For Halloween month, our blog posts focus on the presence of the dead among us, such as vampires, zombies, ancestors, and other types of Undead. Our authors specialize in mortuary practices across Greece, the Levant, and Mesopotamia. While the Undead are often treated superficially in popular culture, these researchers press us to think about the deeper social and spiritual meanings behind ancient beliefs and practices that attempt to manage the persistent presence of the dead amongst the living

I specialize in the analysis of human bones and burials from the ancient Mediterranean. My research bridges science and the humanities, drawing upon the methods of these very different fields to reconstruct past population dynamics and cultural practices. I’ve excavated in Pompeii and Sicily and analysed human remains from Rome, Sicily, Turkey, and the UK dating from the Bronze Age through the Byzantine period (ca. 3200 BCE to 7th century CE). The majority of my work, however, has focused on the Late Archaic/Classical Greek period (ca. 5th to 4th century BCE).

In burial contexts, past identities are reconstructed using multiple lines of evidence. Specifically, the study of human skeletal remains can reveal information about the deceased’s age at death, biological sex, stature (i.e., height), and physiological stress (e.g., diseases, injuries, periods of malnourishment), while analysis of the various components of burials—especially burial type/container, spatial orientation, body position, amounts and types of grave goods (i.e., objects buried with the dead)—can divulge additional details about the deceased’s identity and social status. Where possible, ancient literary sources are also consulted to interpret archaeological observations and provide insights into contemporary customs, traditions, and beliefs.

While analysing a Greek cemetery in Sicily, I encountered non-normative burial practices that likely reflect necrophobia. Necrophobia, or the fear of the dead, is a concept that has been present in Greek culture from the Neolithic period to the present. At the heart of this fear is the belief that the dead can reanimate and exist in a state that is neither living nor dead, but rather ‘undead.’ Scholars often refer to these beings who return from the dead as ‘revenants’ from the Latin word for ‘returning,’ revenans. Revenants are feared because it is believed that they leave their graves at night for the explicit purpose of harming the living (Figure 1).

Why, you might ask, would the dead want to harm the living? Tertullian, a Christian author living in Roman North Africa (ca. 2nd to 3rd centuries CE), tells us that the ancient Greeks believed that certain circumstances predisposed the dead to be dangerous. Under normal conditions, the soul would leave its body after death and journey to Hades, the Greek Underworld, where it would spend eternity. However, it was thought that some individuals could not transition to the Underworld in the regular fashion. These earthbound souls were ‘special’ dead who were angry with the living and capable of causing them harm.

Grouped into three categories, the special dead consisted of the aoroi, who had died prematurely or before marriage; the biaiothanatoi, who had met violent deaths in various ways (including soldiers who died in battle or persons who committed suicide); and the ataphoi, who had not received proper funerary rites or were left unburied. The ‘special’ dead were blamed for a number of inexplicable natural phenomena, from the spread of disease to destructive weather fronts. Although surviving supernatural tales tend to describe the special dead as ghosts without solid body or form, there are some notable exceptions where it seems that the apparition is in fact a revenant.

The living could protect themselves against supposed revenants. To prevent them from departing their graves, revenants must be ‘killed,’ which is usually achieved by incineration or dismemberment. Alternatively, revenants could be trapped in their graves by being tied, staked, flipped onto their stomachs, buried exceptionally deep, or pinned with rocks or other heavy objects. Although rare, the material remains of these necrophobic activities are preserved in the archaeological record, and they present modern archaeologists with the difficult task of their interpretation.

