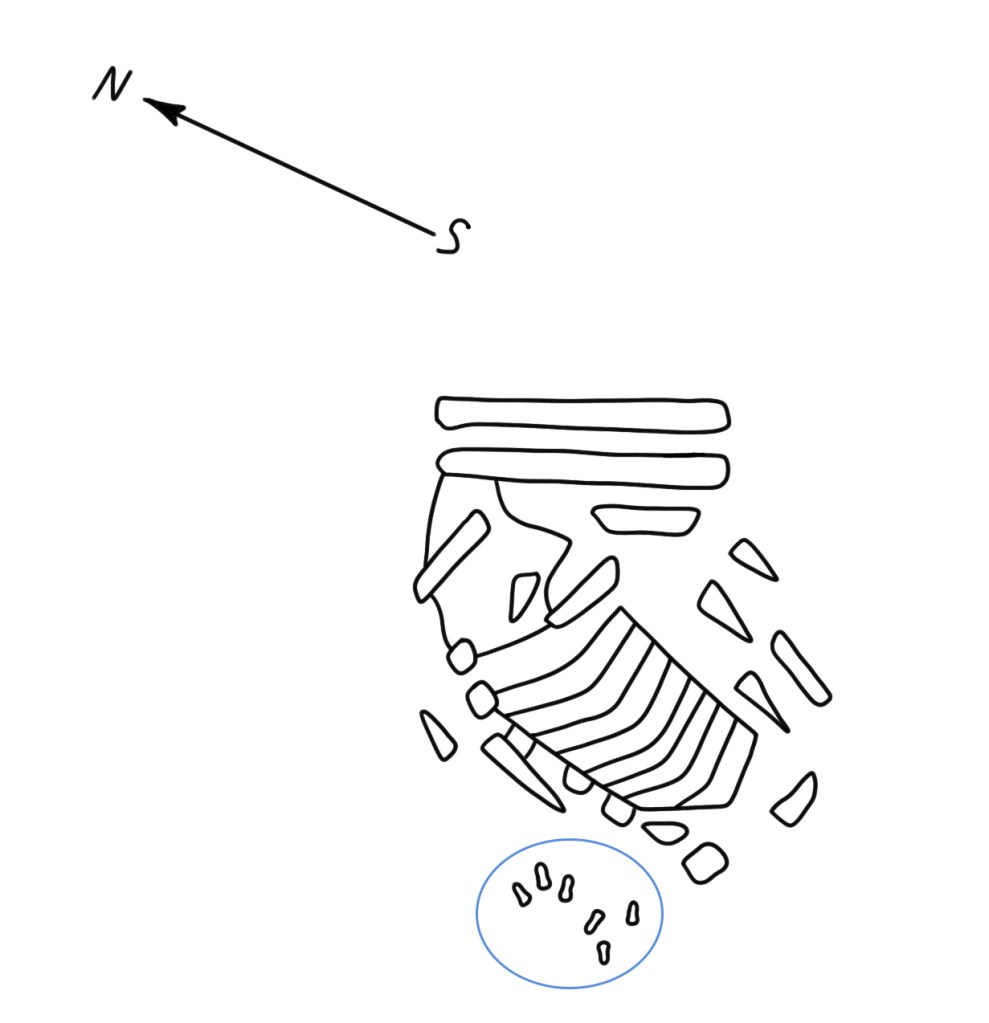

An example of skeletal remains that show evidence of cultural finger amputation comes from the site of Nokonoko on the Fijian island of Viti Levu. Here, a young infant passed away and was buried sometime between 600 and 900 CE. Near the infant was a cluster of six human finger bones (Fig 2). But these remains did not belong to the infant; rather, they were the finger bones of adults. Analysis of the finger bones showed that they were all from fingertips and likely from multiple individuals. These findings suggested that the remains were connected to a Fijian mourning ritual recorded in historical documents from the 18th and 19th centuries. To express their extreme grief and physicalize their loss, individuals would amputate a finger when a close family or community member died. This custom was so prevalent that historical documents state that it was uncommon to see an adult individual with all their fingers intact. The skeletal remains from Nokonoko demonstrate that this finger amputation practice had deep roots on the island, with an approximately 1,000 year long history.