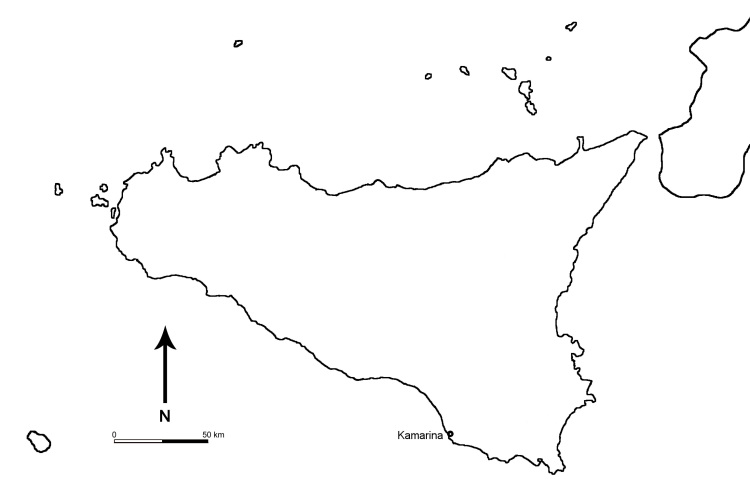

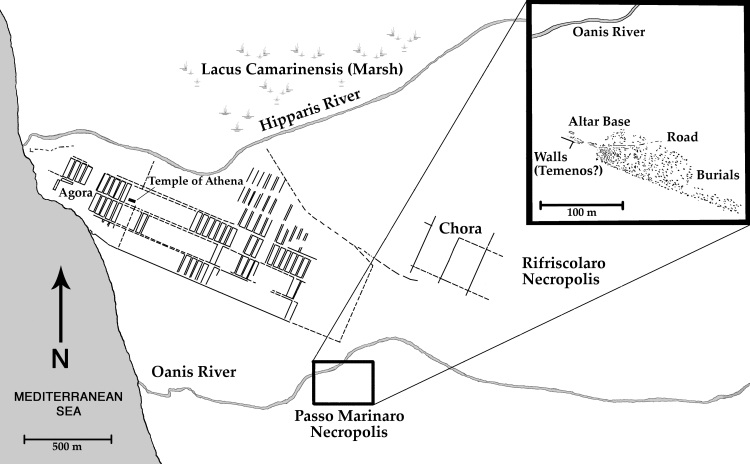

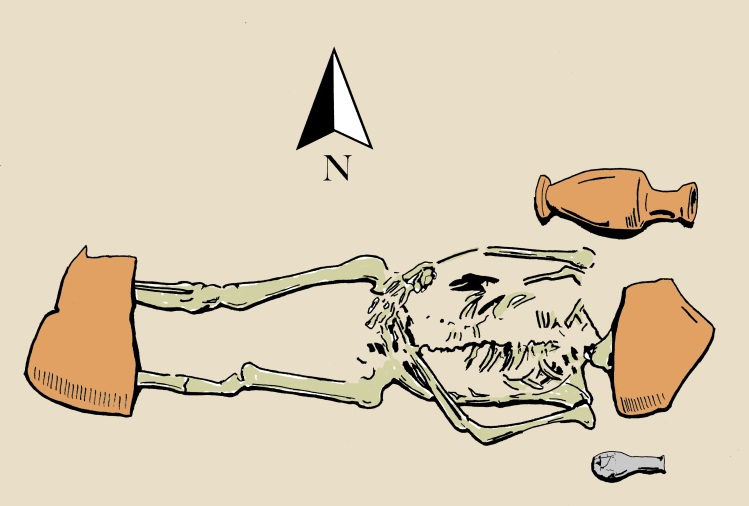

Two burials from Kamarina, a Greek colony in south-eastern Sicily (Figure 2), contain evidence of necrophobic practices. Both burials were discovered in the Classical necropolis of Passo Marinaro (Figure 3; ca. 5th to 3rd centuries BCE). The first, tomb number 653, is a simple grave without a burial container that holds an adult of indeterminate sex and stature (Figure 4). In life, this person experienced a period of serious malnutrition or illness, as evidenced by distinct horizontal lines of growth arrest that are visible on the teeth. The body is accompanied by two grave goods, an unguentarium and a lekythos. Both objects are vases that typically hold oil and are connected with Greek funerary rituals.

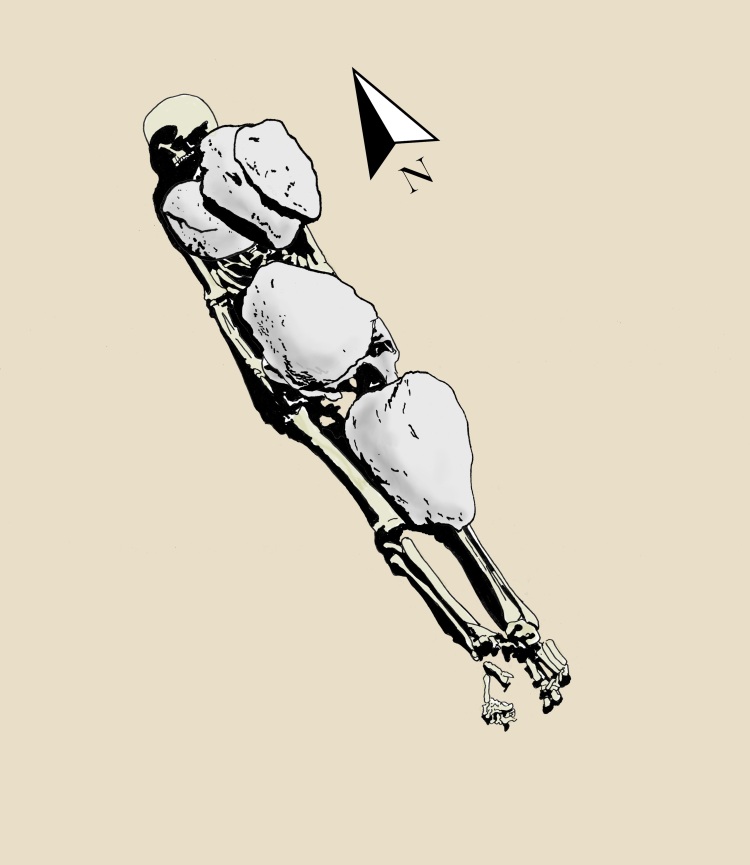

What is unusual about Tomb 653 is that the head and feet of the individual are completely covered by large amphora fragments. An amphora is a large, two-handled ceramic vessel that was typically used for storing liquids. The heavy amphora fragments found in Tomb 653 were presumably intended to pin the individual to the grave and prevent it from seeing or rising. The second burial, tomb number 693, is a simple grave without a burial container that holds a child approximately 8 to 13 years old, also of indeterminate sex and stature (Figure 5). No signs of disease are present on the child’s skeletal remains, and there are no traces of grave goods. Five large stones were placed on top of the child’s body, and like the aforementioned amphora fragments, it appears that these stones were used to trap the body in its grave. Although there are no clear indicators in either the burial contexts or the skeletal remains that would explain why the occupants of Tombs 653 and 693 were pinned in their graves, their special treatment is suggestive of necrophobic beliefs and practices.

Although necrophobia seems to be rooted in superstition and folklore, scholars like Paul Barber argue that there is a scientific basis for it. Oral and written accounts from various cultures often describe revenants as having ruddy or dark complexions, swollen and bloated bodies, flexible limbs free from rigor mortis, an ‘evil’ smell, open eyes and mouths, and blood around the lips, nose, eyes, or ears. The traditional vampire, a special class of blood-sucking revenant, also displayed these traits. Although Nosferatu, Dracula, and the characters of the Twilight saga have conditioned us to picture vampires as pale, it is likely that the vampire legend arose to explain the appearance of bodies that were flushed and bloody, presumably from nocturnal feastings on members of the community. Furthermore, all revenants also seem uncannily ‘alive’ as they tend to have warm skin, fingernails and hair that continue to grow, and are often found in positions markedly different from those in which they were buried.

These traits are all normal by-products of decomposition. As a body decays, it swells and becomes discoloured, and a blood-stained fluid seeps from the mouth and nostrils. Bloating and distention is caused by microorganisms in the abdomen that expel gases as they digest tissue. This process generates a foul stench and heat, causing the skin of the corpse to feel warm. Also, contrary to popular belief, rigor mortis is temporary. It sets in a few hours after death and dissipates within 10 to 48 hours. Thus, flexible limbs and open eyes and mouths are simply the result of relaxed muscles. Another misconception is that blood coagulates indefinitely upon death. This is true in most cases, but in instances when death is sudden and the flow of oxygen is abruptly cut-off, blood begins to clot initially, but quickly returns to a liquid state. If internal gases cause the thoracic and abdominal cavities to burst open, seemingly fresh blood spills into the burial container. Finally, the movement and release of gases can cause the body to change position, while shrinkage of the skin gives the appearance of hair and nail growth.