These remains make me imagine what the people who laid this infant to rest must have been thinking and feeling. Perhaps they felt like they were leaving a piece of themselves with their loved one as they journeyed on to the afterlife. Or maybe they felt that their amputated finger would be a constant visual reminder of the connection they had with the person they had lost. While we can’t know for sure what they thought or felt at the time, we can certainly see that the skeletal remains at this site tell a story connecting finger amputation with grief, loss, and enduring love.

In addition to giving us more details about finger amputation customs, skeletal remains can also extend the history of these practices much deeper into the past. A compelling example of this can be found at the site of Murzak-Koba in the European Crimean Peninsula. At this site, a young adult woman passed away sometime between 10,000 and 7,000 years ago. When her skeletal remains were reconstructed, it was discovered that she was missing the tips of her little fingers (Fig 3). Further analysis of her finger bones showed that she had both of her little fingers amputated at the final joint when she was a teenager. The healing patterns present on the remaining bones of her little fingers were able to be used to determine the timing of the amputations. They indicated that the fingers were amputated at the same time, and the wounds were not fatal as the woman lived for quite some time after the amputations. Based on these findings, researchers have suggested that the woman had her little fingers amputated during some kind of magical or religious initiation rite.

This case makes me wish I could walk a mile in this woman’s shoes to get an idea of how she understood her amputations. Maybe the amputation of little fingers was used as a visual symbol of cultural identity. All individuals at a certain age could have undergone finger amputation to mark them as a part of the group. If so, did she feel closer to her community after this? Or perhaps the focus of the rite was more magical, whereby participants were awarded special status or protections. If this was the case, did she feel more spiritually or ritually powerful afterwards?

One of the main reasons I find cultural finger amputation fascinating is that it is an excellent example of the awe-inspiring variability of the human experience. Practices that go against our modern sensibilities today may have been deeply important customs for past cultures. Simply because we don’t understand a custom, or have never personally heard of it, does not mean it did not exist.

Bibliography

Bibikov, L. (1940). Grot Murzak-koba – novaya pozdnepaleoliticheskaya stoyanka v Krymu. Covetskaya Arkheologiya, 5, 159-178.

De Backer, F. (2009). Cruelty and military refinements. Res Antiquae, 6(1), 3–50.

Field, J. S. (2003). Archaeological Investigations of the Site of Nokonoko (2-NOK-009), District of Nokonoko, Nadrogā Province, Fiji Islands. Suva: Immigration Department of the Fiji Islands, the Fiji Museum, and the Nadrogā / Navosa Provincial Office.

Iran International (2024). Iranian Finger Amputations Continue Against International Law. https://www.iranintl.com/en/202402083948

Žirov, D. (1940). Kostyaki iz grota Murzak-koba. Covetskaya Arkheologiya, 5, 179-186.

Further Reading

McCauley, B., Maxwell, D., & Collard, M. (2018). A cross-cultural perspective on Upper Palaeolithic hand images with missing phalanges. Journal of Paleolithic Archaeology, 1, 314-333.

McCauley, B., & Collard, M. (2024). “Finger amputation in the ethnographic and archaeological records.” In: F. Manni & F. d’Errico (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology and Anthropology of Body Modification. DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780197572528.013.25

Collard, M., & McCauley, B. (2025). “Religious sacrifice in the Ice Age? Ritual finger amputation and the Gravettian hand images with incomplete fingers.” In: S. Hussain & G. Dusseldorp (eds.), Sitting on the Fence: Negotiating Archaeology, Anthropology, and Philosophy. DOI: 10.59641/uu901xg

Online Resources

Archeologický ústav AV ČR, Praha, v. v. i. (2023). Brea McCauley: Prevalence and motivations of finger amputation. https://youtu.be/2xiI9Jeeju0?si=5wlJnaFJGhU2YK2N

Brea McCauley is a PhD candidate at Simon Fraser University in Canada. Her research focuses on the history and cross-cultural variability of permanent body modification practices. She seeks to investigate why and how people modify their bodies and the earliest evidence for these practices. You can find her on X/Twitter: @brea_mccauley and learn more about her research at breamccauley.com

I know a guy who made his own finger guillotine to chop off a finger to avoid the draft for the Vietnam War. It worked.

LikeLiked by 1 person