The horrific appearance of advanced human decomposition likely triggered foreboding and dread, prompting ancient people to rationalize these natural processes with supernatural explanations. Although we might perceive belief in revenants to be an irrational response today, we are equipped with information that was not available to the ancient Greeks. Modern advances in science, for instance, can assure us that the dead will never reanimate, whereas ancient Greeks comprehended and confronted their problems within the confines of their contemporary knowledge and worldview.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Zombie_Walk_Paris_2017_(36862101084).jpg

Today we no longer fear revenants, but we’re nevertheless captivated by the undead. Various explanations for this fascination have been offered. Some think that the undead represent what we fear most, namely the loss of our humanity, while others maintain that it is their ambiguity (they are neither alive nor dead) that terrifies and confuses us (Figure 6). Thrill-seeking tendencies might also attract us to the undead. We are drawn to things that scare us because when we are frightened in a controlled setting—one where we know we can’t be harmed—we experience a rush of adrenaline followed by a release of endorphins and dopamine that leads to a sense of euphoria. The undead are good catalysts for this response, as they strike fear on two different levels: their monstrous and supernatural qualities invoke feelings of horror because they represent a threat of unimaginable harm, while their ambiguous, near-human qualities evoke a sense of revulsion and dread. Yet, regardless of what motivates our fascination with the undead, archaeologists have a responsibility to report, interpret, and disseminate their findings objectively, without the bias of modern popular culture, in order to best educate the public on the ancient beliefs and mentalities that might be at the root of necrophobic practices.

Further Reading

Barber, P. 1998. “Forensic Pathology and the European Vampire.” In The Vampire: A Casebook, ed. A. Dundes, 109–42. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Barber, P. 1988. Vampires, Burial, and Death: Folklore and Reality. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Betsinger, T.K., A.B. Scott, and A. Tsaliki, eds. 2020. The Odd, the Unusual, and the Strange. Bioarchaeological Explorations of Atypical Burials. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

Dwyer, C. 2018. “5 Reasons We Enjoy Being Scared.” Psychology Today, 19 October 2018. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/thoughts-thinking/201810/5-reasons-we-enjoy-being-scared

Felton, D. 1999. Haunted Greece and Rome: Ghost Stories from Classical Antiquity, reprint. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Johnston, S.I. 1999. The Restless Dead. Berkeley: University of California Press.

McAndrew, F.T. 2018. “Why we Fear the Zombie Apocalypse.” Psychology Today, 11 October 2018. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/out-the-ooze/201810/why-we-fear-the-zombie-apocalypse

Sulosky Weaver, C.L. 2015a. The Bioarchaeology of Classical Kamarina: Life and Death in Greek Sicily. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

Sulosky Weaver, C.L. 2015b. “Walking Dead and Vengeful Spirits.” Popular Archaeology 19. https://popular-archaeology.com/article/walking-dead-and-vengeful-spirits/

Tsaliki, A. 2008. “Unusual Burials and Necrophobia: An Insight in the Burial Archaeology of Fear.” In Deviant Burial in the Archaeological Record, ed. E.M. Murphy, 1–16. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

Tsaliki, A. 2001. “Vampires Beyond Legend: A Bioarchaeological Approach.” In Proceedings of the XIII European Meeting of the Paleopathological Association, Chieti, Italy, 18–23 Sept. 2000, eds. M. La Verghetta and L. Capasso, 295–300. Teramo: Edigrafital.

Carrie L. Sulosky Weaver, PhD, RPA is a research affiliate of the Department of Classics at the University of Pittsburgh. She specializes in the art, architecture, and archaeology of the ancient Mediterranean world, with an emphasis on funerary art and architecture, burial practices, and the analysis of human bone. She is the author of The Bioarchaeology of Classical Kamarina: Life and Death in Greek Sicily (University Press of Florida, 2015) and the co-editor of The Ancient Art of Transformation: Case Studies from Mediterranean Contexts (Oxbow Books, 2019). Her most recent book, Marginalised Populations in the Ancient Greek World: The Bioarchaeology of the Other (Edinburgh University Press, 2022), draws upon literary, artistic, material, and biological evidence to shed new light on groups of individuals who were typically relegated to the periphery of Greek society, namely disabled, impoverished, and non-Greek peoples.